A 71-year-old patient with advanced knee osteoarthritis (OA) returns for a follow-up visit to the clinic. He says that he’s finally ready for a surgical consult to see if he needs a total knee replacement (TKR). He asks what he should do to get ready for the surgery and whether any exercises would help at this stage.

Later in the day, a 44-year-old mother of two with bilateral hip OA secondary to congenital hip dysplasia admits she is anxious about her scheduled surgery. Despite your assurances of pain relief and improved function with total hip replacement (THR), she is scared and uncertain how she will manage the recuperation stage with young children at home. She asks what the rehabilitation involves and how long she will need to do the exercises.

What should you be advising these patients? Should equal effort and formal exercise therapy go into the preoperative (“prehab”) and postoperative (rehab) stages? Where will patients get the “bigger bang for their buck” as one surgeon asked during a recent focus group.1 These are important questions in light of markedly shorter acute care stays, nationwide variance in THR and TKR rehabilitation access and funding, and the lack of evidence-based practice guidelines to help physicians and patients make rehab decisions. Issues regarding the role of both preoperative and postoperative physical therapy (PT) and exercise therapy have been raised by all stakeholder groups: patients, health professionals, orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and general practitioners.1 Furthermore, focus groups have been conducted in Canada and the United States as part of the author’s research to develop practice guidelines for postacute THR and TKR rehabilitation. The purpose of these groups was to explore topics related to rehabilitation current practice and outcomes from varied perspectives and use the results to inform subsequent phases of guideline development.

This interest in the role of exercise in the context of surgery is not surprising since more than 657,000 primary THR or TKR procedures were performed in the United States in 2004. Furthermore, recent estimates suggest that the rate of these procedures will rise exponentially over the next decade, far surpassing the aging of the U.S. population.2 Associated with this rapid increase is an equally steep increase in healthcare expenditures—both direct hospital charges and indirect costs. Based on 2003 National Hospital Discharge Survey data, as much as $3.4 billion is spent annually on rehabilitation services following THR and TKR.3 It is therefore appropriate to consider practical advice for pre- and postoperative exercise to help patients get the most out of their joint replacements.

Preoperative exercise (PREHAB)

“Get yourself into the best shape possible before surgery, because that’s critical,” suggested a 72-year-old retired dental worker during one of the patient focus groups mentioned earlier. Other patients nodded in full agreement. This advice is echoed by the health professional participants. While this is common-sense advice, what does the literature tell us?

In a systematic review of English language articles published prior to August 2003, Ackerman and Bennel found a limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effectiveness of preoperative exercise programs (physical therapy) on THR and TKR outcomes.4 Of the five studies meeting the review’s inclusion criteria, two pertained to THR and three to TKR, with a combined total of 146 subjects. In the two THR studies reporting outcomes for the same patient cohort, significant improvements were reported for self-reported function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index or WOMAC), hip flexion range of motion (ROM), isokinetic hip strength, and various gait-related parameters at one week pre-op and three, 12, and 24 weeks post-op. The small-to-moderate treatment-effect sizes suggested potentially clinically important differences between the groups. Confounding the results, however, was the fact that the intervention group also received intensive postoperative exercise therapy. The preoperative exercise component consisted of a twice-weekly eight-week customized exercise program comprising stationary cycling, hydrotherapy, and resistive strength training.

Small, statistically nonsignificant treatment effects for self-reported function (Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Rating, Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale), knee ROM, isokinetic knee strength, and walking speed were found for the three TKR trials. However, the trials failed to show clinically important differences between groups in both the pre-op and post-op phases. These preoperative interventions ranged from a five-week group exercise program offered three times per week to six weeks of individualized exercise therapy, also three times per week.

Table 2: Internet resources on joint replacement and exercise

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org

- Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation: www.canorth.org

- myJointReplacement.ca: www.myjointreplacement.ca

- Mayo Clinic: www.mayoclinic.com

- Internet Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma: www.orthogate.org/patient-education

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases: www.niams.nih.gov/health_info

A more recent review conducted as part of the French Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Society’s guideline development process included English and French language papers on preoperative PT, published up to January 2006.5 These authors reported that the heterogeneous nature of the preoperative interventions (differing health care providers, duration, and modes of exercise therapy) prevented the pooling of results. No trials of isolated preoperative exercise therapy were found for THR and only one (included in the previous review) was found for TKR. Nonetheless, the authors recommended a preoperative rehabilitation program comprising PT and education following preoperative assessment to identify those patients most likely to benefit.

A trial published subsequent to these two reviews reported statistically significant improvements in pain and self-reported and performance-based function following a six-week land- and pool-based preoperative exercise program.6 Patients undergoing THR surgery responded better than TKR patients; however, both groups were more likely to be discharged home if they had participated in the exercise intervention.

Findings to date suggest that individuals with greater preoperative pain, depressive symptoms, significant co-morbidities, and who are sedentary and deconditioned are most likely to benefit from a preoperative needs assessment and prehab interventions.5,6 Investigators in this field are cautious about recommending preoperative exercise to all such patients and suggest further research is needed to identify the most fragile patients and those at risk for poor surgical outcomes.

Despite the lack of evidence on the value of preoperative exercise, many surgeons and other physicians routinely advise their patients to remain physically active, engage in exercises that will help maintain their hip or knee joint ROM and strength of both the lower and upper extremities (in preparation for using walking aids). For individuals with significant joint pain, co-morbidities, or age-related musculoskeletal impairments, or who are significantly overweight, participating in a regular exercise program involving weight bearing and/or resistance training can pose a major challenge. Stationary cycling (upright or recumbent style) and pool-based exercises are good options for these and others awaiting surgery. A physical assessment and an exercise prescription from a PT experienced in arthritis and joint replacement surgery is advised for this subset of patients who may otherwise not exercise.

Postoperative Exercise (REHAB)

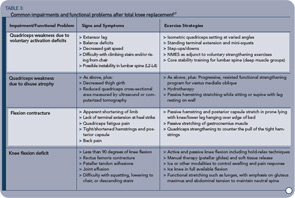

Immediately following THR and TKR surgery, muscle strength is typically less than preoperative levels and then begins to rebound by three months after surgery. Meier and colleagues reported isometric and isokinetic quadriceps strength deficits ranging from 15% to 41% compared with the uninvolved side three to six months post-op.7 Muscle strength deficits may remain as long as 13 years following TKR when compared to individuals’ uninvolved side and age-matched healthy peers. Persistent quadriceps (vastus lateralis) weakness has also been reported following THR.8

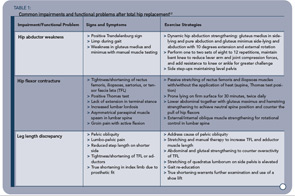

While quadriceps deficits, due to voluntary activation failure and muscle atrophy, are weakly linked to self-reported function, strong ties to functional performance (fall risk, stair climbing, and gait speed) have been identified.7 Similarly, deficits in hip abductor strength following THR are related to reduced functional performance, including postural control.9 A list of common post-THR/TKR impairments and functional problems and exercise strategies for overcoming them are in Tables 1 (p. 17) and 3 (above).

More evidence exists for postoperative exercise and physical therapy compared with the preoperative period. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of PT-prescribed exercise after TKR showed small to moderate treatment effects in favor of functional exercise for ROM, self-reported function, and quality of life three to four months post-op.10 Six RCTs with a total of 614 participants were included in the review and, despite marked clinical heterogeneity among the trials (timing, setting, intensity, and outcomes), five of the studies were pooled for meta-analysis. Interventions ranged from three to 12 weeks in length and were initiated between ten days and two months after surgery. Exercise interventions included isokinetic, isometric, and isotonic strength training; passive stretching; balance training; walking; stationary cycling; sit-to-stand; and stair climbing. Minns Lowe and colleagues concluded that PT functional exercises after discharge result in modest short-term benefits and that exercise programs based on functional activities may be more effective than traditional exercise interventions after elective TKR.10

While Minns Lowe and colleagues excluded trials in which electrical modalities were used as treatment adjuncts, recent evidence suggests that neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) coupled with active quadriceps strength training may help address voluntary quadriceps activation failure and subsequent muscle weakness.7 Similar findings have been reported for optimizing gluteus medius weakness following THR.11 A Cochrane systematic review is underway to examine the evidence on postacute PT and exercise therapy on pain, function, and quality of life after primary THR.12 With seven trials accepted to date, it appears that mixed findings and clinical heterogeneity (timing, setting, intensity, duration, and outcomes) among the RCTs and quasi-RCTs will continue to contribute to the confusion around optimal exercise regimes after THR. Your patients can find additional information on joint replacement and exercise on the Internet. (See Table 2, p.17.)

Final Words

Consistent with the recommendations given by Marian Minor, PhD, PT, in the May 2008 issue of The Rheumatologist (“Exercise to Improve Outcomes in Knee Osteoarthritis,” p. 1), it is important to promote exercise during the office visit by encouraging participation in community-based pool or land programs and identifying those individuals who require additional guidance from a PT to address specific neuromuscular and functional impairments in both the preoperative and postoperative phase. Empowering patients to take an active role in their planning for surgery and post-op rehabilitation will help to prepare them both physically and mentally and ensure they get the most out of their new joint.

Westby is a PhD candidate and physical therapy teaching supervisor at Mary Pack Arthritis Program at Vancouver Coastal Health, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

References

- Westby MD, Backman C. Health professionals’ and patients’ perspectives on rehabilitation and outcomes following total hip and knee arthroplasty: A focus group study. CARE V Meeting, Oslo, Norway, April 25, 2008.

- Kim S. Changes in surgical loads and economic burden of hip and knee replacements in the US: 1997-2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 59(4):481-488.

- Lavernia CJ, D’Apuzzo MR, Hernandez VH, et al. Postdischarge costs in arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2006; 21(6); Suppl 2:144-150.

- Ackerman IN, Bennell KL. Does pre-operative physiotherapy improve outcomes from lower limb joint replacement surgery? A systematic review. Australian J Physiotherapy. 2004; 50:25-30.

- Coudeyre E, Jardin C, Givron P, et al. Could preoperative rehabilitation modify postoperative outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasty? Elaboration of French clinical practice guidelines. Annales de Réadaptation et de Médecine Physique. 2007; doi:10.1016/j.annrmp. 2007.02.002

- Rooks DS, Huang J, Bierbaum BE, et al. Effect of preoperative exercise on measures of functional status in men and women undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 55(5):700-708.

- Meier W, Mizner R, Marcus R, et al. Total knee arthroplasty: Muscle impairments, functional limitations, and recommended rehabilitation approaches. JOSPT. 2008; 38(5):246-256.

- Reardon K, Galea M, Dennett X, et al. Quadriceps muscle wasting persists 5 months after total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip: A pilot study. Internal Med J. 2001; 31:7-14.

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD. Rehabilitation after hip- and knee-joint replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11); Suppl: S98-S118.

- Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey M, Sackley CM. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335:812-820.

- Bhave A, Mont M, Tennis S, et al. Functional problems and treatment solutions after total hip knee joint arthroplasty. JBJS. 2005;87 Suppl 2:9-21.

- Westby MD, Kennedy D, Brander V, Carr S, Backman C, Bell M. Post-acute physiotherapy for primary total hip arthroplasty. (Protocol) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.:CD005957.