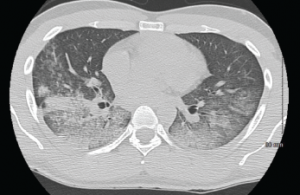

A CT scan of the chest showing multifocal ground-glass opacities, representative of hemorrhage, with numerous nodular interstitial opacities primarily within a peribronchovascular distribution.

A 22-year-old Indian male presented to the emergency department with hemoptysis. A month prior, he had presented to an urgent care center complaining of cough with occasional episodes of blood-tinged sputum in the morning. He was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia based on a chest X-ray without laboratory testing and was prescribed levofloxacin.

A few days later, he called his primary care physician for bilateral ankle pain and was told that this could be due to fluoroquinolone-induced tendinitis. The ankle pain, as well as his cough, varied in intensity before he presented to the hospital, and during this interval he also noted bilateral knee, wrist and right elbow pain. He also noted that his eyes had been “bloodshot” recently, but denied visual changes or eye pain.

The day prior to his presentation at our hospital, he noted an acute worsening of his cough with more frequent hemoptysis and new dyspnea. His primary care physician ordered a chest X-ray that was suggestive of worsening multifocal pneumonia.

On admission, the patient did not report any fevers, weight loss, night sweats, rash, dysuria, bloody stools, diarrhea or lymphadenopathy. He denied sexual activity, smoking and illicit drug use. He was not taking any medications other than acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. His only travel had been to Texas a year earlier for mountain climbing, and he denied any recent sick contacts or any incarceration.

His vitals: blood pressure 114/84 mmHg; heart rate 116 beats/minute; temperature 97.5º F; respiratory rate 16 per minute; oxygen saturation 90% on room air, which improved to 98% on 2L O2 via nasal cannula. His complete blood count revealed a hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL, WBC of 10,000 without bands, platelets of 301,000. His electrolytes, as well as renal and hepatic function, were within normal limits. ESR and CRP were 82 mm/hr and 144 mg/dL, respectively. Urinalysis was notable for 2+ blood with 11–20 RBCs/hpf without casts. A chest X-ray showed multifocal opacities, most pronounced in the right upper lobe. The cardiopulmonary exam was significant for tachycardia, with regular rhythm and bilateral rales. Bilateral conjunctival injection was noted, with a normal nasopharyngeal exam. The musculoskeletal exam revealed periarticular tenderness of the knees and wrists bilaterally, and pain with active and passive flexion of the right elbow, and tenderness to palpation of the right posterior ankle. No rash was visualized.

The following day, the patient underwent a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Toward the end of the procedure, he developed respiratory distress with significant oxygen desaturation, requiring intubation. The BAL fluid was grossly bloody with a marked elevation of RBCs and WBCs with a neutrophil predominance. There were alveolar macrophages, blood, and acute and chronic inflammatory cells consistent with the diagnosis of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH).

It’s not unusual for DAH to be the initial manifestation of certain autoimmune and connective tissue diseases, and it’s responsible for many rheumatology consultation requests. DAH is caused by destruction of the alveolar basement membrane or the alveolar capillaries themselves (capillaritis), resulting in accumulation of red blood cells in the alveoli. Clinically, this can lead to hemoptysis, hypoxia, anemia and pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray, which can be mistaken for pneumonia.

Pulmonary capillaritis can be isolated to the lung or be a part of a systemic vasculitis, the latter of which can also involve large pulmonary blood vessels. Hemoptysis can be an insidious process or a dramatic presentation causing rapid clinical deterioration. Importantly, hemoptysis can be absent in up to one-third of patients with DAH, and any hemoptysis should be considered potentially life threatening.1

Differential Diagnosis

This patient presented with a multisystem disease process, making the differential diagnosis broad. Based on his elevated ESR and CRP, we know the underlying cause is likely inflammatory or infectious. The biggest clue that vastly narrows the possible causes is hemoptysis in an otherwise healthy patient with no history of lung disease. The major diseases that should be considered include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (eGPA), Goodpasture’s syndrome (GS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and various infectious etiologies, including tuberculosis. Other less common diseases include isolated pulmonary capillaritis, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, Behçet’s syndrome, leptospirosis and mixed connective tissue disease.

The Case Continued

A CT scan of the chest showed a right, upper lobe predominant, nodular opacification with central cavitation, with diffuse ground-glass opacities without pleural effusions. Serologic studies revealed negative influenza and blood cultures, and normal C3 and C4 complement levels. Anti-streptolysin and anti-GBM antibodies were negative. Atypical and perinuclear p-ANCA titers <1:20, c-ANCA 1:320, with negative ANA, anti-dsDNA, and anti-Smith antibodies were shown. HIV testing was negative.

BAL fluid analysis was negative for acid-fast bacilli, viruses, fungi, as well as malignant cells. Following bronchoscopy, the patient was given daily methylprednisolone 1,000 mg for three days, reduced to 80 mg daily for a week, and transitioned to oral prednisone 60 mg per day. Rituximab infusion was started on Day 5 after initiation of immunosuppression, dosed at 600 mg weekly for four weeks. His condition improved dramatically over the next few days, with successful extubation and vastly improved infiltrates on chest X-ray. He developed hoarseness, prompting an ENT evaluation that revealed bilateral vocal process granulomas (contact granulomas). He was discharged on 60 mg prednisone daily with weekly 600 mg rituximab infusions. A presumptive diagnosis of GPA was made, and a definitive diagnosis made after all laboratory results were available some time later.

What Is GPA?

GPA is a rare type of primary vasculitis. The mean age at time of diagnosis is 41 years, and without treatment, mean survival time is less than one year. The presentation and clinical course are variable, ranging from mild disease involving only the upper respiratory tract (i.e., sinuses) to life-threatening involvement causing pulmonary hemorrhage and/or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (GN). There is a strong association with c-ANCA and anti-proteinase 3 antibodies.2

GPA was previously described as limited or generalized, with the latter comprising about 10% of cases. Limited GPA referred to all patients without renal involvement, often presenting with granulomas without vasculitis. More recently, this classification has become less popular, because limited disease could still be life threatening, such as in our patient’s case. Instead, it is useful to think of the disease as part of a spectrum—with localized disease that can progress to early systemic involvement, followed by generalized disease with imminent organ failure (organ threatening) and, eventually, severe disease that becomes life threatening. The clinical diagnosis should ideally be confirmed with a biopsy of the kidneys, skin or lungs (thoracoscopically). Transbronchial lung and nasal biopsies are typically unhelpful.3

Constitutional symptoms are often present, including fever, weight loss, fatigue, and malaise. Skin and musculoskeletal involvement commonly affects patients at some point, manifesting as palpable purpura, ulcers, nodules and arthralgia/myalgia usually in the absence of synovitis. Eye involvement is common and can sometimes be the initial presentation. Proptosis affects approximately 15% of patients, and there can be scleritis, episcleritis, uveitis and conjunctivitis.

Approximately half of all patients present with chronic sinusitis, with chronic inflammation present in the nasal mucosa. This can lead to purulent discharge, ulceration or granulomas of the mucosa, as well as septal perforation and nasal cartilage destruction. Stridor is the most worrisome sign of upper airway involvement.3

Approximately half of all patients present initially with pulmonary involvement, although many of these patients are asymptomatic despite positive chest X-ray findings. Renal disease affects about 15–30% of GPA patients on presentation—and eventually affects a majority. Very mild cases—such as in our patient—can present with minimal involvement, such as isolated hematuria and/or proteinuria, while others can have asymptomatic GN with proteinuria, pyuria and hematuria with casts. More severe cases can present with a pauci-immune, crescentic GN. Large vessel renal vasculitis and granulomas are extremely uncommon.4,5

How can we distinguish between the diseases in our differential diagnosis? In addition to the pulmonary involvement described thus far, the clinical entities described above are also known for their renal involvement. After an initial diagnostic workup, our patient’s differential was narrowed to the pulmonary-renal syndromes, a term describing the clinical entities that commonly cause diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis.

The three major causes are: 1) ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV) (e.g., GPA, MPA, EGPA; 2) anti-glomerular basement antibody disease (e.g., GS); and 3) SLE.5 The final diagnosis relies on the specific pattern of clinical, serologic, pathologic and radiographic features. Although serologic testing can help, the turnaround time for some tests, such as ANCA, can be three to seven days, which makes it important to make a presumptive clinical diagnosis.

The most sensitive serologic test is anti-GBM antibodies (95% sensitive for GS). These antibodies are directed against type IV collagen—the major component of basement membranes—and their presence in the setting of hemoptysis and/or glomerulonephritis is enough to make the diagnosis of GS. ANCA testing is still warranted because although ANCA positivity certainly suggests GPA/MPA/EGPA, between 10% and 40% of GS patients are also ANCA positive (particularly p-ANCA).6,7 Thus, it’s possible, although not common, for a patient with GS to be anti-GBM negative and ANCA positive. By the same token, 10–20% of patients with GPA/MPA/EGPA can be ANCA negative, making the clinical features and biopsy more important for diagnosis.7

Among the ANCA-associated vasculitides, GPA and MPA have the most similarities in presentation. MPA does not affect the upper airways, but is more likely to cause DAH, and it lacks ocular involvement. EGPA has more distinct features—asthma, peripheral eosinophilia and gastrointestinal involvement—that allow it to be differentiated from the other diseases.

Unlike the other entities, GS does not usually present with systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, arthralgias and rash. It should be noted that it is also rare for GS to have a predominantly pulmonary involvement. GS is rarer than the other diseases, although it is the most likely of the aforementioned diseases to affect a young patient such as ours.6

Because eye involvement occurs with the AAV (particularly GPA) and SLE, our patient’s conjunctivitis made Goodpasture’s less likely. Reduced complement levels are unique to SLE in our differential, but because complement levels reflect a balance of complement production and consumption, normal levels cannot always exclude SLE.

Treatment Options

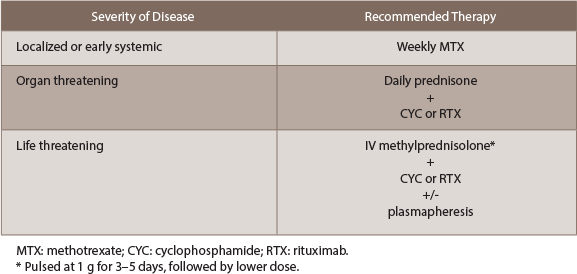

The approach to all ANCA-associated vasculitides relies on corticosteroids in combination with other immunosuppressants or, rarely, plasmapheresis. Treatment can be divided into induction therapy and maintenance therapy. The aggressiveness of induction therapy depends on disease severity. Patients receiving both induction and maintenance therapy are immunosuppressed and, thus, are at risk for opportunistic infections. Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci is advised for those patients receiving greater than 15 mg prednisone per day (or equivalent). Nasal irrigation with 2% mupirocin can help prevent sinus infections.

Induction therapy (see Table 1): For localized or early-systemic disease without imminent organ failure, daily prednisone with the addition of weekly methotrexate is an effective option that offers the least number of side effects. If methotrexate is contraindicated, rituximab can be used instead. These patients typically do very well, and although a steroid taper is warranted, caution must be used during the first month given the high risk of relapse.

For disease that is organ threatening, daily prednisone with the addition of either cyclophosphamide (CYC) or rituximab (RTX) is recommended. This recommendation is based on the RAVE trial, which found RTX to be noninferior to CYC. CYC can be given as either a monthly IV pulse or a daily dose, the latter offering less risk for relapse at the expense of side effects.8 With CYC, the absolute neutrophil count should be kept >1000/μL. Rituximab can be given as a weekly dose of 375 mg/m2 over four weeks or a 1,000 mg biweekly dose over two weeks. Before starting rituximab, it is imperative to test patients for hepatitis B and tuberculosis.

Patients with life-threatening disease benefit from the addition of plasmapheresis to dual corticosteroid and CYC/rituximab therapy (see MEPEX trial9). Intravenous methylprednisolone should be started immediately, at a pulse dose of 1 gram for three to five days, followed by a lower dose. If a patient is receiving both rituximab and plasmapheresis, it’s important to perform plasmapheresis first, because a portion of rituximab will be removed. The major indications for plasmapheresis are: 1) advanced kidney disease (requiring hemodialysis, creatinine >4 mg/dL or rapidly declining function); 2) positive anti-GBM antibodies; and 3) pulmonary hemorrhage.8

Maintenance therapy: Once remission is achieved, the goal is to step down therapy to medications that are less toxic. If remission is not reached within six months, this should be considered as induction failure and the regimen should be changed; for example, the RAVE trial found rituximab was superior to CYC in relapsing AAV.9 The typical maintenance regimen typically consists for low-dose prednisone in combination with another immunosuppressant, such as azathioprine (AZT), methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or leflunomide (LEF).8

We still have much to learn about the role of these medications. Throughout maintenance therapy, an attempt should be made to taper the prednisone dose as much as possible. The IMPROVE trial suggests that AZT is most effective in maintaining remission (dosed at 2 mg/kg/day), particularly in generalized disease.9 If rituximab were used to achieve disease remission, AZT can be attempted as maintenance, although the MAINRITSAN trial9 found 500 mg of rituximab every six months to be more effective.

The ongoing RITAZAREM trial9 aims to assess the effect of periodic rituximab infusions in addition to maintenance with AZT or methotrexate.

If maintenance therapy fails and remission occurs, induction therapy should be repeated and the subsequent maintenance regimen should be intensified.

Payam Pourhassani, DO, MSc, is a third-year internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia. He received his medical degree from Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Payam Pourhassani, DO, MSc, is a third-year internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia. He received his medical degree from Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Sneha N. Patel, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia. She received her medical degree from St. George’s University in 2015.

Sneha N. Patel, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Drexel University College of Medicine/Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia. She received her medical degree from St. George’s University in 2015.

Arundathi Jayatilleke, MD, is the program director of the Drexel Rheumatology Fellowship at Drexel University. Dr. Jayatilleke completed her internal medicine residency at New York Presbyterian Hospital and her rheumatology fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery.

Arundathi Jayatilleke, MD, is the program director of the Drexel Rheumatology Fellowship at Drexel University. Dr. Jayatilleke completed her internal medicine residency at New York Presbyterian Hospital and her rheumatology fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery.

References

- Lara AR, Schwarz MI. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Chest. 2010 May;137(5):1164–1171.

- Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet. 2006 Jul 29;368(9533):404–418.

- Kallenberg CG. Key advances in the clinical approach to ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014 Aug;10(8):484–493.

- Lee RW, D’Cruz DP. Pulmonary renal vasculitis syndromes. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Aug;9(10):657–660.

- Kimmel M, Braun N, Alscher MD. “Differential diagnosis of the pulmonary-renal syndrome.” An Update on Glomerulopathies—Clinical and Treatment Aspects (Prabhakar S, ed.). Rijeka, Croatia: InTech, 2011 Nov.

- Pusey CD. Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Kidney Int. 2003 Oct;64(4):1535–1550.

- Saxena R, Bygren P, Arvastson B, Wieslander J. Circulating autoantibodies as serological markers in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary renal syndrome. J Intern Med. 1995 Aug;238(2):143–152.

- Holle JU, Gross WL. Treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV). Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(4):483–486.

- Geetha D, Kallenberg C, Stone JH, et al. Current therapy of granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis: The role of rituximab. J Nephrol. 2015 Feb;28(1):17–27.