Systemic sclerosis (SSc), a subtype of scleroderma, is a rare, complex autoimmune disease characterized by widespread vasculopathy of the small arteries and fibroblast dysfunction.1,2 It has been described as a fibrosing microvascular disease, because vascular injury precedes and leads to tissue fibrosis.3 The resulting Raynaud’s phenomenon, pain, skin thickening and tightening, and multi-organ involvement have a significant impact on daily function.2-7

Two subtypes of SSc: limited and diffuse systemic sclerosis (dSSc). Both types involve Raynaud’s, gastrointestinal dysfunction and cutaneous fibrosis of the face, forearms, hands and fingers, but dSSc is the more severe of the two because it also affects the trunk, lower extremities and internal organs. Moreover, dSSc is progressive and has a 10-year survival rate of about 67%.8,9

A major impact on quality of life for individuals with dSSc is loss of hand function due to pain, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ulcers and acro-osteolysis.3,4,10,11 Caused by pathologic vasoconstriction of the small vessels of thermoregulation and exacerbated by stress and cold, Raynaud’s is usually the first clinical symptom of dSSc.3 It is a source of substantial pain and disability in dSSc.1,3,4,12,13

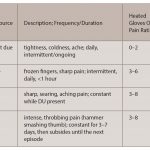

Figure 1

Manifestations of diffuse systemic sclerosis are visible in the hands: shortening of distal phalanges due to acro-osteolysis in bilateral thumbs (A–C), ring finger (B) and left middle finger compared with the right (D); thumbs fully flexed (C). Note color changes (A–D), overall shortening (B), digital pitting scars (arrows), swollen fingers and tight, shiny skin (A,D).

In addition, and often quite devastating to patients, ischemic digital ulcers (DUs) develop in more than 50% of patients with dSSc.14 DUs are extremely painful and often take weeks to heal.10,11,14‑16 They impair hand function, and to further complicate the disability, these ulcers frequently recur.4,17,18

Another source of pain is acro-osteolysis, the resorption of the distal phalanges of the digits. Acro-osteolysis is associated with the vasculopathy and tissue hypoxia inherent in dSSc.5 This process results in overall shortening of the affected fingers. Loss of function is more pronounced when the index fingers and thumbs are involved.19

There is no cure for dSSc, but there are conservative treatment approaches and drug therapies to manage symptoms and to address internal organ involvement.7,14,20 Current evidence supports the use of vasodilators, such as amlodipine, to reduce vasospasms in Raynaud’s.3 Cyclophosphamide and azathioprine, both immunosuppressants, are often prescribed, yet have no direct benefit to hand function.7,20 Thus, it is important to adopt a patient-centered approach to the treatment of dSSc.

According to Carol Tresolini and the Pew-Fetzer Task Force at the University of California, San Francisco, “To be therapeutic, the relationship between healer and patient should have as its foundation a shared understanding of the meaning of the illness.”21

Medical providers have focused primarily on the major medical complications of dSSc and, thus, most often prescribe medications.13,16,18,22 However, patients with dSSc focus on pain and function.12,18 Raynaud’s and digital ulcers are devastating for people who are often working, caring for themselves or caring for others. Loss of function and inability to go outdoors in the cold limit both work and family activities.

Multiple modalities have been investigated to address hand limitations in dSSc, including heat, paraffin, gloving and stretching exercises.23-27 However, in research studies, heat is typically applied for short durations of 15 to 20 minutes. Moreover, few, if any, studies address the effects of heat on pain, Raynaud’s, ulcers or acro-osteolysis.

Historically, researchers formulate research questions and design a study to answer those questions. Participant input is minimal. More recently, groups including PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) and SPIN (Scleroderma Patient-Centered Intervention Network) have spotlighted the need for research studies to focus on outcomes meaningful to the patient population.12,28 In dSSc, as well as other major life-threatening and life-changing illnesses, patient-centered approaches offer a unique opportunity for patients to participate in their own care and inform designs for future research, including research questions, interventions and outcomes.12,28

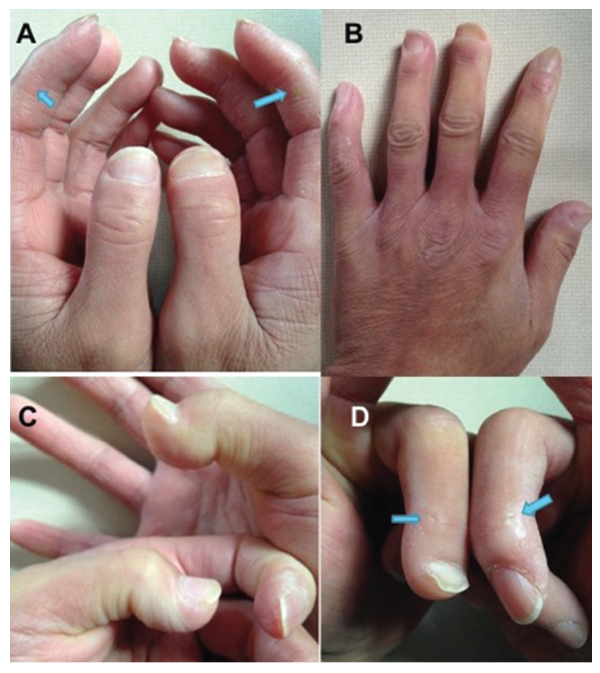

Figure 2: Heated Gloves in Action

The heated gloves can be worn alone or under other gloves. They are shown here (A) covered with vinyl gloves during cooking, (B) covered with knit and vinyl gloves to make a snowman (45 minutes), powered by a wall adapter for home (C) and a car adapter while driving (D) (blue arrows).

Barb, a healthcare professional and patient with dSSc, undertook a personal study examining the use of continuous superficial heat via battery-operated heated gloves. Use of continuous superficial heat has not been investigated and may provide beneficial results for patients with dSSc. She researched the topic through publicly available online databases, including PubMed, and used her clinical and personal experiences using heat to address pain, Raynaud’s, DU and range of motion (ROM) to formulate her research question and to design a study to answer the question.

Research question: How does the prolonged application of heat affect digital pain, ulcer development and hand function in a patient with dSSc?

Case Study

History: Barb, a 50-year-old physical therapist, developed Raynaud’s phenomenon in December 2008. Immediately thereafter, in January 2009, she developed severe bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. After undergoing bilateral carpal tunnel releases, the neurological symptoms resolved, but tightness and swelling in the hands continued.

Barb was officially diagnosed with dSSc in June 2009. Skin edema and fibrosis rapidly progressed from her wrists and hands to painful full-body involvement by October 2009. Weighing the risk vs. benefit profile of available drugs to treat dSSc, Barb declined a major medication regimen and chose the more conservative treatment of aspirin, as well as conservative management of symptoms.

In 2011, she was evaluated by a rheumatologist who specialized in the diagnosis and treatment of SSc. This specialist provided education and instruction on dSSc and Raynaud’s management, as well as pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment options. His recommendation for Raynaud’s management and DU prevention was to initiate amlodipine and avoid exposure to cold, while keeping the hands warm. Because her heart, lungs and kidneys were stable, Barb again chose conservative measures—knit gloves and chemical hand warmers—to address Raynaud’s until signs and symptoms required pharmaceutical intervention. The physician supported her decision and scheduled regular follow-ups.

By January 2012, while other symptoms including full-body skin pain, itching and skin thickness began to subside, the skin on her hands remained tight. In addition, circulatory disturbances continued to be a problem (see Figure 1). In November 2012, Barb developed painful acro-osteolysis in her right thumb and an ulcer on her left 2nd digit. Amlodipine was initiated to assist with conservative management.

In 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 between November and February, Barb developed an ulcer on her left index finger. She applied basic wound-healing techniques and held hand warmers nearly constantly. However, holding the hand warmers hindered her hand function, did not adequately heat her fingertips nor prevent DUs. In 2015, she started wearing heated gloves intermittently, but she could not identify any research to support this or to support wearing heated gloves continuously for hand dysfunction management in dSSc.

Patient-Identified Problems

Impaired bilateral hand function due to:

- Pain secondary to tender fingertips, Raynaud’s, acro-osteolysis, vasculopathy;

- Impaired skin integrity of both hands;

- High risk for DU due to vasculopathy, dSSc disease process and prior history of ulcers;

- Decreased active range of motion (AROM) in all digits due to tissue tightness, shortening of fingers and interstitial edema;

- Decreased strength in both hands; and

- Reduced protective sensation in both hands.

Patient-Identified Goals

- Protect hypersensitive fingers from trauma and injury;

- Decrease digital pain;

- Prevent DUs;

- Prevent Raynaud’s episodes; and

- Increase or maintain hand AROM.

Patient-Centered Intervention

(click for larger image)

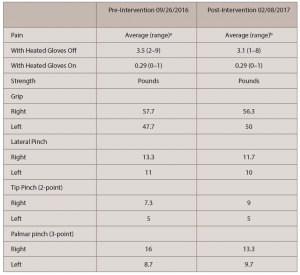

Table 1: Pre- & Post-Measures for Pain & Hand Strength

a Calculated from NRS ratings from Dec. 6–Dec. 12, 2015, with intermittent heated-glove use

b Calculated from NRS ratings from Jan. 1–Jan. 31, 2017, with daily, continuous (>6 hours) heated-glove use

Note: NRS=Numerical Rating Scale

The study intervention was battery-operated heated glove liners (Motion Heat, Calgary, Canada), referred to as gloves in this article. The gloves are heated by non-metallic fibers woven into the gloves and connected to 12-volt rechargeable lithium batteries. The batteries are housed in a zippered pocket in each cuff. In addition to the portable batteries, wall and car adapters were used to power the gloves. Three settings of 84ºF, 104ºF and 122ºF were adjusted as often as needed to ensure a comfortable level of heat as determined by the wearer. The gloves provided continuous heat from the dorsum of the hand to the tips of the fingers and thumbs.

Primary Outcome Measures

Pain: The numeric rating scale (NRS) is an 11-point rating scale with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst imaginable pain. It has excellent test-retest reliability (r = 0.95) for chronic pain when four ratings per day are taken daily for seven days.29-31 A single measure of pain is not a reliable or valid measure of pain in patients with chronic pain. To maximize reliability and validity of pain measures, averaging multiple measures across time is important.29 Construct validity (r = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.93–0.95) was high, with excellent correlation between NRS and visual analog scale.32 Farrar et al reported that a reduction of two points represented a clinically important improvement in chronic pain.33

Ischemic Digital Ulcers: Digital pitting scars and digital ulcers are two digital lesions resulting from ischemia due to Raynaud’s and dSSc vasculopathy.10 Digital pitting scars are small pits and areas of hyperkeratosis on the finger.10 They can be precursors to DUs. An ischemic DU is defined as a denuded area with well-demarcated borders, involving loss of epidermis and dermis, located distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint on the pulpar surface of the fingertip.14,18 Traumatic ulcers, located on the extensor surfaces of the digits, are not addressed in this article because they are not classified as ischemic DUs.14

Secondary Outcome Measures

Strength: Using the standardized test protocol for hand and pinch strength recommended by Mathiowetz et al, grip strength was measured with a hydraulic hand dynamometer (Baseline, White Plains, N.Y.).34 The hand dynamometer has a concurrent validity of 0.9994 and 0.9997 before and after study with known weights in healthy adults.35 Pinch was measured with a hydraulic pinch gauge (JAMAR, Sammons Preston Inc.).

Active Range of Motion: Goniometers were used to measure flexion and extension of bilateral wrists and 2nd and 5th digits, using the procedures described by Norkin and White.36 Intrarater reliability of the Roylan finger goniometer is good with ICC 0.67–0.85 for active ROM.37

Sensation: The West Enhanced Sensory Test (WEST, Danbury, Conn.) was used to assess sensation. The tips of different diameter monofilaments were pressed onto Barb’s finger to determine the smallest amount of bending force she could detect. The monofilaments were scored in terms of grams (g): 0.07 g within normal range, 0.2 g reduced tactile, 2.0 g reduced protective, 4.0 g loss of protective and 200 g residual sensation. Uddin et al used weighted kappa and percent agreement to indicate test–retest reliability of the WEST and used the percentage of normal controls that achieved a normal score to determine validity.38 Test-retest reliability was excellent (k = 1). Average percentages of normal detection on one test–retest (detection level = 4/5) was 93% and 97%; another (detection level = 5/5) was 82% and 85%.

Dexterity: Dexterity was assessed with a nine-hole peg test. The object was to insert nine pegs into holes and remove them as fast as possible with one hand. This was conducted with right and left hands as recommended by Mathiowetz et al.39 In healthy adults, test–retest reliability coefficients were 0.95 right hand and 0.92 left hand.39 This test showed good criterion validity with adequate correlation (P = -0.74 to -0.75) with the Purdue pegboard and excellent correlation with the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (P = -0.87 to -0.89).40

Hand Function & Joint Mobility: Functional mobility was assessed using the Hand Mobility in Scleroderma (HAMIS) test. The test consists of nine items that assess finger flexion and extension, finger and thumb abduction, pincer grip, wrist flexion and extension, pronation and supination. Both hands are assessed and graded separately. Each item is graded 0–3, with 0 indicating the subject can perform the action and 3 denoting the subject cannot perform the action. A maximum score of 27, for each hand, indicates a high degree of hand dysfunction.41 The HAMIS has an excellent test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.99).42

The Modified Kapanji Index (MKI) was used to assess joint mobility.43 The MKI scores thumb opposition and long finger flexion and extension using numbered anatomical landmarks on the hand, such as the tip of the 5th digit and the flexion creases on interphalangeal joints. Each landmark is numbered in order, starting with 1. The higher numbers require greater ROM. The highest number the thumb or finger can reach on its respective hand is the score for that finger. The sum of scores for finger ROM and thumb opposition for right and left hands are combined. A maximum score of 100 indicates normal mobility. MKI has good interobserver reliability (ICC 0.9, 95% CI range from 0.821–0.944) and correlates well with the goniometer.43

Pre-Intervention Measures

On Sept. 26, 2016, an occupational therapist collected Barb’s baseline data, including pain, DU, hand strength, AROM of bilateral wrists and 2nd and 5th digits, sensation, dexterity, HAMIS and MKI. Initial patient measures are summarized in Tables 1–3.

Primary Measures

Pain: Baseline average pain with and without heated gloves was calculated using fall and winter 2015–2016 data. At that time, Barb wore the heated gloves intermittently for Raynaud’s pain management, then more frequently and for longer durations when the DU on her left second digit returned in November. NRS ratings with and without gloves captured pain from Raynaud’s, DUs and acro-osteolysis. Pain was assessed daily, three to four times per day between Dec. 6, 2015, and Dec. 12, 2015, and averaged over the seven days. Mean pain with heated gloves off was 3.5 and ranged from 2–9. Average pain with heated gloves on was 0.29 and ranged from 0 to 1.

Ischemic Digital Ulcers: There were multiple digital pitting scars in bilateral fingers and thumbs, but no DUs were present.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Strength: Strength was assessed in both hands. Right and left grip strength were 57.7 and 47.7 lbs., respectively. Lateral pinch was 13.3 lbs. on the right and 11 lbs. on the left. Two-point pinch was 7.3 lbs. on the right and 5 lbs. on the left. Three-point pinch was 16 lbs. on the right and 8.7 lbs. on the left.

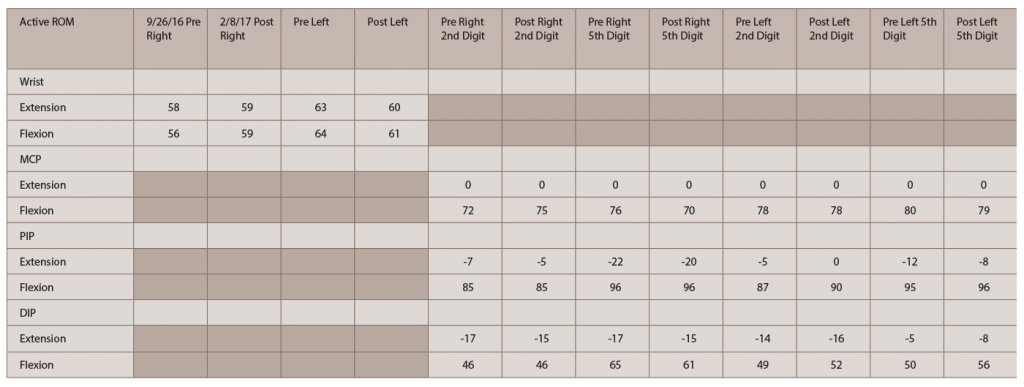

Active Range of Motion: Active extension and flexion of the right wrist was 58º and 56º, respectively. Left wrist extension was 63º, and flexion was 64º. See Table 2 for 2nd and 5th digit values (p. 41).

(click for larger image)

Table 2: Active Range of Motion of Bilateral Wrists & Digits 2 & 5

Note: MCP=Metacarpophalangeal joint; PIP=Proximal interphalangeal joint; DIP=Distal interphalangeal joint

Sensation: All digits on the right hand scored 2.0 g, reduced protective sensation. The left thumb and digits 3–5 scored 2.0 g, reduced protective sensation. The left 2nd digit scored 4.0 g, loss of protective sensation.

Dexterity: On the nine-hole peg test, the right hand score was 21.83 seconds, and the left hand score was 21.92 seconds.

Hand Function & Joint Mobility: HAMIS test scores were 7 for the right hand and 1 for the left. Total score for Kapanji Modified Index was 78 out of a possible 100 points.

Intervention

Between Sept. 27, 2016, and Feb. 8, 2017, Barb wore the heated gloves at least six hours per day while awake, seven days per week (see Figure 2). In addition, she wore them during Raynaud’s episodes, when her fingers were painful, and when her fingers were cold or uncomfortable. Wearing time and pain ratings were documented on a calendar. Knit or vinyl gloves were worn over the heated gloves for protection from dirt and moisture. Gloves were removed for activities of daily living and when wearing them was not feasible. No formal ROM or strengthening exercises were performed during the intervention period. Barb continued task modification and finger protection strategies. Medication consisted of aspirin and amlodipine, as per her usual regimen. No pain medication was used.

Post-Intervention Measures

Post-intervention data was collected on Feb. 8, 2017, as shown in Tables 1–3 (pp. 35, 41 and 42). Between the intervention period of Sept. 26, 2016, and Feb. 8, 2017, Barb wore the heated gloves 8–16 hours per day, with an average wearing time of 10 hours per day.

Primary Measures

Pain: Post-intervention pain averages were calculated from Jan. 1–31, 2017. NRS ratings with and without gloves captured pain from Raynaud’s and acro-osteolysis. Post intervention, pain with gloves off averaged 3.1 and ranged from 1 to 8. Pain with gloves on averaged 0.29 and ranged from 0 to 1 (see Table 1).

Ischemic Digital Ulcers: No DU developed during the intervention period (see Figure 3).

Secondary Measures

Strength: Grip strength decreased 1.4 lbs. in the right hand and increased 2.3 lbs in the left. Right and left lateral pinch decreased 1.6 lbs. and 1.0 lb., respectively. The right three-point pinch decreased 2.7 lbs. There were increases in the right two-point pinch, 1.7 lbs., and the left three-point pinch, 1.0 lb. (see Table 1).

Active Range of Motion: There was a 1º increase in active right wrist extension and 3º increase in wrist flexion. Left wrist extension and flexion each decreased by 3º. The right second digit active ROM increased in all joints by 2–5º. The right 5th digit decreased MCP and DIP flexion by 6º and 4º, respectively. The left 2nd digit increased PIP extension 5º and both PIP and DIP flexion by 3º. The left 5th digit increased PIP flexion 2º and DIP flexion 3º. There was a decrease in MCP flexion by 1º and DIP extension 3º (see Table 2).

Sensation: Sensation improved in the left 2nd through 5th digits and the right 4th and 5th digits. The left 2nd digit improved from 4.0 g, loss of protective sensation, to 2.0 g, reduced protective sensation. The left 5th digit improved from 2.0 g, reduced protective sensation, to 0.07 g within normal range. An improvement from 2.0 g, reduced protective sensation, to 0.2 g, reduced tactile sensation, was noted in the left 3rd and 4th digit and the right 4th digit (see Table 3).

Dexterity: Barb completed the nine-hole pegboard test faster by 1.33 seconds with her right hand and by 3.72 seconds with her left hand (see Table 3).

Function & Joint Mobility Tests: The HAMIS test score improved in the right hand by two points, but not in the left. The Modified Kapanji Index showed an improvement in right thumb opposition and right and left long finger flexion. Total score was 84 out of 100 points (see Table 3).

Discussion

In this case study, continuous use of heated gloves provided protection and addressed the vascular issues in dSSc. The daily use of heated gloves for more than six hours per day provided continuous warmth to Barb’s fingertips. In turn, her pain was decreased, and no digital ulcers formed during the intervention period. Barb credited the gloves with preventing or stopping Raynaud’s episodes quickly, thereby enabling her to use her hands more readily.

Heated gloves are neat and effective. The gloves freed up her time and her hands, and enabled her to more comfortably complete tasks and function in cold environments. She achieved her goals.

This study provides a unique physical therapist–patient perspective on unreported characteristics of dSSc and management of functional limitations imposed by the disease. Barb, eight years post progressive dSSc diagnosis, had had recurrent DUs yet experienced decreased pain and no DUs during the four-month intervention of daily, continuous use of heated gloves. The incapacitating pain associated with active acro-osteolysis was greatly reduced while the heated gloves were on. However, consistent with Park et al, Barb’s acro-osteolysis did not stop despite increased circulation to the digits.5 As a result, Barb’s fingers continued to shorten and impair hand function.

Interestingly, ROM improved in the right wrist, bilateral 2nd digits and left 5th digit. This increase occurred despite no formal stretching or strengthening exercises during the four-month intervention period. Additionally, two surprising outcomes of this study were the improvements in the nine-hole peg test performance and the return of sensation in six digits, especially the left digits. The left 5th digit improved from loss of protective sensation to within normal range. The 2nd digit had a four-year history of ulcers, yet sensation improved in the intervention period from loss of protective sensation to reduced protective sensation (see Table 3).

Conclusion

The promising outcomes in this case warrant further patient-centered research to establish efficacy and optimum parameters for heated glove use. More research is needed to assess the prophylactic potential of prescribing daily, continuous heat earlier in the disease process to perhaps delay the sequelae of dSSc vasculopathy.

Barb controlled for variables through consistent data collection methods, including setting, time frame (11 a.m.), rater and instrumentation. Subject characteristics were controlled; there were no changes in occupation, activities, diet, medication or stress levels. Therefore, future research based on Barb’s design may be feasible to determine benefit and generalizability to the larger scleroderma population.

Read “A Glove By Any Other Name May Give Less Heat,” (The Rheumatologist, November 2017).

Rosemarie Curley, MPT, DPT, completed her transitional doctorate from Northeastern University College of Professional Studies in July and practices physical therapy in inpatient rehabilitation in Richmond, Va. Personal experience with topical steroid withdrawal in children and diffuse systemic sclerosis fuels her desire to research and present the patient’s perspective in evidence-based practice.

Rosemarie Curley, MPT, DPT, completed her transitional doctorate from Northeastern University College of Professional Studies in July and practices physical therapy in inpatient rehabilitation in Richmond, Va. Personal experience with topical steroid withdrawal in children and diffuse systemic sclerosis fuels her desire to research and present the patient’s perspective in evidence-based practice.

Jeananne Elkins, PT, PhD, DPT, MPH, is an advanced fellow in geriatrics at the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Care Center (GRECC) in Atlanta. She is a health services researcher. Her recent work is in evidence-based physical therapy interventions and in medical care–caregiver interactions to improve support of informal caregivers.

Jeananne Elkins, PT, PhD, DPT, MPH, is an advanced fellow in geriatrics at the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Care Center (GRECC) in Atlanta. She is a health services researcher. Her recent work is in evidence-based physical therapy interventions and in medical care–caregiver interactions to improve support of informal caregivers.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial/benefit ties with the gloves described in this article.

References

- Matucci-Cerinic M, Kahaleh B, Wigley FM. Review: Evidence that systemic sclerosis is a vascular disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Aug;65(8):1953–1962.

- Varga J. Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: A prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007 Mar;117(3):557–567.

- Wigley FM Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11;375(6):556–565.

- Merkel PA, Herlyn K, Martin RW, et al. Measuring disease activity and functional status in patients with scleroderma and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Sep;46(9):2410–2420.

- Park JK, Fava A, Carrino J, et al. Association of acroosteolysis with enhanced osteoclastogenesis and higher blood levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Jan;68(1):201–209.

- Robinson DJ, Eisenberg D, Nietert PJ, et al. Systemic sclerosis prevalence and comorbidities in the US, 2001–2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008 Apr;24(4):1157–1166.

- Shah AA, Wigley FM. My approach to the treatment of scleroderma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013 Apr;88(4):377–393.

- Barnes J, Mayes MD. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis: Incidence, prevalence, survival, risk factors, malignancy, and environmental triggers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012 Mar;24(2):165–170.

- Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002.

Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jul;66(7):940–944 - Amanzi L, Braschi F, Fiori G, et al. Digital ulcers in scleroderma: Staging, characteristics and sub-setting through observation of 1614 digital lesions. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Jul;49(7):1374–1382.

- Cappelli L, Wigley FM. Management of Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers in scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015 Aug;41(3):419–438.

- Thombs BD, Jewett LR, Assassi S, et al. New directions for patient-centred care in scleroderma: The Scleroderma Patient-Centred Intervention Network (SPIN). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012 Mar–Apr;30(2 Suppl 71):S23–S29.

- Danieli E, Airo P, Bettoni L, et al. Health-related quality of life measured by the Short Form 36 (SF-36) in systemic sclerosis: Correlations with indexes of disease activity and severity, disability, and depressive symptoms. Clin Rheumatol. 2005 Feb;24(1):48–54.

- Schiopu E, Impens AJ, Phillips K. Digital ischemia in scleroderma spectrum of diseases. Int J Rheumatol. 2010;2010. pii: 923743.

- Hughes M, Herrick AL. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Jan;56(1):14–25.

- Moran ME. Scleroderma and evidence based non-pharmaceutical treatment modalities for digital ulcers: A systematic review. J Wound Care. 2014 Oct;23(10):510–514.

- Brand M, Hollaender R, Rosenberg D, et al. An observational cohort study of patients with newly diagnosed digital ulcer disease secondary to systemic sclerosis registered in the EUSTAR database. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015 Jul–Aug;33(4 Suppl 91):S47–S54.

- Mouthon L, Carpentier PH, Lok C, et al. Ischemic digital ulcers affect hand disability and pain in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2014 Jul;41(7):1317–1323.

- Magee DJ. Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2008.

- Young A, Namas R, Dodge C, Khanna D. Hand impairment in systemic sclerosis: Various manifestations and currently available treatment. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2016;2(3):252–269.

- Tresolini C, the Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. San Francisco: 1994.

- Hudson M, Thombs BD, Steele R, et al. Health-related quality of life in systemic sclerosis: A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Aug 15;61(8):1112–1120.

- Askew LJ, Beckett VL, An KN, Chao EY. Objective evaluation of hand function in scleroderma patients to assess effectiveness of physical therapy. Br J Rheumatol. 1983 Nov;22(4):224–232.

- Mancuso T, Poole JL. The effect of paraffin and exercise on hand function in persons with scleroderma: A series of single case studies. J Hand Ther. 2009 Jan–Mar;22(1):71–77, quiz 78.

- Nasir SH, Troynikov O, Massy-Westropp N. Therapy gloves for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2014 Dec;6(6):226–237.

- Stefanantoni K, Sciarra I, Iannace N, et al. Occupational therapy integrated with a self-administered stretching program on systemic sclerosis patients with hand involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 Sep–Oct;34 Suppl 100(5):157–161.

- Vannajak K, Boonprakob Y, Eungpinichpong W, et al. The short-term effect of gloving in combination with traditional Thai massage, heat, and stretching exercise to improve hand mobility in scleroderma patients. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2014 Jan;5(1):50–55.

- Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV, et al. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014 Oct 15;312(15):1513–1514.

- Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurment in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993 Nov;55(2):195–203.

- Leung YY, Ho KW, Zhu TY, et al. Construct validity of the modified numeric rating scale of patient global assessment in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012 Apr;39(4):844–848.

- Rehab measures: Numeric pain rating scale. 1995; reviewed 2013 Jan 17.

- Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003 Apr;10(4):390–392.

- Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain scale. Pain. 2001 Nov;94(2):149–158.

- Mathiowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, et al. Grip and pinch strength: Normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985 Feb;66(2):69–74.

- Mathiowetz V. Comparison of Roylan and Jamar dynamometers for measuring grip strength. Occup Ther Int. 2002;9(3):201–209.

- Norkin CC, White DJ. Measurement of Joint Motion: A Guide to Goniometry, 5th ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 1985.

- Lewis E, Fors L, Tharion WJ. Interrater and intrarater reliability of finger goniometric measurements. Am J Occup Ther. 2010 Jul–Aug;64(4):555–561.

- Uddin Z, MacDermid JC, Ham HH. Test–retest reliability and validity of normative cut-offs of the two devices measuring touch threshold: West Enhanced Sensory Test and Pressure-Specified Sensory Device. Hand Therapy. 2014;9(14).

- Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Kashman N, Volland G. Adult norms for the nine-hole peg test of finger dexterity. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 1985;5(1):24–38.

- Wang YC, Magasi SR, Bohannon RW, et al. Assessing dexterity function: a comparison of two alternatives for the NIH Toolbox. J Hand Ther. 2011 Oct–Dec;24(4):313–320.

- Sandqvist G, Eklund M. Hand Mobility in Scleroderma (HAMIS) test: The reliability of a novel hand function test. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Dec;13(6):369–374.

- Sandqvist G, Eklund M. Validity of HAMIS: A test of hand mobility in scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Dec;13(6):382–387.

- Lefevre-Colau MM, Poiraudeau S, Oberlin C, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the modified Kapandji index for assessment of functional mobility of the rheumatoid hand. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Jul;84(7):1032–1038.