GraphicsRF.com / shutterstock.com

Although the diagnosis and treatment of gout are sometimes straightforward, practitioners encounter challenges in patients with atypical presentations, as well as those with medically complex situations or refractory disease. Here, gout experts share insights into some of these scenarios.

Flare in Hospitalized Patients

When not contraindicated, the 2020 ACR Guideline for the Management of Gout recommends colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or glucocorticoids over adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors, such as anakinra, for the initial treatment of gout flare on the basis of their effectiveness, general tolerability and lower cost.1

However, one treatment challenge is managing a concurrent gout flare in a patient hospitalized for other indications, such as sepsis or acute kidney insufficiency. Such concurrent medical issues can limit treatment options for gout and complicate management, as practitioners must weigh the risks and benefits of different potential treatments in the context of the whole medical picture.

For example, practitioners may hesitate to employ steroids in the context of sepsis for fear of increased infectious complications. For acute kidney insufficiency, colchicine and NSAIDs may pose too much of a danger to the kidneys. And some patients have multiple medical contraindications.

Dr. Helfgott

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, director of education and fellowship training in the Division of Rheumatology, Inflammation & Immunity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and the former physician editor of The Rheumatologist, notes, “The rheumatologist first needs to sort out all the confounding issues, which may include renal and cardiovascular events, infection and postoperative issues. All these can influence our choice of medications.”

In general, Dr. Helfgott prefers to use colchicine whenever possible. “Given its relatively narrow therapeutic window for patients with renal disease, sometimes we have to choose other drugs,” he adds. His next choice, if not contraindicated, is glucocorticoids. He also notes that NSAIDs should probably be avoided in most hospitalized patients due to risk of bleeding or acute kidney insufficiency.

John D. FitzGerald, MD, PhD, a clinical professor of medicine and clinical chief of the Division of Rheumatology at the University of California, Los Angeles David Geffen School of Medicine, says, “As in the outpatient setting, selecting the anti-inflammatory with fewest side effects is most important.”

Dr. FitzGerald notes that steroids would be preferred over colchicine and NSAIDs in most cases of acute kidney insufficiency, but if needed, NSAIDs may be used with caution in some patients on dialysis because they can be dialyzed away. For a mono-articulate gout flare, he prefers to try intra-articular steroids, if not contraindicated.

Anakinra can be another helpful option if colchicine, steroids and NSAIDs all carry high risk, Dr. FitzGerald adds. For example, anakinra may be helpful for a patient with diabetes and chronic kidney disease who is having a polyarticular flare or for other medically complex patients.

Dr. FitzGerald

“I reserve anti-IL-1 blockade with anakinra for those rare patients who have either failed prior therapies or cannot tolerate or have experienced severe adverse events with colchicine, NSAIDs and steroids,” says Dr. Helfgott. In contrast to glucocorticoids, anakinra does not exacerbate diabetes, and it does not carry the same cardiovascular risks as NSAIDs, nor the same dosing concerns of colchicine in kidney disease.2

However, anakinra is not an option at all institutions. Lisa K. Stamp, MBChB, FRACP, PhD, a rheumatologist and a professor of medicine at the University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand, notes that anakinra is not available in her country or in many other parts of the world. Instead, Dr. Stamp says, ACTH can be very useful in situations in which these other agents are not advised. It has an excellent safety profile, and its anti-inflammatory action acts in a steroid-independent manner with less immunosuppression than steroids, making it a suitable choice where steroids are a concern.3

Managing Pegloticase

A key tenet of gout treatment is decreasing serum urate levels via urate-lowering therapies, typically allopurinol. But some patients fail to achieve their serum urate target and continue to have frequent gout flares, even after trying xanthine oxidase inhibitor treatment and uricosurics.

For patients who are out of other choices, switching to pegloticase (PEGylated uricase) is an option. Uricase converts urate to a product readily excreted by the kidneys.

“Although pegloticase can be highly effective for select patients who have advanced, severe, tophaceous arthritis, there are many hoops to pass through for this drug to be effective,” says Dr. Helfgott. “The clinician must contend with a plethora of adverse reactions, including loss of efficacy and the potential for severe infusion reactions.”

Like other enzyme-replacement therapies, pegloticase often induces anti-drug antibodies that can cause major hypersensitivity reactions. These antibodies can also reduce response rates to the drug, as well as lead to eventual rising uric acid levels in an initially responsive patient. But some recent reports suggest that immunomodulating therapy (e.g., with methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil) substantially increases rates of response.4

Because pegloticase is usually started as a treatment of last resort, Dr. FitzGerald explains, he universally employs immunomodulation in patients taking pegloticase to reduce the risk of antibody development and drug failure.

However, several available immune-modulating drugs, such as methotrexate and leflunomide, carry a risk of hepatotoxicity and severely limit available choices for immunomodulation, notes Dr. Helfgott, which may be an issue for some patients with gout.

Dr. FitzGerald does not consider pegloticase a long-term option because the cost is prohibitive. He treats most patients until gouty tophi have resolved. But he also notes the choice to stop the medication partly depends on the availability of viable serum urate-lowering therapies for a specific patient based on contraindications and their previous response. If no other options are available, he may continue pegloticase a little longer to significantly lower residual amounts of monosodium urate crystals. He has also treated patients who lack any other options for urate-lowering therapies by cycling pegloticase off and on.

Dr. FitzGerald also notes that he has used clinical exams to evaluate crystal burden, but ultrasound or dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) would also be reasonable choices to determine end of treatment.

Diagnosis in Atypical Patients

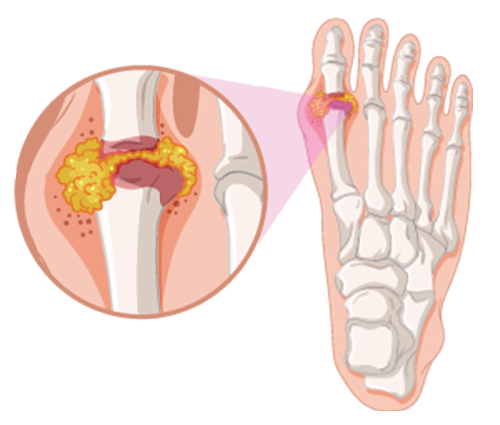

Most commonly, patients with gout present with pain affecting the peripheral joints, often with a monoarticular pattern (especially the first metatarsophalangeal joint), in conjunction with hyperuricemia. However, some patients present with polyarticular small joint involvement or other atypical patterns, which can pose a significant diagnostic challenge.

These atypical presentations may especially be found in certain groups, such as the elderly, patients with enzyme deficiencies, those with prosthetic implants and those on immunosuppressive therapy.5 Gout can also mimic, and sometimes coexist with, other arthropathies, further complicating diagnosis. And hyperuricemia may be absent in up to 42% of patients presenting with their first gout flare.6

Dr. Stamp

Traditionally, gout diagnosis has been based on clinical findings in conjunction with laboratory findings and joint aspirates, with imaging used only if needed. But imaging may be particularly helpful for evaluating atypically presenting patients. DECT and/or ultrasound can play a helpful role in initial diagnosis in patients presenting with atypical patterns, although they may not be available in all clinical settings.

“We have all been confronted with the patient who has been diagnosed with ‘refractory seronegative rheumatoid arthritis’ when, in fact, they had undiagnosed polyarticular gout,” says Dr. Helfgott. “Fortunately, we have dual-energy CT imaging that can be very helpful in confirming the presence of urate deposition in some of these challenging cases.”

Conventional, single-energy CT can demonstrate joint erosions, but it is not very specific.7 In contrast, the dual-source DECT scanner shows much improved contrast between urate and non-urate deposits. A meta-analysis found it had a sensitivity of 0.87 and a specificity of 0.84 (compared with a standard of crystal identification via polarized light microscopy).8

Ultrasound is another helpful imaging option. Among its advantages are its availability, low cost, portability and the absence of ionizing radiation and contrast material. However, it has limited ability to image deep structures, and its success may be highly dependent on the experience and expertise of the operator.7

Dr. FitzGerald prefers ultrasound over DECT for diagnosis of early gout. Although DECT is more specific, he notes, it is also less sensitive early in presentation. One recent study found a false negative rate of 20% in patients with their first flare who had experienced symptoms for fewer than six weeks, potentially because DECT may not be able to pick up the tiny monosodium urate deposits seen in early gout.9

Dr. Stamp points out that taking a detailed history to determine the characteristics of the flares is also extremely important, and any imaging works hand in hand with this. She often starts with plain X-rays as an initial, easily available investigation, which may reveal erosions consistent with gout or evidence of an alternate diagnosis. She notes that, ideally, one should also use joint aspiration to confirm the presence of uric crystals.

One treatment challenge is managing a concurrent gout flare in a patient hospitalized for other indications, such as sepsis or acute kidney insufficiency.

Managing Gout in Post-Transplant Patients

Another challenging area is the treatment of gout in patients on certain immunosuppressants after an organ transplant. For example, some immunosuppressants often used in transplantation contexts, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are thought to increase serum uric acid levels in some patients. This makes gout more of a risk in these patients, and some experience their first gout flares due to the initiation of these drugs.10

Azathioprine is even more of a concern in the context of gout. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase via allopurinol or febuxostat increases the concentration of a metabolite of azathioprine. This leads to higher concentration of the active azathioprine metabolite associated with immune suppression, but also with bone marrow suppression, which can cause potentially fatal blood dyscrasias.11

Close collaboration with the transplant team to determine optimal treatment is key, as sometimes initially prescribed transplant medications can be changed. Dr. Stamp notes, “In general, for patients on azathioprine, we ask whether the patient can be changed to mycophenolate mofetil to allow the introduction of allopurinol. If it cannot, then it can be challenging, as I would avoid both allopurinol and febuxostat.”

Another approach is dose reduction. Notes Dr. Helfgott, “In the azathioprine-treated patient, I consider using allopurinol in a significantly reduced dose—perhaps a 50% reduction from the standard dose, or even less.”

Uricosurics, such as probenecid, are another option. However, they are ineffective in patients with poor renal function. One exception is benzbromarone, which is effective in those with a creatine clearance of greater than 25 ml/min.12 “Benzbromarone is a very useful drug in this situation; however, in many places it is not freely available,” Dr. Stamp adds.

Dr. FitzGerald notes that pegloticase might be an option in this situation, especially as immunomodulators are already required to prevent transplant rejection. Dr. Helfgott also describes another approach: intermittent anti-IL-1 therapy, such as anakinra. “Although this may not lower serum urate levels, it may allow for significant control of gouty episodes without having to prescribe higher doses of steroids on a chronic basis.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Jun;72(6):744–760.

- Saag KG, Khanna PP, Keenan RT, et al. A randomized, phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of anakinra in the treatment of gout flares. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;73(8):1533–1542.

- Daoussis D, Kordas P. ACTH vs betamethasone for the treatment of acute gout in hospitalized patients: A randomized, open label, comparative study. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 27;29(3):178–181.

- Keenan RT, Botson JK, Masri KR, et al. The effect of immunomodulators on the efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021 Apr;51(2):347–352.

- Ning TC, Keenan RT. Unusual clinical presentations of gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010 Mar;22(2):181–187.

- Schlesinger N, Baker DG, Schumacher Jr HR. Serum urate during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997 Nov;24(11):2265–2266.

- Chou H, Chin TY, Peh WCG. Dual-energy CT in gout—A review of current concepts and applications. J Med Radiat Sci. 2017 Mar;64(1):41–51.

- Ogdie A, Taylor WJ, Weatherall M, et al. Imaging modalities for the classification of gout: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Oct;74(10):1868–1874.

- Bongartz T, Glazebrook KN, Kavros SJ, et al. Dual-energy CT for the diagnosis of gout: An accuracy and diagnostic yield study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jun;74(6):1072–1077.

- Afridi SM, Reddy S, Raja A, Jain AG. Gout due to tacrolimus in a liver transplant recipient. Cureus. 2019 Mar 13;11(3):e4247.

- Gearry RB, Day AS, Barclay ML, et al. Azathioprine and allopurinol: A two-edged interaction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;25(4):653–655.

- Stamp L, Searle M, O’Donnell J, Chapman P. Gout in solid organ transplantation: A challenging clinical problem. Drugs. 2005;65(18):2593–2611.