There must be another reason for these discrepancies—and there is. Drive a car for 50,000 miles and the tires will be worn out. We can also assume that, if you live to be 80 or 90, some of your cartilage will wear out too, so age certainly is a factor. But driving a car just 10,000 miles with tires in poor alignment can create much greater wear than driving 50,000 miles with properly aligned tires. Malalignment is exactly what happens in OA.

OA of a particular weight-bearing joint develops because improper alignment (like a flattened foot or a longer leg) causes increased friction and pressure on a localized area of that joint, subsequently causing its deterioration. The greater the malalignment and the more active a patient is, the earlier deterioration will be seen. The combination of malalignment and activity is one of the reasons we see knee pain in young athletes. This concept of abnormal alignment is critically important in preventing and eliminating the symptoms of OA. I believe malalignment is the predisposing factor of this disease, and the missing link between its real cause and proper treatment.

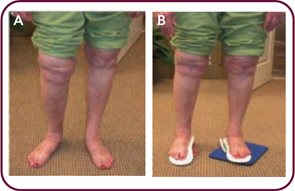

Second only to age, weight is consistently noted as a major cause of OA. The more weight you carry, the more stress you place on weight-bearing joints but, again, a logical fallacy may be at work here. There are many significantly overweight people without joint problems, and there are others who weigh far less than average but have arthritic joints. As with older people, many overweight individuals with arthritis have one knee or hip that hurts more than another, and sometimes only one joint is ever involved. Is all their weight on one side? Why, if the overweight issue is resolved and an arthritic joint replaced, does that new joint sometimes go bad, too? Think again of the automobile analogy: putting a new tire on a car with a bent frame does nothing to improve the frame. In fact, with joint replacement surgery for knees and hips, some patients end up with worse alignment because a major complication of this surgery is an even greater leg length discrepancy, which causes additional stress on the joint replaced, as well as on other weight-bearing joints (see Figure 1, p. 33).

Like age, weight certainly is a factor in disease development. Additional weight can cause a joint to deteriorate because it causes increased friction and pressure, and we know that losing weight is helpful. However, friction and pressure that are concentrated in a localized area due to poor alignment can cause joint deterioration to occur much faster, and much more severely, than additional weight that is evenly dispersed. Additional weight becomes much more important when the added load is placed on an uneven (i.e., improperly aligned) structure, such as a person with unequal leg lengths. In 2007, Kan et al, reported finding a “higher risk of developing OA in obese patients with poorly aligned knees than with normal alignment.”3 Even a Rolls Royce doesn’t ride well with a 20-inch wheel on one side and an 18-inch wheel on the other.

Role of Malalignment in OA Pathogenesis

I am not a research scientist, but I have the utmost respect for those who are. I’m a clinician who, for the last forty years, has been treating patients, reading the literature, and simply observing how people function every day. My perspective is different because I have subspecialized in a number of seemingly unrelated areas of medicine. In each instance, the thing I was interested in least—biomechanics—was the common thread that haunted me. Yet nowhere have I found the importance of controlling pathomechanics more applicable than in rheumatology.