Findings to date suggest that individuals with greater preoperative pain, depressive symptoms, significant co-morbidities, and who are sedentary and deconditioned are most likely to benefit from a preoperative needs assessment and prehab interventions.5,6 Investigators in this field are cautious about recommending preoperative exercise to all such patients and suggest further research is needed to identify the most fragile patients and those at risk for poor surgical outcomes.

Despite the lack of evidence on the value of preoperative exercise, many surgeons and other physicians routinely advise their patients to remain physically active, engage in exercises that will help maintain their hip or knee joint ROM and strength of both the lower and upper extremities (in preparation for using walking aids). For individuals with significant joint pain, co-morbidities, or age-related musculoskeletal impairments, or who are significantly overweight, participating in a regular exercise program involving weight bearing and/or resistance training can pose a major challenge. Stationary cycling (upright or recumbent style) and pool-based exercises are good options for these and others awaiting surgery. A physical assessment and an exercise prescription from a PT experienced in arthritis and joint replacement surgery is advised for this subset of patients who may otherwise not exercise.

Postoperative Exercise (REHAB)

Immediately following THR and TKR surgery, muscle strength is typically less than preoperative levels and then begins to rebound by three months after surgery. Meier and colleagues reported isometric and isokinetic quadriceps strength deficits ranging from 15% to 41% compared with the uninvolved side three to six months post-op.7 Muscle strength deficits may remain as long as 13 years following TKR when compared to individuals’ uninvolved side and age-matched healthy peers. Persistent quadriceps (vastus lateralis) weakness has also been reported following THR.8

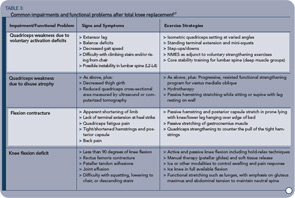

While quadriceps deficits, due to voluntary activation failure and muscle atrophy, are weakly linked to self-reported function, strong ties to functional performance (fall risk, stair climbing, and gait speed) have been identified.7 Similarly, deficits in hip abductor strength following THR are related to reduced functional performance, including postural control.9 A list of common post-THR/TKR impairments and functional problems and exercise strategies for overcoming them are in Tables 1 (p. 17) and 3 (above).

More evidence exists for postoperative exercise and physical therapy compared with the preoperative period. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of PT-prescribed exercise after TKR showed small to moderate treatment effects in favor of functional exercise for ROM, self-reported function, and quality of life three to four months post-op.10 Six RCTs with a total of 614 participants were included in the review and, despite marked clinical heterogeneity among the trials (timing, setting, intensity, and outcomes), five of the studies were pooled for meta-analysis. Interventions ranged from three to 12 weeks in length and were initiated between ten days and two months after surgery. Exercise interventions included isokinetic, isometric, and isotonic strength training; passive stretching; balance training; walking; stationary cycling; sit-to-stand; and stair climbing. Minns Lowe and colleagues concluded that PT functional exercises after discharge result in modest short-term benefits and that exercise programs based on functional activities may be more effective than traditional exercise interventions after elective TKR.10