Designua / shutterstock.com

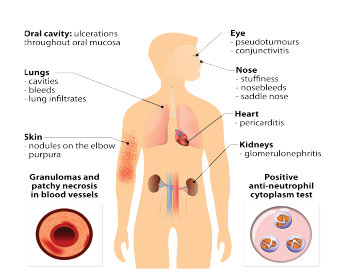

A recent study in Arthritis & Rheumatology highlights new information about the epidemiology and disease course of the vasculitic disease granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly known as Wegener’s disease).1 GPA is a rare disease that’s generally specific to the lungs, kidneys and the upper airways. The study provides key new data about the incidence and prevalence of the disease in the U.S. It also sheds light on disease course and outcomes.

Focus on Children

Information about GPA has been particularly limited for pediatric populations. Due to its relative rarity in children, much less has been known about the disease in this group, with studies limited to small cohorts. Earlier, smaller cohort studies had indicated potential differences in disease course and complication rates for pediatric versus adult populations.1

Andrew J. White, MD, is the emeritus director of the division of pediatric rheumatology and the James P. Keating, MD, professor of pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis, and one of the co-authors of the recent paper. Dr. White and his colleagues utilized a large private insurance claims data set of more than 99 million individuals to retrospectively characterize pediatric and adult GPA patients in the U.S. from 2006–2014. Patients were identified by medical claims forms using the diagnostic code for GPA.1 According to Dr. White, the research included data coded from both inpatient and outpatient encounters. “That’s different than a lot of these types of studies,” he says.

Overall, the researchers identified 5,566 cases of GPA. Of these, 3.8% (214) were pediatric cases. The incidence rate was 12.8 cases per million person-years in working-age adults (i.e., less than age 65), with a lower rate of 1.8 cases per million person-years for children.1

Dr. White

Dr. White says this is roughly consistent with previous estimates. The adult rate is comparable to that of a smaller report from the United Kingdom that reported a rate of 14.0 per million person-years.2 The pediatric rate was also in line with two other much smaller studies that found incidence rates of 2.8 and 0.9 cases per million person-years.2,3

The researchers also studied complication rates. Both children and working-age adults had high rates of hospitalizations and severe infections. “We found that the most common complications were being hospitalized, having a severe infection and having hematologic abnormalities such as cytopenias,” says Dr. White. “We found that hospitalizations were a little more common in children. Of the severe infections, they were mostly of the respiratory tract—pneumonias. The hematologic complications were more common in children than adults as well.” In fact, children had two to three times higher rates of leukopenia, neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Pulmonary infections occurred at a rate of approximately 50 infections per 1,000 person-years in both groups.1

Dr. White says mortality rates were highest in the first year after diagnosis. He adds, “If you can weather the storm of the first year of this disease, you tend to do reasonably well. The early disease course is important.”

An interesting finding concerned the rate of subglottic stenosis. Previous literature indicates the condition is more common in children than adults; for example, a much smaller study from the 1990s found subglottic stenosis was five times more common in children than in adults with GPA.4 However, Dr. White says, “We found it was not quite that blatant.” The researchers noted a trend toward a higher rate ratio of the condition in children vs. adults, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Another notable finding: the rate of end-stage renal disease, which the researchers initially thought might occur infrequently in children. End-stage renal disease was actually observed in 16% of children and 14% of adults (although the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance). In people who did progress to end-stage renal disease, the overwhelming majority developed it within the first year. The time to development was one month on average for children, and four months on average for adults.1 “The time to develop end-stage renal disease was rather fast, which really makes one think that once it hits, it hits hard,” says Dr. White.

Moving forward, Dr. White suggests clinicians be vigilant about treating respiratory tract infections in these patients to potentially help prevent hospitalizations. Noting the higher rates of cytopenias and hematological complications in children, he also recommends being cautious with high immunosuppressive doses in this group, perhaps modifying the dose earlier in the disease course. “I do think kids are probably more responsive to the medicines than adults are; perhaps the kids’ immune systems are a little more compliant,” he says. He explains that in some cases, the optimal medication adjustment for body size may need to be better calibrated, so that pediatric patients don’t receive a higher dose than needed.

Limitations

Dr. White notes one of the study’s limitations: It lacked data for patients over age 65. “Presumably, it’s possible that if you are, say, 75, you might be more likely to have complications,” he says. “We would have liked to have had all ages included in the analysis.”

Another limitation: the fact that people without insurance were not recorded in the database, making it difficult to generalize to the population as a whole. “That’s a bit of a challenge,” he says. “How do you capture the people who don’t submit claims?”

Dr. White says studies looking at large claims databases are becoming more common. Due to technological innovations, researchers are now better positioned to both create these large data sets and later mine them. “It does give you a certain degree of statistical power, allowing you to make conclusions more easily,” he says. “It more accurately describes a situation of a rare disease.”

What the Future Holds

In future studies, Dr. White speculates it would be helpful to see if GPA patients are more prone to infections from specific organisms. He also thinks a prospective trial of patients given different immunosuppressive cocktails (e.g., mycophenolate mofetil vs. cyclophosphamide) may yield useful results.

Dr. White says epidemiological studies for rare diseases are key. “It’s important because with such rare diseases, it becomes difficult if not impossible to do randomized controlled trials prospectively, so you really need to try to look at the population as a whole.”

He says this study included only about 200 pediatric GPA cases, but that a researcher would perhaps want more than that for a randomized controlled trial. “Epidemiology allows us to glean insights that would ordinarily not be obtainable.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Panupattanapong S, Stwalley DL, White AJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) in pediatric and working-age adult populations in the United States: Analysis of a large national claims database. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 May 27.

- Pearce FA, Grainge MJ, Lanyon PC, et al. The incidence, prevalence and mortality of granulomatosis with polyangiitis in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Apr 1;56(4):589–596.

- Grisaru S, Yuen GW, Miettunen PM, et al. Incidence of Wegener’s granulomatosis in children. J Rheumatol. 2010 Feb;37(2):440–442.

- Rottem M, Fauci AS, Hallahan CW, et al. Wegener granulomatosis in children and adolescents: Clinical presentation and outcome. J Pediatr. 1993 Jan;122(1):26–31.