A 71-year-old patient with advanced knee osteoarthritis (OA) returns for a follow-up visit to the clinic. He says that he’s finally ready for a surgical consult to see if he needs a total knee replacement (TKR). He asks what he should do to get ready for the surgery and whether any exercises would help at this stage.

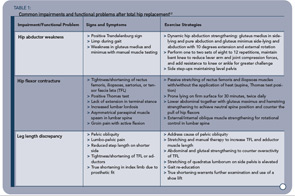

Later in the day, a 44-year-old mother of two with bilateral hip OA secondary to congenital hip dysplasia admits she is anxious about her scheduled surgery. Despite your assurances of pain relief and improved function with total hip replacement (THR), she is scared and uncertain how she will manage the recuperation stage with young children at home. She asks what the rehabilitation involves and how long she will need to do the exercises.

What should you be advising these patients? Should equal effort and formal exercise therapy go into the preoperative (“prehab”) and postoperative (rehab) stages? Where will patients get the “bigger bang for their buck” as one surgeon asked during a recent focus group.1 These are important questions in light of markedly shorter acute care stays, nationwide variance in THR and TKR rehabilitation access and funding, and the lack of evidence-based practice guidelines to help physicians and patients make rehab decisions. Issues regarding the role of both preoperative and postoperative physical therapy (PT) and exercise therapy have been raised by all stakeholder groups: patients, health professionals, orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and general practitioners.1 Furthermore, focus groups have been conducted in Canada and the United States as part of the author’s research to develop practice guidelines for postacute THR and TKR rehabilitation. The purpose of these groups was to explore topics related to rehabilitation current practice and outcomes from varied perspectives and use the results to inform subsequent phases of guideline development.

This interest in the role of exercise in the context of surgery is not surprising since more than 657,000 primary THR or TKR procedures were performed in the United States in 2004. Furthermore, recent estimates suggest that the rate of these procedures will rise exponentially over the next decade, far surpassing the aging of the U.S. population.2 Associated with this rapid increase is an equally steep increase in healthcare expenditures—both direct hospital charges and indirect costs. Based on 2003 National Hospital Discharge Survey data, as much as $3.4 billion is spent annually on rehabilitation services following THR and TKR.3 It is therefore appropriate to consider practical advice for pre- and postoperative exercise to help patients get the most out of their joint replacements.

Preoperative exercise (PREHAB)

“Get yourself into the best shape possible before surgery, because that’s critical,” suggested a 72-year-old retired dental worker during one of the patient focus groups mentioned earlier. Other patients nodded in full agreement. This advice is echoed by the health professional participants. While this is common-sense advice, what does the literature tell us?