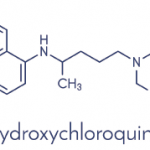

NEW YORK (Reuters Health)—Potentially dangerous prolongation of the QT interval is common among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who receive hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) with or without concomitant azithromycin, according to two new studies.

“This is a well-known problem with HCQ and azithromycin, which became amplified in this higher risk population,” Christina F. Yen, MD, from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, told Reuters Health by email.

In the first study, Dr. Yen and colleagues sought to characterize the risk and degree of QT prolongation in 90 patients with COVID-19 in association with their use of HCQ with or without concomitant azithromycin.

One-third of these patients were critically ill at the time of testing, and 26% were mechanically ventilated. All patients received HCQ, and 59% also received azithromycin. Most patients had at least one cardiovascular mortality and were taking two or more QTc-prolonging medications.

Median corrected QT interval (QTc) was 455 ms at baseline. With treatment the QTc increased by 60 ms or more in 10 patients (11%) and 18 patients (20%) had posttreatment QTc of 500 ms or more.

The number of patients who developed prolonged QTc of 500 ms or more was greater with concomitant azithromycin (11/53, 21%) than with HCQ monotherapy (7/37, 19%), as was the percentage of patients whose QTc increased by 60 ms or more (13% versus 3%, respectively), according to the online report in JAMA Cardiology.1

Concomitant loop diuretic administration and a baseline QTc of 450 ms or more were independently associated with an increased likelihood of prolonged QTc.

Adverse events possibly related to HCQ treatment included intractable nausea, development of new premature ventricular contractions and right bundle branch block, and hypoglycemia.

One patient whose hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin were discontinued because of QTc prolongation (499 ms) developed torsades de pointes three days later and subsequently developed other ventricular arrhythmias that required lidocaine treatment.

“This highlights hydroxychloroquine’s long half-life, allowing QTc prolonging effects to linger even after discontinuation,” Dr. Yen says.

“This study underscores that use of HCQ and azithromycin in hospitalized COVID-19 patients must be done cautiously and ideally in the setting of a clinical trial, as recommended by multiple international guidelines,” she says. “We hope that those seeking to use HCQ, with or without azithromycin, consider our study and other peer-reviewed data regarding the safety and efficacy of these drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. It is not clear that our current understanding of the risk/benefit of HCQ favors its use for COVID-19.”

In the second study, Dr. Martin Cour from Hopital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France, and colleagues evaluated QT intervals in 40 ICU patients with COVID-19 who were treated with HCQ, including 18 (45%) who also received azithromycin. Half of these patients also received other treatments known to prolonged QT.2

Overall, 37 patients (93%) experienced an increase in QTc after administration of HCQ with or without azithromycin.

Significant QTc prolongation was observed in 14 patients (36%), including 10 whose QTc increased by more than 60 ms and 7 whose QTc increased to 500 ms or more, after treatment of 2 to 5 days.

More patients treated with HCQ and azithromycin (6/18, 33%) than with HCQ alone (1/22, 5%) developed an increase in QTc to 500 ms or more.

“Understanding whether this risk is worth taking in the absence of evidence of therapeutic efficacy creates a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed,” write Robert O. Bonow, MD, from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, and colleagues in a related editorial. “Whether signals of potential benefit outweigh signals of harm is unknown until well-controlled clinical trials are completed for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19 infections.”3

Moussa A. Saleh, MD, from Northwell Health, North Shore University Hospital and Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, who also recently reported QT prolongation in COVID-19 patients treated with chloroquine/HCQ with or without azithromycin, tells Reuters Health by email, “The current body of evidence does not support the use of HCQ or azithromycin in COVID-19 patients. The use of HCQ and azithromycin outside of a clinical trial or in the outpatient setting should not occur.”

Dr. Herve Javelot from EPSAN, Brumath and Universite de Strasbourg, France, recently urged that the potential risks and benefits of HCQ-azithromycin treatment be carefully weighed in each situation. He tells Reuters Health by email, “The legitimacy to prescribe the combination can exist, but in the current state of knowledge, its massive use could be dangerous. The benefit/risk ratio is simply not high enough.”

Dr. Cour did not respond to a request for comments.

References

- Mercuro NJ, Yen CF, Shim DJ, et al. Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 1. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bessière F, Roccia H, Delinière A, et al. Assessment of QT intervals in a case series of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection treated with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin in an intensive care unit. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 1. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bonow RO, Hernandez AF, Turakhia M. Hydroxychloroquine, coronavirus disease 2019 and QT prolongation. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 1. [Epub ahead of print]