SAN DIEGO—Rheumatologists in developing economic regions often face daunting barriers to the provision of basic patient care. In many parts of the world, poverty makes it nearly impossible for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients to afford drugs or even rail transportation to a distant clinic.

In Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and India, healthcare professionals are working together to facilitate better access to medications and to create RA-specific patient registries. Regional rheumatology associations are also publishing RA guidelines that take their area’s unique social, economic and demographic challenges into account, said three rheumatologists who spoke at the 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. (Editor’s note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.)

Rheumatologist Shortage

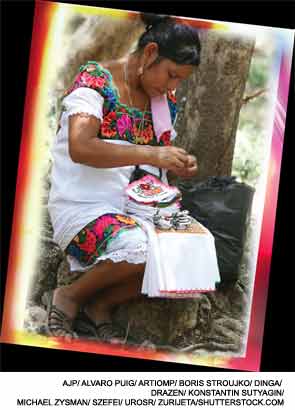

In Latin America and the Caribbean, rheumatologists collaborated through the Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR) to identify six major social problems causing barriers to care, said Jose Antonio Maldonado-Cocco, MD, consulting professor of rheumatology at the University of Buenos Aires School of Medicine, Buenos Aires, Argentina. These included poverty, unemployment, deficiencies in public health, problems in education, socioeconomic exclusion and crime. RA affects about 0.4% of the total population in Latin America. “Ethnic heterogeneity has an impact on prevalence,” said Dr. Maldonado-Cocco, and “creates differences in the clinical expression in relation to genetic factors.” Depending on their ancestry, including descent from indigenous American populations or immigration from Europe or Africa, Latin American RA patients may express a wide array of phenotypes.

In a region marked by poverty, “at least 5,000 specialists are still needed” to meet the World Health Organization’s care standard of one rheumatologist for every 100,000 people, Dr. Maldonado-Cocco said. Low awareness of rheumatic diseases contributes to a dearth of economic and public health policies to improve access to care, he added. “RA is unrecognized as a public health crisis. The public and mostly healthcare administrators are unaware of RA as a catastrophic disease.” Primary care physicians have poor knowledge of RA, causing a delay in referrals to a rheumatologist that leads to a delay in treatment to control disease activity, he said.

In 2006, PANLAR and the Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio de Artritis Reumatoide (GLADAR) published the first position paper on pharmacologic treatment for RA patients in Latin America. New guidelines may help existing rheumatologists make better treatment decisions to help their patients improve quality of life. In Latin America, use of biologic agents is relatively low among RA patients, around 6.4% according to one study, mainly due to cost, he said. “For the average RA patient, biologic therapy would not be cost effective. There would more [quality-adjusted life-year] scores, but at a much higher cost” than traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or corticosteroids, Dr. Maldonado-Cocco said.

PANLAR recently approved the creation of a patient registry of adverse events from biologics. These data may help build support for using biologics in a treat-to-target approach similar to that used in North America and Europe, he said.

In India, Late Referrals Are Problematic

In India, RA patients also tend to see a rheumatologist late in the disease process after significant joint damage has already occurred, said Anand N. Malaviya, MD, visiting senior consultant rheumatologist, A&R Clinic, ISIC Superspeciality Hospital in New Delhi. “Only about 19.5% of RA patients come to us in the early stages of disease. A large number of them are uneducated or poorly educated, and that makes a major difference” in their eventual outcome, he said. “Patients we see are quite disabled by the time they come to us.”

As in Latin America, India has a severe rheumatologist shortage—about one rheumatologist per 6 million patients—and existing rheumatology clinics are crowded. Most RA patients see orthopedists or alternative practitioners, such as Ayurvedics (practitioners of a form of traditional Indian medicine) and homeopaths, Dr. Malaviya said. Indians who are poorly educated lack awareness about RA, and also may be “highly suspicious of Western medicine” and wary of seeking rheumatologic care. These patients may not be referred to a rheumatologist until they develop joint deformities, he added. Patients may have to travel long distances to reach a rheumatology clinic, and many cannot afford the cost of transportation by bus, rail or air. “In India, transportation is user-unfriendly, especially for the disabled,” he added.

Medication cost is an even larger problem for Indian RA patients than transportation, Dr. Malaviya said. Fewer than 5% of Indians have health insurance of any kind, and there is no prescription drug coverage. “Biologics are out of the question for people earning $2 a day,” he explained. Physicians treating RA patients may lack an awareness of such concepts as Treat to Target or Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS-28) scoring, and some physicians may use the same DMARD dosage for every patient regardless of disease activity.

At presentation to his clinic, 46% of RA patients have high DAS-28 scores, and 38% have moderate scores, he said. “Patients are coming in severely deformed. What can we do? A lot!” he noted. Drugs like methotrexate, sulfasalazine and leflunomide are relatively cheap in India, making combination therapy “an excellent option” for controlling disease activity in RA, he said. A relatively high prevalence of type II diabetes mellitus makes high-dose corticosteroid use inadvisable in India, he noted. His New Delhi clinic is using electronic medical records technology to maintain patient data, and they are following a treat-to-target approach to try to lower DAS-28 scores among their patients, he concluded.

Registries Are Blossoming in the Middle East & Africa

In the Middle East and Africa, there is a wide economic disparity across the vast region, as well as a mix of highly disparate cultures, said Mohammed Hammoudeh, MD, chief of rheumatology at Hamad Medical Corp. in Doha, Qatar. In oil-rich countries in the Persian Gulf region, RA patients may be far more likely to have medical coverage or to afford medications, while in sub-Saharan Africa, healthcare is a luxury most cannot afford. In Eritrea, for example, annual per capita government expenditure on healthcare is only $12, he added. Other problems in sub-Saharan Africa include political unrest, which dismantles any government healthcare program, and high incidence of HIV. However, wealthy countries in the region have problems as well; higher rates of cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes are being seen in the Middle East, Dr. Hammoudeh said.

In Latin America, at least 5,000 specialists are needed to meet the World Health Organization’s care standard of one rheumatologist for every 100,000 people.

Functional outcomes among RA patients are generally poorer in this broad region than in more developed economies, and rheumatologists have found it impossible to follow EULAR guidelines to improve those outcomes, Dr. Hammoudeh said. “Across the region, there was low biologic use mainly due to cost,” he said. Overstretched rheumatologists have little time to measure disease activity or physical function scores. “There is a lack of assistants in clinics and a shortage of rheumatologists, especially in Africa. The priority is seen as higher for treating HIV and tuberculosis.” By contrast, in wealthy Qatar, 29% of RA patients are using biologics.

Some of the countries in the region, such as South Africa, have created their own guidelines to take local public health issues into account. For example, high tuberculosis rates make biologic use risky for patients with those two comorbidities, he said. Arab countries have also developed local recommendations for RA treatment, and DMARDs and corticosteroids are mainstays of therapy, he said.

New efforts to create registries, including registries on biologic use and risks in Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates, are signs of hope, Dr. Hammoudeh said. “There is an urgent need for biologics registries in this area. This can serve to help clinicians better serve the population with RA in this area,” he concluded.

Susan Bernstein is a writer based in Atlanta.