NEW YORK (Reuters Health)—Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection resolves after effective treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), with most patients remaining in remission for two or more years, researchers from Spain report.

“Most clinical manifestations of the disease improve over time, but some patients may have a clinical recurrence of their disease (cryoglobulinemic vasculitis) after obtaining a sustained virological response,” Dr. Xavier Forns from Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, told Reuters Health by email. “This recurrence is an unexpected result, which must be taken into account by clinicians.”

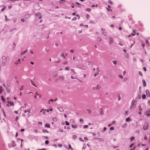

Several studies have shown that patients with HCV-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis have high rates of clinical remission 12 to 24 weeks after DAA therapy. But circulating cryoglobulins persist in up to 50% of patients during short-term follow-up, Dr. Forns’ team notes in Gastroenterology, online April 26.

They assessed the long-term outcomes of 88 HCV-infected patients with circulating cryoglobulins, 46 of whom satisfied criteria for HCV-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (HCV-CV) and 42 of whom were asymptomatic (ACC). All patients achieved sustained virological remission 12 weeks after DAA treatment (SVR12).

During a median follow-up of 24 months (range, 17-41 months), 80% of patients had a complete clinical response, 11% had a partial response and only 9% of patients were nonresponders at last evaluation.

Purpura resolved in 26 of 29 HCV-CV patients, neuropathy improved in 16 of 19, nephropathy resolved in six of nine and 47% had complete neurological responses.

Despite clinical improvements, 20% of both groups (HCV-CV and ACC) had persistent cryoglobulinemia at last follow-up. Overall, 66% of HCV-CV patients and 70% of ACC patients had complete immunological responses at last follow-up.

Five patients (four with underlying cirrhosis) experienced a vasculitis relapse during follow-up, and cryoglobulins became positive or increased in four of these five relapsers. No patient with ACC, however, developed an overt cryoglobulinemic vasculitis during the study.

“Patients can be reassured that their cryoglobulinemic vasculitis will improve once the virus is eliminated, but the risk of recurrence of vasculitis exists and a longer follow-up is necessary,” Dr. Forns said.

“A patient without cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and mild hepatitis C (no fibrosis or mild fibrosis) does not need any further follow-up in the absence of other risk factors of HCV infection or other liver diseases,” he said. “In cases of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, our data would support a longer follow-up to make sure recurrence does not occur over time.”

Dr. Predrag Ostojic from the University of Belgrade, in Serbia, who recently reviewed the management of refractory cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, told Reuters Health by email, “It is believed that antiviral agents, as the only therapy for HCV-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, are not sufficient to treat clinical manifestations of vasculitis. Reaching just one of the treatment goals – reduction of antigens, without reduction of antibodies (cryoglobulins) – by using anti-infective drugs only, may result in less remission and higher possibility of relapses.”