Since 2005, I have been directing a center for Behçet’s syndrome (BS) at New York University’s (NYU) Hospital for Joint Diseases. One question I am frequently asked is how I got interested in such a rare disease, or at least one that is rare in the U.S. I answer that family history and the Internet played big roles. My father, Hasan Yazici, MD, is also a rheumatologist. He has done a good deal of work on BS and leads one of the largest centers in the world for this disease located in Istanbul, Turkey. When I started practicing, I would get phone calls from patients, mostly from the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut area, who had been diagnosed with BS. Some—but not all—were Turkish. They would say that, while researching BS online, they had found a Dr. Yazici who had done a lot of work with BS, and they would ask if I was that same Dr. Yazici. When I told them I was his son, they would invariably say, “That’s close enough,” and make an appointment to see me.

The Internet and family connection led the first 30 or 40 patients I saw to me. By then, I was working at NYU and thought it would be a good idea to start a center to see if we could better characterize Behçet’s patients in the U.S. To date, we have seen more than 500 patients with Behçet’s, started randomized clinical trials, and worked with the National Institutes of Health to develop further studies. The center has collaborated with neurology, dermatology, and other subspecialties at NYU, and we have worked with our fellows to write abstracts and manuscripts, among other ongoing projects. It has been, and continues to be, a fulfilling experience.

Along the way, we have discovered possible differences between patients with Behçet’s in the U.S. and patients from areas where BS is more endemic. We also have found that this syndrome may not be as rare in the U.S. as was once assumed, especially in the New York area, where the ethnic and racial mix may contribute to the increased incidence of BS.

Clinical Features

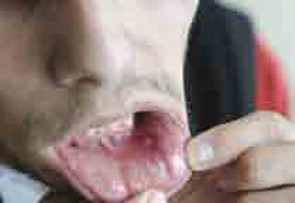

Behçet’s syndrome is a systemic vasculitis affecting the small and large vessels of both the venous and arterial systems and has an unknown etiology. It was first described by Hulusi Behçet in 1937 on the basis of three patients with a triple-symptom complex of oral aphthae, genital ulcers, and hypopyon uveitis.1 Subsequent studies showed that this entity was a multisystem disease characterized by variable clinical manifestations. Virtually all patients have recurrent oral aphthae (see Figure 1, below), with successively fewer having genital ulcers, skin lesions, arthritis, uveitis, thrombophlebitis, and gastrointestinal (GI) and central nervous system (CNS) involvement.

BS is most commonly seen in Mediterranean countries and the Far East along the ancient Silk Road, suggesting that the putative agent(s)—including several genetic factors such as human leukocyte antigen–B51 (HLA-B51)—may have spread along this path. In field surveys carried out in Turkey, the prevalence of BS was found to be between 20 and 421 cases per 100,000 adults. The disease is reported to be less frequent in the rest of the world, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 0.64 per 100,000 persons in the U.K. to 6.4 per 100,000 in Spain and 5.2 per 100,000 in the U.S. However, a more specific analysis of Turkish people living in Germany has demonstrated a distinctly high prevalence rate of 77 cases per 100,000 individuals. These findings may indicate the greater significance of genetic factors over environmental factors in the etiology.

Some manifestations of BS show regional differences. GI involvement is more frequently observed in patients from the Far East than among those from Turkey. Although a positive pathergy test is common among patients in countries and regions ranging from Turkey and the Mediterranean to Japan, it is less commonly seen in Northern European countries and the U.S. Finally, the HLA-B51 association is most pronounced among patients from the Middle and Far East.

The usual onset of the syndrome is in the third decade of life; onset of BS is uncommon among the older population (older than 50 years) and in children. Both sexes are equally affected; however, the syndrome runs a more severe disease course in men and in the young.

Mucocutaneous features are the most common presenting symptoms of the disease, although ocular, vascular, and neurological symptoms are the most serious symptoms. Almost all patients have recurrent oral ulceration. These ulcers are frequently the first observed symptom and may precede the other manifestations of BS by many years. Although aphthae are usually multiple and occur frequently in BS, they are indistinguishable from those of recurrent oral ulcers due to other causes. Genital ulcers usually occur on the scrotum in males, but they are infrequent on the shaft or on the glans penis; urethritis or dysuria is not a part of BS. In females, both major and minor labia are affected. The ulcers usually heal in two to four weeks; a large ulcer will frequently leave a scar, while a small ulcer and those on the minor labia heal without scarring. Both types of ulcers can be painful, even though painful oral ulcers are seen more frequently than genital ones.

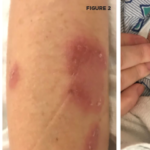

Different kinds of skin lesions are seen in approximately 80% of patients with BS. Acne-like lesions or papulo-pustular lesions are mainly of cosmetic concern because they are frequently seen at both the usual acne sites, such as the face, upper chest, and upper back, and at uncommon sites, such as the legs and arms. Nodular lesions are observed in 50% of the patients and are usually confined to lower limbs in the form of either erythema nodosum–like lesions or superficial thrombophlebitis. It can be difficult to distinguish one lesion from another with the naked eye.

The pathergy reaction is a nonspecific hyper-reactivity of the skin to trauma such as a needle prick (see Figure 2, below). A papule or pustule typically forms 24 to 48 hours after an intradermal injection of the skin with a 20-gauge needle. The pathergy positivity is relatively specific to patients with BS. Although 60% to 70% of patients in Turkey and Japan have a positive pathergy test, it is rarely observed in those with BS from Northern Europe and North America.

Eye disease is seen in half of all patients with BS but is more frequent and more severe in males and young patients. It generally occurs within three to five years of disease onset. The eye disease most commonly seen is a chronic, relapsing, bilateral uveitis involving both anterior and posterior chambers. It is a significant cause of morbidity. Anterior uveitis with intense inflammation (hypopyon) is observed in only a small fraction of patients with eye involvement and is generally associated with severe retinal disease. Isolated anterior uveitis is infrequent and conjunctivitis is rare. Recurrent attacks of eye disease result in structural changes such as synechiae and retinal scars. These events, if left untreated, lead to a loss of vision.

Joint disease is observed in half of the patients with BS in the form of arthritis or arthralgia.2 It is usually mono- or oligoarticular but can be symmetrical. Joint disease resolves in a few weeks and seldom leads to deformity or radiological erosions. The knees are most commonly involved, followed by the ankles, wrists, and elbows. Back pain is relatively rare, and controlled studies have not shown an increased sacroiliac joint involvement.

Patients with BS and arthritis also have more acne lesions. Furthermore, patients with arthritis and acne lesions have significantly higher enthesopathy scores compared with patient without acne,3 suggesting a possible link with acne-associated arthritis.

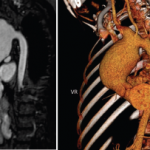

Vascular involvement can include both the venous and arterial systems. One-third of cases have thrombophlebitis of either the deep or the superficial veins, usually of the lower extremities. Despite the high frequency of thrombophlebitis, thromboembolism is rare, most likely due to the high adherence of thrombi to the diseased veins. Pulmonary arterial aneurysms are associated with a high mortality rate (See Figure 3, above right). The main symptom is hemoptysis, and patients with this symptom usually have associated thrombophlebitis.

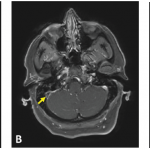

Central nervous system involvement occurs in 5% to 10% of patients and is one of the most serious manifestations of BS, causing increased rates of morbidity and mortality. Eighty percent of patients with CNS disease have parenchymal brain involvement. This mainly affects the brainstem and is manifested by pyramidal symptoms, followed by cerebellar and sensory symptoms and signs, sphincter disturbances, and behavioral changes. Nonparenchymal disease (observed in approximately 20% of those with CNS involvement), which is seen as intracranial hypertension due to dural sinus thrombosis, is manifested by headaches and papilloedema. Simultaneous involvement of the dural sinuses and brain parenchyma is unusual. Dural sinus thrombosis has a relatively benign prognosis in contrast to parenchymal involvement. Peripheral neuropathy, seen frequently in other vasculitides, is uncommon. In contrast, audiovestibular disease is increasingly recognized.

Although GI disease is frequent in up to one-third of BS patients from Japan and the U.S., it is quite rare among BS patients from Turkey. Symptoms include anorexia, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Mucosal ulceration is most commonly seen in the ileum, followed by the cecum and other parts of the colon. Ileocecal ulcers have a distinct tendency to perforate. It can difficult to differentiate inflammatory bowel disease from BS histologically. Therefore, the rarity of rectal involvement and fistulas in BS is a helpful feature.

Unlike many other systemic vasculitides, glomerulonephritis is uncommon. Amyloidosis of the AA type is seen sporadically. Epididymitis is seen approximately 5% to 10% of patients.

TABLE 1: International Study Group Diagnostic (Classification) Criteria for BS*6

Recurrent oral ulceration: Minor aphthous, major aphthous, or herpetiform ulceration observed by physician or patient recurring at least three times in a 12-month period.

Plus two of the following symptoms:

- Recurrent genital ulceration: Aphthous ulceration or scarring, observed by physician or patient.

- Eye lesions: Anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, cells in the vitreous detected with slit-lamp examination, or retinal vasculitis observed by ophthalmologist.

- Skin lesions: Erythema nodosum observed by the physician or patient, pseudofolliculitis, papulopustular lesions, or acneiform nodules observed by physician in postadolescent patients not on corticosteroid treatment.

- Pathergy: Read by physician at 24 to 48 hours.

*Findings applicable only in the absence of other clinical explanations.

Pathogenesis of Behçet’s Syndrome

Although vascular injury is quite common in BS and can involve venous and arterial vessels of all sizes, frank necrotizing vasculitis of the small and medium-sized arteries as seen in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides is infrequent in patients with BS. Similarly infrequent are giant cells and immune complex–type cutaneous venulitis. These “negative” findings make the vascular involvement in BS unique. Furthermore, there is little evidence for vasculitis in some common lesions of BS. For example, there is no evidence for vascular injury in the papulopustular lesions of the skin and scanty evidence for a frank vasculitis in the CNS lesions. Conversely, the diffuse inflammatory disease in all layers of the large veins characteristically involving substantial segments of the vessel wall, the pulmonary artery aneurysms specific to this condition, and pseudoaneurysms of the large arteries (most probably secondary to vasculitis of the vasa vasorum) are unique findings.

The genetics of BS are, at present, uncertain. No clear Mendelian pattern has emerged. In endemic areas, approximately one in 10 families have more than one family member who is affected. The most consistent genetic association has been with HLA-B51, which explains only approximately 20% of the disease heritability.

It is currently popular to group BS with autoinflammatory disorders. This categorization is debatable given that most autoinflammatory conditions (with familial Mediterranean fever being a good example) are monogenic and predominantly pediatric conditions.

Recently, it has been noted that there may be some clustering in disease expression in BS. Through a series of mainly clinical observations, two clusters have been defined. The first is the cluster of superficial vein thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis, and dural sinus thrombi; the second cluster is that of acne, arthritis, and enthesitis.4 The association of acne with arthritis and the recent observation of the pustule lesions of BS being nonsterile brings into discussion a reactive arthritis type of disease mechanism, at least for this disease cluster.5 The presence of such clusters may suggest there is more than one disease mechanism involved in this complex disorder.

There are no specific laboratory findings in BS. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level are usually moderately elevated, but these do not correlate well with disease activity. Autoantibodies such as rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are not seen.

Diagnosis and Clinical Course

The diagnosis of BS is based on the recognition of a group of clinical features because no specific signs or symptoms have been identified. In 1990, the International Study Group published a set of diagnostic (classification) criteria.6 These criteria, with a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96%, have been validated and are widely used (see Table 1, above right).

In many patients, BS goes into remission with the passage of time.7 Young or male patients usually have more severe disease with an increased frequency of both mortality and morbidity related to eye, vascular, and neurological disease compared with older or female patients. Currently, loss of useful vision is seen in fewer than 10% to 15% of the patients with eye involvement compared with three-quarters of such patients 20 to 30 years ago. Although many patients with BS, especially older females, can be managed symptomatically, the young male who presents with potentially blinding and lethal disease has to be aggressively treated, especially early in the disease course. Therefore, disease management is tailored to the type and severity of symptoms and the sex and age of the patients.

Treatment

Colchicine and low-dose corticosteroids are commonly used for minor symptoms. For eye disease, vascular, and GI involvement, azathioprine with or without a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor is usually the right treatment choice. The TNF inhibitor most commonly reported to treat BS is infliximab; in our practice adalimumab is also used, especially for patients with eye disease. Cyclosporine can also be used with azathioprine for eye disease. Azathioprine also has been shown to help with other minor manifestations of BS when colchicine and other treatments fail. Interferon-α-2a has also been used more recently for eye and CNS disease.

Recently, the European League Against Rheumatism published guidelines for managing BS.8 These provide excellent guidance for the management of disease in organ systems other than the vascular, neurological, and GI systems, simply because of the lack of controlled studies related to these pathologies. According to these recommendations, topical measures, including local steroid application, are sufficient for isolated oral and genital ulcers.

Because the main pathology of BS is inflammation of the vessel wall and the absence of thromboembolism despite the frequent thrombophlebitis, immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids and azathioprine are used instead of anticoagulants in case of thrombosis. Cyclophosphamide pulse therapy and corticosteroids are useful, especially early in the disease course, for pulmonary and peripheral arterial aneurysms. Although corticosteroids are effective for dural sinus thrombosis, it is difficult to treat parenchymal CNS disease.

The NYU Experience

In our patient cohort at NYU, we have noticed some differences when comparing these patients with cohorts from areas where BS is more endemic. Virtually all of our patients are referred with a suspected diagnosis of BS; there have been a small number who were later found to have Crohn’s disease or some other vasculitic conditions. About three-quarters of our patients are females, with about 28% having eye disease. The interesting feature of the eye involvement is that we have had no blind eyes in our cohort. This situation can be due to referral bias or to some other factor, but is interesting to note. We looked at our patients and divided them into two groups—patients of Northern European descent and patients from areas where BS is endemic. Roughly two-thirds of our patients are of Northern European descent and one-third from more endemic areas. The Northern European group had significantly more GI disease and more female patients. These findings are consistent with data from other groups, indicating that there are geographic differences not only in disease manifestations but also possibly in disease severity, as evidenced by the absence of blindness in our cohort.9

BS outcomes have improved over the last 20 years, thanks to earlier and more aggressive treatment strategies. However, vascular involvement and CNS problems are areas that still need better treatments. We hope our center will play an important role in helping BS patients, not only in the U.S. but also across the globe.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the research assistants and other personnel who have helped me over the years in getting our center started; it would not have been possible without them.

Dr. Yazici is Assistant Professor of Medicine at NYU School of Medicine and director of the Seligman Center for Advanced Therapeutics and Behçet’s Syndrome Evaluation, Treatment and Research Center.

Disclosures

Dr. Yazici is a consultant/speaker for Bristol–Myers Squibb, Celgene, Centocor, Genentech, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

References

- Behçet H. Uber rezidivierende, aphthose, dürch ein Virus verursachte Geshwure am Munde, am Auge und an den Genitalien. Dematologische Wochenschrift 1937;36:1152-1157.

- Moses Alder N, Fisher M, Yazici Y. Behçet’s syndrome patients have high levels of functional disability, fatigue and pain as measured by a Multi-dimensional Health Assessment Questionnaire (MDHAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(4 Suppl 50):110-113.

- Hatemi G, Fresko I, Tascilar K, et al. Enthesopathy is increased among Behçet’s syndrome patients with acne and arthritis: An ultrasonographic study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1539-1545.

- Tunc R, Saip S, Siva A, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis is associated with major vessel disease in Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1693-1694.

- Hatemi G, Bahar H, Uysal S, et al. The pustular skin lesions in Behçet’s syndrome are not sterile. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1450-1452.

- International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080.

- Kural-Seyahi E, Fresko I, Seyahi N, et al. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: A 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:60-76.

- Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s disease: Report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1656-1662.

- Yazici Y, Schimmel E, Swearingen C. Behçet’s syndrome in the US: Clinical characteristics, treatment and ethnic/racial differences in manifestation in 347 patients with BS. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, presented at 2009 ACR meeting.