In an article on osteoarthritis (OA), Hunter et al stated that current physician guidelines by the ACR for the management of OA of the knee and hip are outdated and incomplete, with current clinical management often limited to analgesic medications—many of which now are under scrutiny because of safety concerns—and ‘cautious waiting.’ ”1 I couldn’t agree more. Frankly, it was with great reluctance that I changed my thinking on this subject many years ago. This change has greatly benefited my patients, and I am convinced that it can benefit yours. Now that there is enough “hard” data to support the premise that joint malalignment is a key cause of OA (see “Research Overview,” p. 33), I humbly submit that, for a few moments, you, too, think “outside of the box,” and see if this approach makes as much sense to you as it does to me.

Let’s face it, what we’re doing isn’t working. Although medications may temporarily alleviate the symptoms of OA, and joint replacement surgery has helped many to remain active, we’re not doing very much to stop the etiology or the progression of this “rising epidemic.”1

The Typical Scenario

I believe that the treatment options offered to someone with OA of the knee leave something to be desired. When joint pain becomes more than incidental, and medication no longer works as well or for as long as it used to, the patient will consult a rheumatologist or an orthopedic surgeon. If the symptoms of pain are not yet severe, the patient is often told to, “come back when it’s bad enough” and have the joint replaced, as nearly 600,000 patients do each year.2

At this point, if surgery is not performed, many patients are often left hanging, continuing to take their pain pills and trying to stay active until they can no longer tolerate their symptoms. Certainly, there should be a better alternative than “cautious waiting” until a joint replacement is needed, at which point the process may begin all over again. For some patients, the new prosthetic joint may loosen or wear out and need replacement too. This unfortunate scenario takes place every day in physicians’ offices all over the world. As you know, even if considered successful, a knee replacement will not generally be a “normal knee” with a full range of motion. A surgeon may be able to get a patient on the road again by putting a “run-flat” tire on their car, but those temporary tires are not as safe, and they will never give the comfortable ride or performance that the original set did.

If one of the tires on your car were wearing out faster than the others, would it make sense to continue driving on it until it wore out completely, replace it, and begin the process again? You would certainly want to find out why the wear is happening so quickly and fix the cause. And, if your mechanic didn’t have the answer, you would find one who did. However, people who have OA in weight-bearing joints must accept this approach as the norm, because in medicine at present, there is no mechanic offering a different option.

I was originally trained as a foot and ankle surgeon. I feel that replacing an artificial joint without understanding the mechanisms of joint deterioration is incomplete at best—as incomplete and unacceptable as thinking that the only alternative to osteoarthritis is to medicate its associated symptoms. My background in surgery and experience in prolonging joint replacements led to my initial change in thinking regarding the true etiology of OA of the weight-bearing joints. Let’s look at the two most common factors identified with OA: age and weight.

Age and Weight

The one single factor consistently associated with the cause of OA is age. Like gray hair and wrinkles, OA is something you can count on having if you live long enough. The eventual development of OA almost seems inevitable because, given enough time, friction can destroy almost anything. Assuming that age is the primary cause of arthritis, however, is like assuming that age causes heart disease because many older people have heart problems. You didn’t get heart disease from the potato chip you ate when you were 73 years old. There is a logical error here that involves something we are all familiar with: the difference between a correlation and a cause. For both heart disease and OA, I believe the pathological process actually begins in childhood, taking years before symptoms develop and confirming diagnostic tests are available. At that point in OA, extensive joint damage may have already occurred.

In almost all instances of OA of the knees or hips, one joint is symptomatic first—sometimes it’s the only joint ever involved. Because we know that one knee or hip joint isn’t younger than the other, this situation raises some important questions. If age is the primary cause of OA, why do some 90-year-olds have no arthritis in their knees, while some individuals who much younger have severe arthritic changes in these joints?

There must be another reason for these discrepancies—and there is. Drive a car for 50,000 miles and the tires will be worn out. We can also assume that, if you live to be 80 or 90, some of your cartilage will wear out too, so age certainly is a factor. But driving a car just 10,000 miles with tires in poor alignment can create much greater wear than driving 50,000 miles with properly aligned tires. Malalignment is exactly what happens in OA.

OA of a particular weight-bearing joint develops because improper alignment (like a flattened foot or a longer leg) causes increased friction and pressure on a localized area of that joint, subsequently causing its deterioration. The greater the malalignment and the more active a patient is, the earlier deterioration will be seen. The combination of malalignment and activity is one of the reasons we see knee pain in young athletes. This concept of abnormal alignment is critically important in preventing and eliminating the symptoms of OA. I believe malalignment is the predisposing factor of this disease, and the missing link between its real cause and proper treatment.

Second only to age, weight is consistently noted as a major cause of OA. The more weight you carry, the more stress you place on weight-bearing joints but, again, a logical fallacy may be at work here. There are many significantly overweight people without joint problems, and there are others who weigh far less than average but have arthritic joints. As with older people, many overweight individuals with arthritis have one knee or hip that hurts more than another, and sometimes only one joint is ever involved. Is all their weight on one side? Why, if the overweight issue is resolved and an arthritic joint replaced, does that new joint sometimes go bad, too? Think again of the automobile analogy: putting a new tire on a car with a bent frame does nothing to improve the frame. In fact, with joint replacement surgery for knees and hips, some patients end up with worse alignment because a major complication of this surgery is an even greater leg length discrepancy, which causes additional stress on the joint replaced, as well as on other weight-bearing joints (see Figure 1, p. 33).

Like age, weight certainly is a factor in disease development. Additional weight can cause a joint to deteriorate because it causes increased friction and pressure, and we know that losing weight is helpful. However, friction and pressure that are concentrated in a localized area due to poor alignment can cause joint deterioration to occur much faster, and much more severely, than additional weight that is evenly dispersed. Additional weight becomes much more important when the added load is placed on an uneven (i.e., improperly aligned) structure, such as a person with unequal leg lengths. In 2007, Kan et al, reported finding a “higher risk of developing OA in obese patients with poorly aligned knees than with normal alignment.”3 Even a Rolls Royce doesn’t ride well with a 20-inch wheel on one side and an 18-inch wheel on the other.

Role of Malalignment in OA Pathogenesis

I am not a research scientist, but I have the utmost respect for those who are. I’m a clinician who, for the last forty years, has been treating patients, reading the literature, and simply observing how people function every day. My perspective is different because I have subspecialized in a number of seemingly unrelated areas of medicine. In each instance, the thing I was interested in least—biomechanics—was the common thread that haunted me. Yet nowhere have I found the importance of controlling pathomechanics more applicable than in rheumatology.

No weight-bearing joint problem is independent. Rather, joints function together in an interdependent way as an integral part of our kinetic chain, the alignment of which ultimately determines our ability to function asymptomatically. Structural alignment always has an important role in rheumatology for two reasons. First, no one is born structurally perfect—even our right and left sides are not identical mirror images of each other. Any degree of malalignment will (like the tires on a car) result in premature, abnormal joint wear. Because none of us are perfect structurally, joint-deteriorating imperfections are present constantly, in every patient, until corrected.

Second, OA—like rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other diseases that can affect the weight-bearing joints—can alter gait patterns, which can result in deteriorating frictional forces on other joints that may not yet be symptomatic. Pathomechanics is always a factor in the arthritic conditions we’re treating; sometimes, as in the case of OA, it can be the primary factor. I would assert that any treatment that does not address pathomechanics is incomplete at best.

The foundation is critically important to any structure, and our bodies are no different. To help patients with OA of the weight-bearing joints function better, the first place to look is their feet. We are all like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, meant to stand erect but cockeyed since birth. The way such a structure is fixed is not by taking wedges out or splinting its middle, but by shoring up its foundation. When treating OA patients, have them stand up and make sure that their feet are optimally positioned (subtalar neutral) under their legs. In most cases, if this is accomplished, you will see an immediate decrease in symptoms and increase in function. My experience is that the more accurately this is done, the better the results.

It is interesting that most examinations for painful knees and hips are done sitting or supine, even though this is not how these patients will function. To truly evaluate OA patients, more attention needs to be directed to seeing how they stand and walk. Isn’t that why we prefer in vivo studies to those in the test tube? We want to understand how things work in a real world environment, not an artificial one.

We know that motion is an essential part of maintaining a healthy joint. The “use it or lose it” philosophy seems quite logical. But using a joint in poor alignment is also destructive—pitcher’s elbow is a prime example. Observing how a patient’s joints function when bearing weight is essential to evaluation.

Most people pronate excessively. This motion occurs at the subtalar joint, which, because of its important influence on the structures above, I consider the “structural core” of the human body. Besides the foot rolling in and flattening, this triplane motion causes abduction and eversion. These motions result in the foot (our foundation) dislocating from underneath the body. The profound effect this motion has on other joints cannot be overemphasized, and leads me to make a simplistic statement, knowing full well that it is destined for skepticism: The major cause of OA of the weight-bearing joints is excessive pronation at the subtalar joint, which causes abnormal alignment of the knees, hips, and back, resulting in the increased friction that subsequently causes joint deterioration. I advance this proposition understanding that more proximal deformities, like scoliosis, can cause lower extremity problems as well.

To better appreciate the structural issues, stand up and pronate your right foot. Notice how much this pronation (an almost universal problem) causes your knee to internally rotate. Take a few steps around the room and begin to imagine what a destructive force this would have on your knee over the course of a lifetime. If pronation or a flattening of your foot had always been a problem for you, would it be accurate to say that, at age 70 years, the cause of your OA was age, and perhaps excessive weight? Or, would it be more accurate to say that your pathomechanics was the primary cause of your problem, age and weight being important secondary factors? Next, stand in front of a mirror and, while leaning slightly on the outsides of your feet (somewhat supinated), do a few simple squats. You should notice that your knees are tracking straight and not internally rotated. Repeat this maneuver while trying to maximally pronate your feet and you should see and feel the increased tension and stress on the insides of your knees. You will also notice less force/power.

It is important to evaluate the difference in the position of a patient’s feet, knees, and hips on and off weight bearing, because testing in these positions can show the deforming forces caused by the effects of malalignment and gravity and demonstrate how the patient will actually function. As an example of another evaluation, sit in a chair, barefoot and in shorts, with your knees at right angles to your hips and your feet lightly resting on the ground. Supinate your feet slightly (subtalar neutral), so that they are aligned directly under your knees. Now stand up and let your feet assume their normal position. In most instances, some pronation will occur, as seen by a flattening of the feet, accompanied by internal rotation of the knees. I consider that any change in this positioning between sitting (making sure your foot is in subtalar neutral) and full weight bearing is pathological and will cause deterioration of the weight-bearing joints.

Try this test on one of your patients to really appreciate the effect of foot position on a symptomatic knee. Most people with arthritis of the knees will also have some pain when doing the simple squat test I mentioned above. However, in many instances, when this test is repeated with some small wedges (like simple doorstops) under the forefoot and rear foot, (so that the patient is more supinated and his or her knees are more vertically aligned), the patient can usually squat easier and with less pain. The reduction in symptoms occurs in many instances because you are now allowing the joint to function on some remaining cartilage laterally. These results are improved further when a small lift (1/4 inch or more) is placed under a short leg.

I fully appreciate that we are all under severe time constraints with our patients. However, I believe that, in most cases, improvements (sometimes dramatic and immediate) can be made by incorporating brief structural evaluations into routine examinations. You will also find less need for medications and surgery. The goal of this article is not to make you a specialist in biomechanics—I’m certainly not. Rather, I would like to:

- Help you appreciate the important role of pathomechanics in arthritis of the weight-bearing joints;

- Share some simple ways to evaluate structural abnormalities and the need for correction;

- Suggest a basic treatment plan; and

- Help you determine the effectiveness of therapy.

Steps for a Therapeutic Approach to Pathomechanics

- Accept the premise. As I mentioned at the onset, the first step in implementing this treatment plan is to appreciate fully the role of patholmechanics in OA—and there is much supportive data (see “Research Overview,” p. 33).

- Identify the presence of structural abnormalities. While a patient is standing, notice if one arm is longer or one shoulder is higher. See if one knee is more flexed, one hip seems higher, or one foot is flatter than the other. Watch your patients walk. Ask them to squat and see if their knee (or knees) internally rotates. Most importantly, while they are seated, place their feet (in subtalar neutral) directly under their knees and notice the difference when they stand up, as described above. The critical care element here is to hold this optimal, subtalar neutral, non–weight bearing foot position, because this will dramatically affect all weight-bearing joints.

- Make a good physical therapist part of the team. Focus must be redirected to finding and correcting the specific structural abnormalities that are the real causes of OA (e.g., leg length differences). Once the joints are aligned, range of motion and strength and conditioning exercises, as well as braces and other therapeutic modalities, will be far more effective.

- Limit patient weight-bearing activity. Doing this initially can be quite helpful because using a joint in poor alignment can far outweigh the positive benefits of exercise. Once alignment is accomplished, activities can often be resumed, often with far more effectiveness.

- Help patients lose excessive weight. Weight is an important secondary factor in OA.

- Prescribe custom foot orthotics. Orthotic is a very broad, generic term that implies “something” that is being used to support the arch. Much confusion exists about terminology and classifications. Strictly speaking, the more correct term is orthosis, from the Greek for “straight, upright, or correct.” The implication of the derivation is the most important thing: your patients should be standing straight and upright when on their devices, and not be as pronated as they are without them.

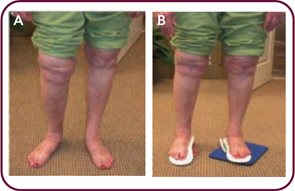

Simply having foot orthotics is meaningless. As with a set of prescription eyeglasses, the precision with which orthotic corrections are made is directly related to decreasing symptoms and improving function. Once you begin looking at correction, you will see that, many times, patients have very little correction at all. One of the biggest reasons for this is improper casting technique. There is usually a significant difference in a patient’s foot when on and off weight bearing (see Figure 2, below). In my opinion, impressions that are taken with the patient standing can only capture the foot in its pathological, usually maximally pronated position. I believe that a device made from such an impression is far less effective than one produced from a non–weight bearing cast.

Because of the implications of this approach, achieving optimal correction should be given the same due diligence used to prescribe and monitor medications. To utilize orthotics optimally, I recommend that you find an experienced podiatrist or other professional to make these devices and insist on optimal correction (subtalar neutral). Once the devices are made, you should evaluate your patients standing barefoot on and off the devices and, if ideal correction is not achieved, ask to have the devices adjusted. I often do this a number of times with the devices on my own patients, and the results are well worth it.

New OA Guidelines

The ACR is currently finalizing updated recommendations for the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management of osteoarthritis of the hip, knee, and hand. It is anticipated the recommendations will be published in Arthritis Care & Research by late summer.

Therapeutic Effect of Controlling Malaglignment

Pathomechanics is a major factor in the etiology and progression of OA of the weight bearing joints. My feeling is that the focal point of this pathological process is excessive pronation at the subtalar joint. By optimally controlling the function of this important joint, it would seem that better alignment would be achieved and subsequent signs and symptoms reduced. This scenario would also imply that, with early disease, prevention is possible, while in advanced cases, results would probably not be as effective. Also, with proper alignment, joint replacement surgery may be prevented or delayed, and the life of replacement joints might be extended. All of this has been my experience.

While physical therapy, exercises, braces, and other modalities can be helpful, I have found nothing more powerful or rapidly effective as custom foot inserts. Structural alignment must be the first step if optimal results are to be achieved.

Much of what others and I have learned about controlling symptomatic pathomechanics of the weight-bearing joints comes from treating runners. I experienced this firsthand when I developed a stress fracture in my fibula while training for a race in California. It was 1972, and I was doing my residency there; at the time it was the running Mecca of the world. The custom foot orthotics I was given had an impressive effect in both eliminating my symptoms and expanding my thinking. What I learned, I applied to treating conditions like runner’s knee, IT band syndrome, and other more proximal conditions by controlling excessive subtalar joint pronation. Many others have experienced similar impressive results. Williams et al showed significant differences in tibial torsion and knee abduction in symptomatic runners with orthotics.4 MacLean et al demonstrated improved knee function even in asymptomatic runners.5 A study on runners done at the Human Performance Laboratory at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, showed that orthotics decreased excessive pronation, increased vertical loading, and external knee rotation.6

Similarly, improved function has been demonstrated by using foot orthotics in those with knee OA.7,8 Gross and Foxworth’s literature review (and personal experiences) showed a reduction in patellofemoral pain when abnormal pronation and other malalignment issues are corrected.9 A far more extensive literature review was conducted by Marks and Penton, who found strong evidence for a reduction in symptoms and improvement in biomechanics in those with knee OA.10 Krohn demonstrated improvement in those with knee OA by combining foot orthotics with knee bracing.11 When foot orthotics were added to other treatment modalities, 76.5% of Saxena and Haddad’s patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome had a reduction in symptoms, while Rubin and Menz showed that, although greater reduction was achieved in less severe cases, at six weeks, all subjects with knee OA had demonstrated some reduction in symptoms.12,13 Johnston and Gross’s study showed significant improvements in patellofemoral pain syndrome cases in pain and stiffness just two weeks after treatment with custom foot inserts.14 Keating et al found, as I have, that sometimes even in severe cases of knee OA, where there was complete loss of joint space and bony erosion, some patients showed improvement in symptoms.15

These improvements are not limited to just OA knee cases. Dananberg and Guiliano showed that patients treated with custom foot inserts experienced more than twice the alleviation of chronic low back pain for twice as long when compared with traditional modes of therapy.16 Children with juvenile RA have been shown to have significant improvements in pain, level of disability, and function with custom foot inserts.17 The efficacy of inserts in adult RA and other conditions, such as hemophilia, has also been shown.18-26 Beyond improvements in mechanics and symptoms, custom foot orthotics can decrease the need for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other medications. Brouwer et al found that even strapping the subtalar joint to prevent excessive pronation cause significant improvements in OA knee pain during bed rest and ambulation.27 Gélis et al showed that those treated with foot inserts for knee OA consumed fewer NSAIDs than the placebo group for up to two years.28

Despite the help we offer patients by alleviating symptoms with medication and joint replacement, we have not been able to prevent or stop the progression of OA. By learning to incorporate a basic, structural evaluation into current examinations and to recognize and correct significant pathomechanic problems, I believe that we can begin to offer a treatment program that addresses the true etiology of OA. And when you consider the powerful indirect effects treating OA can have on diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and the other medical problems plaguing our society, you see that improving function is critically important.

Current supportive data, coupled with the innocuous, inexpensive, generally beneficial effect of optimally corrected custom foot inserts, necessitates that this adjunctive therapy become standardized. Indeed, it is time we changed our thinking.

Dr. Pack is a physician at MCG Medical Associates in Greensboro, Ga., and a founding fellow of the ACR.

References

- Hunter DJ, Lo GH. The Management of osteoarthritis: An overview and call to appropriate conservative treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:689-671.

- Total knee replacements increase mobility and motor skills in older patients. Available at www.physorg.com/news165168783.html. Published June 25, 2009. Accessed February 11, 2010.

- Khan FA, Koff MF, Noiseux NO, et al. Effect of local alignment on compartmental patterns of knee osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1961-1969.

- Williams DS 3rd, McClay Davis I, Baitch SP. Effect of inverted orthoses on lower-extremity mechanics in runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:2060-2068.

- MacLean C, Davis IM, Hamill J. Influence of a custom foot orthotic intervention on lower extremity dynamics in healthy runners. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006; 21:623-630.

- Mündermann A, Nigg BM, Humble RN, Stefanyshyn DJ. Foot orthotics affect lower extremity kinematics and kinetics during running. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003;18:254-262.

- Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Goggins J, Merriman GJ, Kaplan RJ, Felson DT. Effectiveness of a lateral-wedge insole on knee varus torque in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:889-893.

- Schmalz T, Blumentritt S, Drewitz H, Freslier M. The influence of sole wedges on frontal plane knee kinetics, in isolation and in combination with representative rigid and semi-rigid ankle-foot-orthoses. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2006;21:631-639.

- Gross MT, Foxworth JL. The role of foot orthoses as an intervention for patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:661-670.

- Marks R, Penton L. Are foot orthotics efficacious for treating painful medial compartment knee osteoarthritis? A review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:49-57.

- Krohn K. Footwear alterations and bracing as treatments for knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:653-656.

- Saxena A, Haddad J. The effect of foot orthoses on patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93:264-271.

- Rubin R, Menz HB. Use of laterally wedged custom foot orthoses to reduce pain associated with medial knee osteoarthritis: A preliminary investigation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:347-352.

- Johnston LB, Gross MT. Effects of foot orthoses on quality of life for individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:440-448.

- Keating EM, Faris PM, Ritter MA, Kane J. Use of lateral heel and sole wedges in the treatment of medial osteoarthritis of the knee. Orthop Rev. 1993;22:921-924.

- Dananberg HJ, Guiliano M. Chronic low-back pain and its response to custom-made foot orthoses. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89:109-117.

- Powell M, Seid M, Szer IS. Efficacy of custom foot orthotics in improving pain and functional status in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A randomized trial. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:943-950.

- de P Magalhaes E, Davitt M, Filho DJ, Battistella LR, Bertolo MB. The effect of foot orthoses in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:449-453.

- Woodburn J, Helliwell PS, Barker S. Changes in 3D joint kinematics support the continuous use of orthoses in the management of painful rearfoot deformity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003; 30:2356-2364.

- Woodburn J, Barker S, Helliwell PS. A randomized controlled trial of foot orthoses in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002; 29:1377-1383.

- Li CY, Imaishi K, Shiba N, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of foot pressure and loading force during gait in rheumatoid arthritic patients with and without foot orthosis. Kurume Med J. 2000;47:211-217.

- Chalmers AC, Busby C, Goyert J, Porter B, Schulzer M. Metatarsalgia and rheumatoid arthritis—a randomized, single blind, sequential trial comparing 2 types of foot orthoses and supportive shoes. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1643-1647.

- Hodge MC, Bach TM, Carter GM. Novel Award First Prize Paper. Orthotic management of plantar pressure and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1999;14:567-575.

- Clark H, Rome K, Plant M, O’Hare K, Gray J. A critical review of foot orthoses in the rheumatoid arthritic foot. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:139-145.

- Mejjad O, Vittecoq O, Pouplin S, et al. Foot orthotics decrease pain but do not improve gait in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:542-545.

- Slattery M, Tinley P. The efficacy of functional foot orthoses in the control of pain in ankle joint disintegration in hemophilia. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:240-244.

- Brouwer RW, Jakma TS, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (1):CD004020.

- Gélis A, Coudeyre E, Aboukrat P, Cros P, Hérisson C, Pélissier J. Feet insoles and knee osteoarthritis: Evaluation of biomechanical and clinical effects from a literature [French]. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2005; 48:682-689.

- Hunter DJ. Preface. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:xiii-xvi.

- Sharma L, Song J, Felson DT, Cahue S, Shamiyeh E, Dunlop DD. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2001;286:188-195.

- Janakiramanan N, Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, et al. Static knee alignment is associated with the risk of unicompartmental knee cartilage defects. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:225-230.

- Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, Wluka AE, Berry P, Urquhart DM. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:459-467.

- Brouwer GM, van Tol AW, Bergink AP, et al. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1204-1211.

- Personal communications, Dr. Patience White, Chief Public Health Officer, Arthritis Foundation, White Paper in April, 2009.

Research Overview

There is much supportive data regarding the role of pathomechanics in OA. In the preface to an issue of Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America devoted to the topic of OA, Hunter wrote that osteoarthritis “is no longer viewed as a passive, degenerative disorder but rather an active disease process driven primarily by mechanical factors.” He now believes that “mechanics plays a critical role in the initiation, progression, and successful treatment of OA,” and recommends that we “learn from the insights our research is providing to focus even more on important modifiable risk factors such as mechanics.” He adds that, by doing so, “we have the opportunity to make a difference in millions of peoples’ lives.”29

Sharma et al published the results of a study that they believed showed, for the first time, that abnormal alignment of only five degrees (as measured from the ankle to the hip) increased the progression of OA four to five times, and could be seen as soon as 18 months after being identified. They concluded that OA was therefore a result of “local mechanical factors.”30 In their study, Khan et al confirmed that, “previous studies have shown that lower extremity malalignment increases the risk and rate of progression of knee osteoarthritis.”3 Their own study showed that, for each degree of malalignment in people who already had some arthritis there was a 53% average increase risk of its progression. They also found that increasing age was weakly associated with an increase risk of osteoarthritis of the knee. They concluded by noting that alignment has been cited as one of the most important risk factors for the progression of osteoarthritis and that “there is a clear relationship between overall limb alignment and … osteoarthritis of the knee.”

In their study, Janakiramanan et al confirmed Kahn’s findings on the important effect that even the slightest degree of abnormality had on arthritis. According to researchers, even a one-degree abnormality in alignment is associated with an increased risk of cartilage damage in those with arthritis.31 They also reported that malalignment increased joint-space narrowing. A systematic review of the literature published in Arthritis & Rheumatism concluded that, “malalignment of the knee joint was found to be an independent risk factor for the progression of knee OA.”32 One comprehensive study followed more than 1,500 participants for a mean of 6.6 years and found that poor alignment was associated with an increase in the development of osteoarthritis.33

Finally, in April 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Arthritis Foundation organized expert working groups to develop white papers for discussion at an OA summit meeting. More than 80 people from 50 organizations came together to talk about the status of public health interventions for this disease. Their report stated, “the pivotal importance of mechanical factors to osteoarthritis symptoms and progression is undeniable.”34