NEW YORK (Reuters Health)—Data from a genetic association study suggest that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be divided into a three-group continuum, rather than the current division between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

“The current clinical classifications of IBD, while important and useful, are a simplification of the true biological variation of this disease,” Dr. Jeffrey C. Barrett from Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, U.K., told Reuters Health by email. “Ultimately, if we improve this classification system, we’ll hopefully have more successful trials for new medicines and better ability to give the right drug to the right patient.”

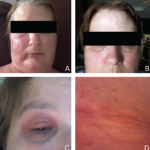

At least 163 susceptibility loci related to IBD have been identified so far, with most conferring risk of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, Dr. Barrett and colleagues note in The Lancet, online Oct. 19. Molecular studies have suggested that ileal and colonic Crohn’s disease are distinct entities because of specific variants in NOD2 (in small bowel disease) and HLA alleles (in colonic disease).

The researchers used genetic risk scores from nearly 30,000 IBD patients to study genetic heterogeneity underlying the natural history of IBD. Three genetic loci achieved genome-wide significance: 3p21 (MST1), NOD2, and the major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

As in earlier studies, NOD2 was strongly associated with Crohn’s disease location, but adjustment for the other phenotypes found that the association of NOD2 with IBD behavior was driven almost entirely by its correlation with location and age at diagnosis.

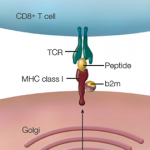

Several human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles correlated with IBD susceptibility, location, and extent: HLA-DRB1*07:01 was the strongest signal for colonic disease and the strongest shared risk allele for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; rs77005575 was associated with Crohn’s disease behavior; HLA-B*08 was the top signal for the extent of ulcerative colitis; and HLA-DRB1*13:01 was the top signal for age at diagnosis of ulcerative colitis.

The genetic risk score strongly favored a model in which colonic Crohn’s disease is intermediate between ileal Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis over the model that grouped both Crohn’s disease subphenotypes as a single category.

“Despite the fact that we’ve found 200 regions of the genome associated with IBD risk, we only found three that were individually strongly associated with clinical phenotype,” Dr. Barrett said. “To me that suggests that the way in which we clinically stratify patients is imperfectly capturing the true underlying biology of their disease. We hope that the genetics results in our study will help to improve that stratification in the future.”

“For personalized treatments we need to understand which cells are affected in particular patients, and how they’ve gone wrong in maintaining the balance between healthy and exaggerated inflammation,” Dr. Barrett added.

Dr. Joana Torres from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., who coauthored a related editorial, told Reuters Health by email, “The quest to identify biomarkers that can allow clinicians to predict disease course and disease complications is gaining increasing importance. It is also increasingly obvious that no single biomarker will be able to perform such a task in a complex disease as IBD.”

“Likely, in the future, algorithms that incorporate specific genetic risk alleles with other markers (e.g., antimicrobial markers, specific proteomic signature, microRNAs, etc.) will be used to predict complications, response to specific therapies, risk for surgery, etc., allowing true precision medicine to become real in IBD,” Dr. Torres said.

“Genetics alone are not useful in predicting disease course, disease complications, or behavior,” she concluded. “Other avenues of research that integrate genetic with non-genetic factors (such as the microbiome, early life environmental exposures, etc.) need to be developed if any light is to be shed onto the complex pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease.”