SAN DIEGO—Fibrosis affects all organ systems, but isn’t always systemic sclerosis. Experts on less common forms discussed patient presentations, diagnosis and treatment at the 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in San Diego on Nov. 6.

Retroperitoneal Fibrosis

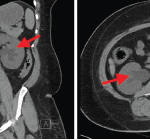

Formerly called Ormond’s disease, retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) is usually an IgG4-related disease, but has some unique characteristics, said John H. Stone, MD, MPH, director of clinical rheumatology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. New classification criteria for IgG4-related disease will be released in 2018. When IgG4 related, RPF tends to affect the area around the aorta. It may affect the submandibular gland, kidney or pancreas, too.

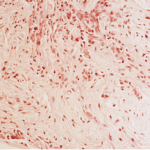

He shared biopsy results of an RPF patient with storiform fibrosis typical of IgG4 disease. “The fibrosis has a swirling pattern to it. Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is enmeshed in this fibrosis,” he said. Storiform derives from the Latin word storea or woven mat. The patient also had high eosinophils, and many of his plasma cells stained positive for IgG4.

RPF often causes obliterative phlebitis, he said. One of the patient’s veins was “completely destroyed, just trashed, by the inflammation. Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate moved in and destroyed it, so you can’t even see it without an elastin stain.”

Biopsy may be challenging as inflamed tissue is typically near the aorta and hard to reach, he said. “Often, only a small piece of tissue can be removed. You have to be careful about how you interpret what you see from a small piece of tissue. Finding overwhelming fibrosis with no footprints of the inflammation that led to that pattern is also problematic in interpretation.” In highly fibrotic tissue, stain to see if most of the plasma cells are IgG4-positive. Exclude malignancy as well, he said.

RPF is not always IgG4-related, and the association between it and other disease on this spectrum is still unclear, said Dr. Stone.1 Fewer organs are involved, often just those in the retroperitoneum. Although some patients have very high IgG4 levels, others have normal IgG4 serology.2 RPF seems to fall on the more fibrotic end of the spectrum of IgG4-related diseases, rather than the inflammatory end.

“Treatment responses are often less profound, but patients with RPF can respond and even have excellent responses. Even if their fibrosis doesn’t melt away with treatment, they can have enormous improvement in their quality of life. It’s wrong to think of these patients as having burnt-out disease that won’t respond to treatment,” he said, and finds that corticosteroids are usually very effective. Imaging may suggest fibrosis or inflammation has greatly improved with therapy in some, but not all, patients.

B cell depletion with rituximab may improve symptoms, but not reverse fibrosis on imaging, he said. “Nevertheless, patients’ lives can be improved enormously by treatment, so with either steroids and/or rituximab, we should be aggressive.”

Eosinophilic Fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) is a very rare, fibrotic disease that may mimic scleroderma. Look for key signs to make the right diagnosis, said Alisa N. Femia, MD, a dermatologist at New York University Langone Medical Center. In EF, fibrosis of the fascia can lead to contractures and functional impairment. Despite misconceptions, EF can involve the hands and feet, she said.

“Patients may come in with a scleroderma diagnosis and thickened skin, but in EF, nailfold capillary changes and Raynaud’s phenomenon are typically absent, and if Raynaud’s is present, it is not likely to be severe. In addition, in EF, the distal digits are spared,” said Dr. Femia. Other signs of EF are the groove sign, or linear furrowing along the venous structures, and pseudocellulitic appearance of the skin. In a new study of EF, 37 of 47 patients were originally misdiagnosed with such disorders as systemic sclerosis, cellulitis, deep-vein thrombosis or hypereosinophilic syndrome.3

Clinical diagnosis of EF has been made by fascial biopsy showing fibrosis of the fascia, as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells and, at times, eosinophils, but “now, we are moving more toward diagnosis with MRI, which may have the benefit of identifying an appropriate site for biopsy and helping you follow your patient’s disease course,” said Dr. Femia. EF patients may have localized plaque morphea. New research indicates EF patients may have increased expression of Th1 and Th17 cells as well.

Prednisone was effective in a 1988 study of 52 EF patients, but relapse after therapy is a concern, she said.4 Later research suggests a combination of prednisone and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, successfully treats EF. Mycophenolate mofetil in combination with steroids may be helpful for patients who are not candidates for or cannot tolerate methotrexate. “Always prescribe treatment in combination with physical therapy as soon as the patient feels well enough to do it,” said Dr. Femia.

Scleredema & Scleromyxedema

Two scleroderma mimics so rare that they have no ICD-10 codes, scleredema and scleromyxedema, have notable signs that help confirm diagnosis, said Laura K. Hummers, MD, ScM, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center in Baltimore.5

“All scleroderma mimics are not primarily fibrotic. What we see in scleredema and scleromyxedema are that these are mucinous deposition disorders. The primary problem in the skin is not necessarily collagen,” said Dr. Hummers.6 Mucin is a protein typically secreted from the epithelial cells that becomes very highly glycosylated and “gummy,” with a high molecular weight. Dermal mucin is composed of acidic glycosaminoglycans, most commonly hyaluronic acid, and produced by dermal fibroblasts.

In scleromyxedema, a patient’s hands may be hard to distinguish from those of someone with diffuse systemic sclerosis, but skin may have a papular quality that when touched feels like cobblestones, said Dr. Hummers. Scleromyxedema is systemic, rare, almost always found in adults, associated with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), and its skin/neurological form is life threatening. Patients frequently have papules on the mid-back, and/or around the glabella, forehead and ears. Papules may coalesce, and skin texture is thickened.

“One of the clinical pearls in differentiating scleromyxedema from scleroderma is this very characteristic, distinct involvement of the ear, where you can see papules behind the ear.7 Even if you can’t see them, you will feel these papules,” said Dr. Hummers. Patients may also have distinct papules on their hands, sclerodactyly, and indentation of the skin on the knuckles called the “donut sign.” Patients may have elephantine thickening of the skin around their knees called pachydermia. Scleromyxedema can rarely progress to multiple myeloma or even smoldering myeloma, said Dr. Hummers.

Scleromyxedema may have scleroderma-like features, such as dysphagia and, less often, Raynaud’s phenomenon. Patients should have normal nailfold capillaroscopy and may have inflammatory polyarthritis in small hand joints. Patients with the life-threatening dermato-neuro syndrome present with encephalopathic symptoms that are non-specific, and may begin as confusion. They may rapidly progress to seizures and coma. Patients whose skin disease is well controlled very rarely have this manifestation, she said.

Diagnosis is made with physical exam, MGUS protein on blood screening panels and a skin biopsy. Look for mucin deposition that is apparent only with special staining, and separation between collagen bundles and increased spindled fibroblasts, she said. Scleromyxedema patients nearly all respond well to intravenous immunoglobulin, but maintenance therapy is required every six to 12 weeks for life, she said. Lenalidomide or thalidomide may be used to treat the underlying MGUS, but can have side effects that affect quality of life.

Scleredema is another very rare scleroderma mimic that is either post-infectious, associated with MGUS, or associated with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Hummers.8 Skin tightening may become painful or restrictive. Patients present with a slowly progressive, doughy, non-pitting edema that typically begins around the upper back and neck, and then progresses to the upper arms, lower arms, chest, face and legs. Unlike scleroderma, it spares the fingers and feet.

Skin biopsy with special staining shows separation between collagen bundles and mucin deposition. Treat the underlying infection, MGUS or diabetes associated with scleredema. UVA-1 phototherapy may be effective for treating severe skin disease.

“Aggressive physical therapy can be helpful as well, because patients frequently complain of a limited range of motion in their shoulders and neck,” said Dr. Hummers.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta.

References

- Khosroshahi A, Carruthers MN, Stone JH, et al. Rethinking Ormond’s disease: “Idiopathic” retroperitoneal fibrosis in the era of IgG4-related disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013 Mar;92(2):82–91.

- Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Mattoo H, et al. IgG4-related disease: Clinical and laboratory features in one hundred and twenty-five patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Sep;67(9):2466–2475.

- Mazori DR, Femia AN, Vleugels RA. Eosinophilic fasciitis: An updated review on diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017 Nov;19(12):74.

- Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: Clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 May;17(4):221–231.

- Morgan ND, Hummers LK. Scleroderma mimickers. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;2(1):69–84.

- Eckes B, Wang F, Moinzadeh P, et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms in sclerosing skin diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2014;4:120.

- Blum M, Wigley FM, Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema: A case series highlighting long-term outcomes of treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Medicine (Baltimore). 2008 Jan;87(1):10-20.

- Rongioletti F, Kaiser F, Cinotti E, et al. Scleredema: A multicentre study of characteristics, comorbidities, course and therapy in 44 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Dec;29(12):2399–2404.