Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is an antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated systemic necrotizing vasculitis that affects the upper airways, lungs and kidneys. It can involve other organ systems, but gastrointestinal (GI) involvement is uncommon. We present the case of a 35-year-old male with a new diagnosis of GPA and severe life-threatening GI manifestations.

Case Report

A 35-year-old white male was admitted to an outside hospital with pneumonia, new skin lesions, and respiratory and renal failure. He was placed on mechanical ventilation. There was concern for vasculitis; labs revealed a low serum complement C4, marked proteinuria and a positive C-ANCA/proteinase 3 (PR3) antibody. An illicit drug screen was negative for cocaine. In addition, the serum cryoglobulins, glomerular basement membrane antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant were all negative.

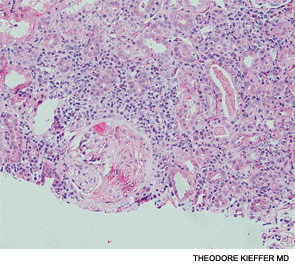

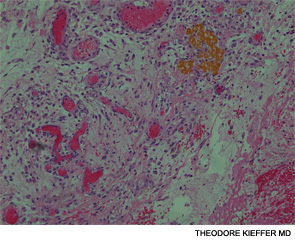

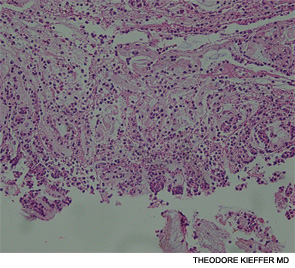

A renal biopsy showed diffuse necrotizing and crescentic pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, consistent with ANCA vasculitis. Patchy acute tubular necrosis, likely secondary to glomerulonephritis, was also seen. Skin biopsy from the dorsum of the hand showed necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Transbronchial lung biopsy on the same day showed distal airway tissue with clusters of neutrophilic necrosis with a focus of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. He was diagnosed with a C-ANCA-positive vasculitis consistent with GPA.

He was treated with methylprednisolone 500 mg intravenously for three days and three cycles of plasmapheresis. Rituximab was chosen for induction therapy, given in a dose of 375 mg/m2 IV weekly for four weeks.1 The steroids were tapered after the pulse dose. He tolerated the first dose of rituximab well, but shortly afterward, he developed severe GI hemorrhage requiring a transfusion of 12 units of blood.

An esophagogastroscopy on the eighth hospital day had shown a normal proximal and middle third of the esophagus. There were a few segments of possible Barrett mucosa extending above the gastroesophageal junction. Focal mild erythema with erosion in the cardia was noted. Because of continued bleeding, he underwent visceral arteriogram the following day, which showed active extravasation from a branch of the gastroduodenal artery and severe hyperemia involving the second and third portions of the duodenum, worrisome for hemorrhagic duodenitis. Three-coil embolization of the gastroduodenal artery was performed. A small (<2 cm) pseudoaneurysm anterior to the right common femoral artery resolved with percutaneous thrombin injection. The patient continued to have episodes of GI hemorrhage and required daily transfusions.

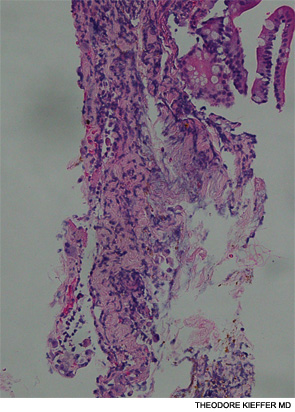

He was transferred to our hospital for further management of the refractory hemorrhage. A small-bowel enteroscopy revealed multiple diffuse ulcers in the third portion of the duodenum. These were thought to be the cause of the recent bleeding. The jejunal wall had adherent clots, but no active bleeding. It was hypothesized that more ulcers might have been present beyond the reach of the scope. The ulcers were clipped and biopsied. The diffuse nature of the ulcers suggested a systemic process, such as a vasculitis. The pathology report, however, described small bowel mucosa with ulceration and no evidence of granulomata or eosinophilic infiltrate.

After transfer to our facility, he had one witnessed tonic-clonic seizure episode lasting less than a minute. He was diagnosed as having posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and started on antiseizure medication. The third dose of rituximab was delayed due to the seizure and hypotension secondary to GI hemorrhage, but he completed a total of four doses of rituximab. The steroids were tapered according to the protocol outlined in the rituximab vs. cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis (RAVE) trial.2

The patient required daily blood transfusions for intestinal hemorrhage. He received aminocaproic acid in an attempt to stop the bleeding. Selective mesenteric angiography with catheterization of celiac and superior mesenteric artery was performed, but no active bleeding was visualized. An attempt to catheterize the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery was unsuccessful.

He had severe pain and worsening abdominal distention. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a large amount of free fluid and extraluminal contrast material with pneumoperitoneum, concerning for bowel perforation. It was believed the small bowel was too diffusely involved for typical mesenteric ischemia, but thickening and edema of the small bowel were attributed to bowel vasculitis. He underwent an exploratory laparotomy with small-bowel resection and enteroenterostomy to repair the jejunal perforation.

The pathology of the resected portion showed a small transmural defect with acute serositis, consistent with perforation. Multiple ulcers were identified in the specimen.

The patient’s skin and respiratory status improved, and he was weaned off the mechanical ventilation. His renal function returned to normal. His course was complicated by the GI manifestations of his disease. Following the bowel surgery, he continued to show improvement; he was placed on tube feedings and started on an oral diet. His GI bleeding resolved completely, and he did not require further transfusions.

Discussion

GPA affecting the GI tract has been infrequently reported in literature. There are case reports of the disease affecting parts of the digestive tract: esophagus, stomach, small intestine or colon.3 Esophagogastroscopy may reveal multiple superficial small ulcerations or small (0.5 to 1 cm) polyps in the esophagus, the stomach or the pylorus. Vasculitis mainly affects the distal small bowel or colon.

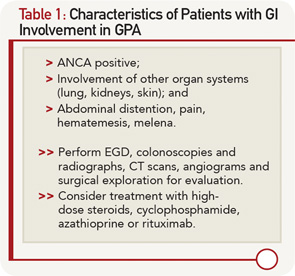

Our patient met the American College of Rheumatology’s 1990 criteria for GPA. He presented with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the lung and skin, and pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis, and was positive for both ANCA and PR3. There were ulcerations on the jejunal biopsy, and focal mild perivascular inflammation was noted in the resected bowel, yet there was no direct, unequivocal evidence of vasculitis. However, the absence of vasculitis findings on bowel biopsy does not rule out GPA. Because the tissue was obtained after the patient received high-dose steroids, plasmapheresis and rituximab, it’s possible the findings of vasculitis were absent because of this immune-suppression therapy. It’s also possible the etiology of the GI manifestations could be linked to other factors. For example, inflammation- and stress-related ulcerations may be slow to heal, especially in patients with renal failure who are receiving concurrent high-dose steroids. Finally, the intractable GI bleeding could be attributed to mucosal sloughing that regressed over time (see Table 1).

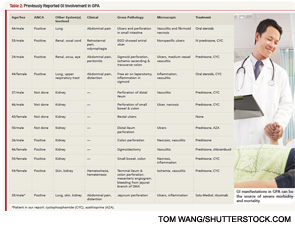

In one case series of seven patients with GPA affecting the small intestine and colon, only three had evidence of vasculitis on biopsy.4 The other patients had ulcerations and inflammation on biopsy. All seven patients had renal involvement and the GI involvement occurred early in the course of the disease, as in our patient (see Table 2). Our patient had evidence of ulcerations and inflammation on the biopsies obtained at enteroscopy and in the resected bowel, but there was no vasculitis seen.

Postmortem studies suggest a higher incidence of GI involvement in GPA than reported, with histological evidence of intestinal vasculitis seen in 24% of cases.5 Perhaps the occurrence of intestinal GPA is underestimated due to asymptomatic involvement or due to immunosuppressive treatments masking symptoms. Our patient presented with persistent and recurrent GI bleeding that overshadowed the other vasculitis manifestations.

In the previous case reports, cyclophosphamide was the drug of choice for induction therapy in GPA patients with GI disease.6 However, we administered rituximab and tapered the steroids according to the RAVE protocol. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of successful treatment of GPA-related intestinal disease with rituximab.

The absence of vasculitis findings on bowel biopsy does not rule out GPA.

Conclusion

Our report illustrates the serious effects of GPA on the GI system. It demonstrates that despite a negative biopsy for vasculitis, the GI manifestations can be the source of severe morbidity and mortality. Early evaluation for bleeding or perforation and close collaboration with the gastroenterology and surgical teams are essential to improve patient outcomes.

Tehniat Haider, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

Steven T. Hugenberg, MD, is the chief of rheumatology and associate professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

Veronica Mesquida, MD, is assistant professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

Mell Gutarra, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

References

- Specks U, Merkel PA, Seo P, et al. Efficacy of remission-induction regimens for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 1;369(5):417–427.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 15;363(3):221–232.

- Arista S, Sailler L, Astudillo L. Relapsing esophageal and gastric ulcers revealing Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Med. 2005 Aug;118(8):923–928.

- Storesund B, Gran JT, Koldingsnes W. Severe intestinal involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Br J Rheumatol. 1998 Apr;37(4):387–390.

- Coward RA, Gibbons CP, Brown CB, et al. Gastrointestinal haemorrhage complicating Wegener’s granulomatosis. Br Med J. 1985 Sep 28;291(6499):865–866.

- Walton EW. Giant-cell granuloma of the respiratory tract (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Br Med J. 1958 Aug. 2;2(5091):265–270.