When designing healthcare spaces to foster wellness, you should first understand the particular patient illness being served and then determine that population’s fundamental needs.

“Providers who serve patients with rheumatoid conditions should identify the range of clinical presentations specific to their patient population,” advises Sharon E. Woodworth, AIA, ACHA, EDAC, Healthcare Practice Leader, Perkins+Will Architects, San Francisco, Calif., who refers to this concept as patient-population-based design.1 “Support your patients’ illnesses with environmental features [that] maximize that particular population’s highest level of wellness; in turn, this honors the patient’s condition and, ultimately, instills trust in his or her provider’s care and treatment plan.”

For example, a rheumatologist who primarily sees osteoarthritis patients with joint pain from wear and tear may consider a different office design than a provider who primarily cares for pediatric patients who present with joint pain associated with lupus.

Ms. Woodworth

A rheumatology practice’s ambiance should convey a feeling of comfort, with soothing expressions found in spas or luxury hotel rooms, such as soft colors, subdued decor, carpeted flooring and indirect lighting, Ms. Woodworth says.

Nathan Wei, MD, FACP, FACR, practice owner and rheumatologist, Arthritis Treatment Center, Frederick, Md., says colors convey different images. “Avoid bright, startling colors; an angry orange or red can make a patient feel worse,” he says, noting that his practice features a mauve and teal theme.

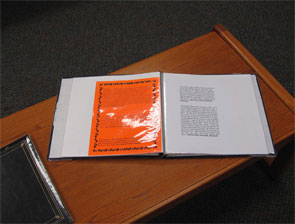

Select furniture with great care. “Furnishings should provide support for patients who have difficulty or discomfort with overly soft seating,” Ms. Woodworth says. “Then arrange it in protected alcoves so the lupus patient, who may be immunosuppressed, can have private seating away from direct sunlight—which can cause a flare.”

Dr. Wei

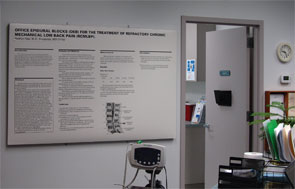

Dr. Wei says chairs and couches should have relatively high arms and seats so patients can get up as easily as possible. On the walls, he hangs mounted posters from sessions he has presented at scientific meetings. “This conveys a sense of authority and expertise,” he says.

Kathleen Roberts, manager, Pain Therapy Associates Ltd., Schaumburg, Ill., says the office features warm, soothing tans and blues, which help to put patients’ minds at ease. Modern furnishings include an open horseshoe-shaped front desk and comfy upholstered chairs with coffee tables in the waiting room. “This makes it more inviting and not sterile, like most practices,” she says.

Dr. Wei, who refers to the waiting area as the welcome area, says windows don’t divide reception staff from the welcome area. “We don’t refer to it as a waiting room,” he adds, “because people don’t like waiting. And our patients rarely wait; they are seen right on time, sometimes even early.”

Appeal to the Senses

Music is a proven source of healing in healthcare environments. “For rheumatoid patients either experiencing pain or concerned about

Furniture should be selected to provide support for patients who have difficulty with overly soft seating.

Image Credit: Courtesy Perkins+Will/Ken Hayden

immunosuppression, research has proved that music raises pain thresholds and is effective in significantly increasing immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies, which is key in providing defense [against] various infections,” Ms. Woodworth says.2

Research shows that what type of music is most successful varies greatly. “Considering the rheumatoid population can be broad in terms of age and condition, the provider might offer a choice of music via an inexpensive iPod,” Ms. Woodworth says. “Silence is an option, but keep in mind that when ambient noise isn’t offered, every sound grabs attention. Ambient noise generated by television has its plusses and minuses, and can be especially negative if the programming does not filter out potentially stressful stories that are popular in our sensationalist-oriented news environment.” Practitioners can alleviate this by using closed circuit television or simply offering the TV as a monitor for movies that patients can choose.

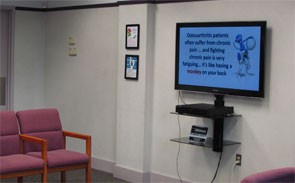

Dr. Wei’s welcome area features a large-screen television that rotates his short videos (about one-and-a-half minutes long) on different topics, such as how acupuncture might help certain conditions and the side effects of inflammatory drugs. “They are short, to the point and visually appealing,” he says.

He advises against music. “You hear it so often, it can be irritating,” Dr. Wei says. Instead, he suggests soothing sounds, such as birds chirping.

This device emits a pleasant smell

courtesy Nathan Wei

Pain Therapy Associates’ waiting area has a flat-screen TV that plays DVDs featuring beaches, waves, fish, deserts and canyons, accompanied by soothing music. “Patients find the DVDs very relaxing,” Ms. Roberts says. “In fact, many patients ask for the DVD titles so they can go out and purchase them.” In an effort to portray a family atmosphere, the practice doesn’t show medical videos.

Although the other senses are not as dependent on rheumatoid patients’ sense of well-being, offering water or other refreshments sends the message that you care while your patients wait, Ms. Woodworth says.

Ms. Roberts says staff offer coffee or water to every patient. In fact, the practice’s medical director, Carey Dachman, MD, FACR, DAAPM, gets it for patients, who are often pleasantly surprised by this.

Dr. Wei says the olfactory sense is often overlooked. His welcome area features the Encore Plus Metered Dispenser System that emits a subtle, pleasant smell. Employees offer beverages, including bottled water (the favorite) and, sometimes, coffee, tea or juice.

The TV in the reception area plays the physician’s videos on YouTube.

courtesy Nathan Wei

Interactive items should not frustrate rheumatology patients or make them feel inadequate. For example, a touch-screen TV control is less painful and easier to maneuver than a small-button TV remote. Books or toys for children create a level of familiarity and comfort in what they could perceive as a stressful environment. “Because this patient population can be broad in terms of age and condition, it’s best to offer a range of interactive items; giving patients a choice also instills a sense of trust and ownership in their own care,” Ms. Woodworth says.

Pain Therapy Associates offers current magazines, including free consumer arthritis magazines that patients can take home. “We don’t display anything older than a month,” Ms. Roberts says.

Arthritis Treatment Center has three or four jigsaw puzzle tables set up, which many patients seem to enjoy.

Great Greetings

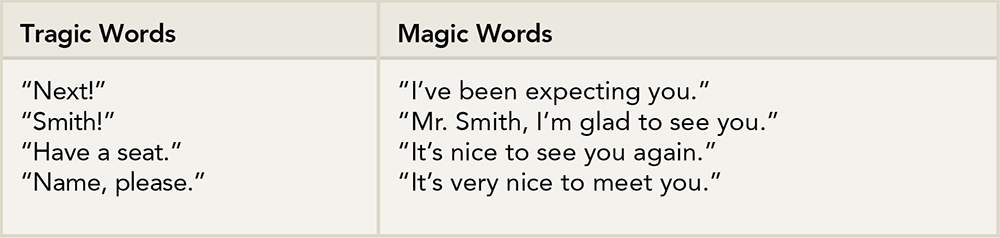

Advice from Wendy Leebov, EdD, managing partner, Language of Caring LLC, Boynton Beach, Fla.

Tips for Initial Contact

Along with a practice’s appearance, how staff interact with patients is equally important—beginning with the initial phone call. Dr. Wei, who despises voicemail, says during office hours a live person almost always answers phone calls by the third ring. The receptionist identifies the practice and herself, followed by, “How may I help you?”

“I think that sets the tone that we are a little different; it’s a pleasant surprise,” Dr. Wei says. Then, the receptionist obtains typical patient information and mails the patient a “shock-and-awe package.” In it, a questionnaire aims to collect as much information as possible so Dr. Wei can get to know the person beyond his or her condition. The package is also a way for Dr. Wei to establish his expertise and authority. It contains information that pertains to the patient’s specific problem, as well as patient testimonials, videos, DVDs and CDs that are informative and instructive. “It’s a fairly thick package that prepares the patient for the initial visit,” he says.

Lydia Ramsey, president, Manners That Sell, Savannah, Ga., suggests sporting a smile before even picking up the phone. “Smiles can be heard over the phone,” she says.

This reception area has an open design.

courtesy Nathan Wei

A jigsaw puzzle can keep minds occupied and provide hands with some dexterity practices and exercises while patients wait to see the doctor.

courtesy Nathan Wei

Chairs and couches should have high arms to provide

support for patients who have difficulty standing up.

During a conversation, never put callers on hold without asking for and receiving their permission to do so. “If you need to transfer a call, make sure the person to whom you are sending the call is in the office and is able to help the caller,” Ramsey continues.

Dr. Leebov

When answering a call, Wendy Leebov, EdD, managing partner, Language of Caring LLC, Boynton Beach, Fla., advises stopping your work and answering a call within four rings. “Stop any office conversation you may be involved in, and turn your attention to the phone,” she says.

“Listen attentively to the caller,” Dr. Leebov continues. “Concentrate on what he or she is saying. Take the time to determine the caller’s needs.”

Poster presentations convey a sense of authority.

courtesy Nathan Wei

If you have trouble understanding the caller, tactfully interrupt and say, “I’m having difficulty hearing you. Would you mind repeating that?” Dr. Leebov says. Or, “I’m having difficulty understanding you. Would you mind repeating that slowly, since I want to make sure I’m clear on how I can help you?”

Be careful to speak clearly and distinctly yourself. Avoid being too casual (“Who’s this?”) or too formal (“May I ask to whom I am speaking?”). “Strive to sound professional, without sounding cold and uncaring,” says Dr. Leebov, who suggests using, “May I ask who’s calling?”

Dr. Wei agrees that language is important. “When a patient says, ‘Thank you,’ our employees are trained to say ‘My pleasure’ rather than ‘No problem.’ This conveys a much more positive response,” he says.

“A practitioner should articulate his or her commitment to excellence and personalized service, and communicate that you expect your staff to demonstrate this as well,” Dr. Leebov says.

Making Patients Feel Welcome

Ms. Ramsey

The person who greets patients should always make eye contact and smile immediately. “Even if the receptionist is in the midst of another task, he or she should acknowledge the patient’s presence with a smile and a nod,” Ms. Ramsey says.

Use the right words when asking the patient to complete any forms. “Say, ‘Would you please fill out these forms and then return them to me?’ Don’t order them to complete them. ‘Please’ is a key word and should be offered with a smile,” she says.

When the patient returns the form, say “Thank you” and explain what to expect next. “Patients should not have to wonder what your procedures are, especially when they are new to the office,” Ramsey says. “Keep patients apprised of approximate wait times. If you expect a long delay, ask the patient if he or she would prefer to reschedule. Some offices post wait times, which is very helpful.”

Dr. Wei also emphasizes the importance of making eye contact. “With the proliferation of electronic medical systems, all too often your eyes are glued to a computer monitor and you never look up—which is a huge mistake,” he says. “Patients crave eye contact and the intimacy that comes with personal interaction.”

Patients can read testimonials about their physicians from other patients in this handy notebook.

courtesy Nathan Wei

Attention to Detail

The little things that you and your staff do will make a lasting impression. Pain Therapy Associates offers fat pens for patients to use, because they are easier to grasp. Doors have handles, not knobs that are hard to turn. Patients wear comfy gowns, not paper ones.

Ramsey advises prepping staff on appropriate office attire. “Some may need to wear uniforms, but may have to be reminded to keep their uniforms clean, neat and pressed,” she says. “Provide guidelines to staff members who do not wear uniforms. Enforce dress codes.”

Dr. Wei’s entire staff wears teal or mauve scrubs—the practice’s colors—for a uniform look, as well as name tags.

Focus on the Patient

“We try to make this experience as pleasant as possible,” Dr. Wei concludes. “When someone has a rheumatoid condition, he or she is often hurting. The last thing we want is for the patient to hurt more, either physically or emotionally.” Keep these things in mind when striving to make your practice a safe haven for patients.

Words to Practice By

Carey Dachman, MD, FACR, DAAPM, medical director, Pain Therapy Associates Ltd., Schaumburg, Ill., shares his practice’s philosophy regarding patients.

- Our patients are the most important people.

- Our patients are not dependent on us; we are dependent on them.

- Our patients are not an interruption of our daily schedule; they are the purpose of it. We have an opportunity to be of service to them.

- Our patients are not outsiders to our practice; they are our practice.

- Our patients are not names on file cards or ledger sheets; they are human, with feelings and emotions like our own.

- Our patients are not to be argued with; nobody ever won an argument with a patient.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Woodworth SE. Population-based design: A needs-assessment approach for designing healthcare environments. Academy of Architecture for Health Journal. March 2015.

- Lane D. The effect of a single music therapy session on hospitalized children as measured by salivary immunoglobin A, speech pause time, and a patient opinion Likert scale. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation.] Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. 1990.