Although HIV testing may seem outside our scope of practice as rheumatologists, it’s important to consider incorporating it into your screening procedures, along with tests for hepatitis B and C.

Image Credit: Africa Studio/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

It has been nearly 35 years since the original descriptions of what now is recognized as AIDS (the acquired immune deficiency syndrome), an advanced form of infection secondary to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The epidemic of HIV infection remains the singular most dramatic epidemic of our generation and will likely remain with us for generations to come.

The disease itself (i.e., HIV infection) has been transformed from a highly fatal illness with a progressive course and no known therapy to a complex but manageable disease for those with access to antiviral therapy. Socially, the epidemic of HIV infection has changed from one of high visibility attended by fear and stigmatization to one that now has lost much of its exclusivity, affecting all segments of the population to some degree, albeit disproportionally.

Management of HIV infection requires the participation of virtually all specialists to attend to its complications and comorbidities. An important question for the rheumatology community is: What is our current role and responsibility in caring for the nearly 1 million infected patients living today, some of whom will need our services in the years to come?

Our review approaches this question in three parts. The first section reviews the transformation of HIV infection from a devastating immunodeficiency to a chronic inflammatory disease with remarkable symmetry to several connective tissue diseases. The second discusses the dramatic deceleration of HIV-associated autoinflammatory manifestations and the emergence of a new set of rheumatic morbidities. The final section focuses on four areas that we believe rheumatologists and advanced practitioners in rheumatology need to be aware of to be in a position to provide optimal care.

From Immunodeficiency to Chronic Inflammatory Disease

On June 5, 1981, an account appeared in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report describing five men from the Los Angeles area with a previously undescribed immunodeficiency. This marked the recorded beginning of the AIDS epidemic. Many clinicians and researchers suspected that AIDS had an infectious etiology, but it took until 1983 for the discovery of the virus.1

In retrospect, we can now view this epidemic as having three phases, beginning with its presentation as a devastating immunodeficiency in which individuals, often homosexual men or intravenous drug users, developed serious and multiple opportunistic infections. These infections were often treatable, such as pneumocystis pneumonia (caused by p. jirovecii, formerly known as p. carinii), serious mycobacterial and fungal infections, as well as opportunistic malignancies, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Such a constellation had not been previously described in otherwise healthy individuals, and this phase, lasting roughly through the end of the first decade of AIDS, could be considered the era of morbidity and mortality due to treatable opportunistic infections.

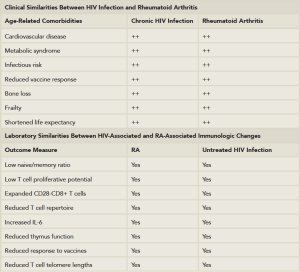

One striking area of clinical similarity between HIV infection and RA is the aaccelerated cardiovascular disease.

A second recognizable phase of the epidemic evolved when both diagnosis and management had greatly improved to the point at which patients were recognized earlier and afforded antimicrobial prophylaxis for many of these opportunistic infections (e.g., SMZ-TMP to prevent PJP). During this phase, which may be viewed as the era of morbidity and mortality due to untreatable opportunistic complications, patients succumbed to those complications having either no effective therapy, such as progressive KS and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, or profoundly challenging infections to treat, such as disseminated CMV and other pathogens. Without effective antiviral therapy, which at the time was limited to only a few drugs, the prognosis for the infected population was grim, and by 1993, AIDS was the leading cause of death among people age 25–44.1

Starting in 1996, new classes of antiretroviral agents became increasingly available and ushered in the era that we now know as combination antiretroviral therapy or cART (also known as highly active antiretroviral therapy or HAART). By 1997, the mortality of HIV disease had plummeted and currently has been surpassed by hepatitis C infection.2

The third phase or epoch of the HIV epidemic has progressively arisen as a result of advanced care on multiple fronts, leading to durable and perhaps lifelong viral suppression. Thus, in 2015, we rarely see treatable or untreatable opportunistic infections; however, we are formidably challenged with the sequelae of persistent immune activation. As a result, an aging HIV infected population has emerged, with an estimated one-fifth of the currently estimated 1.1 million infected U.S. patients being over the age of 55.3

Attendant to this new longevity has been the development of a number of seemingly non-AIDS-related complications, including cardiovascular disease, bone disease, sarcopenia and neurologic disease.4 These observations have led to growing concern that HIV-infected patients are experiencing premature aging and that chronic immune dysfunction, immune activation and inflammation predict and likely contribute to this excess morbidity and mortality.5,6

This concern is similar to a general concern held by practitioners who treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA); one striking area of clinical similarity between HIV infection and RA is the excess mortality from accelerated cardiovascular disease. Although the rheumatology community is well familiar with the increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in RA, rheumatologists are less familiar with the similar situation with HIV.

(Click for larger image)

Table 1: Clinical and Laboratory Similarities Between HIV Disease & Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Adapted from: Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2011. 62:141–155; and Weyand et al. T-cell aging in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014 Jan; 26(1):93–100.

In HIV infection, as in RA, there is an increase of at least 50% in the relative risk for myocardial infarction when compared with well-matched controls.6,7 The relationship between these events and a persistent inflammatory state has been extensively reviewed and is not dissimilar to RA.6 Table 1 describes the potential clinical and immunologic similarities between HIV infections and RA.

Two trials demonstrate the symmetries between HIV infection and autoimmune disease: one examining the safety and effectiveness of low-dose methotrexate at reducing inflammation in adults on effective antiviral therapy and another examining the safety and potential efficacy of tocilizumab to reverse the adverse effects of persistent HIV associated immune activation in patients who have well-controlled viral infection. The future holds promise that there may be lessons learned from each field that may benefit the other.

Changing Spectrum of Rheumatic Diseases in HIV Infection in the cART Era

After the first several years of the HIV epidemic, the rheumatology community became focused on nosologically distinct rheumatic manifestations, in large part due to the seminal report by Winchester and colleagues from New York City on 13 infected individuals with severe oligoarticular arthritis with attendant features that we would now recognize as reactive arthritis.8 Because New York was among the epicenters of the epidemic, it took considerable time for rheumatologists in low-incidence areas to fully appreciate these dramatic complications.

Although debate took place regarding the epidemiology and significance of these rheumatic manifestations, they clearly were distinct in many ways: they included an array of conditions, some of which were previously unrecognized, such as painful articular syndrome, HIV arthritis and the diffuse lymphocytosis syndrome (DILS). Other inflammatory diseases were also recognized, some of which, at times, were found to have distinctive features; these included reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathy and other myopathic diseases and vasculitis, all of which have been extensively reviewed.9,10,11

With the ushering in of the era of cART and the dramatic shift in the clinical epidemiology of HIV disease, a remarkable deceleration of these inflammatory rheumatic complications occurred.11,12 Today, despite the prolongation of life and an aging HIV-infected population, newly trained rheumatologists see few such cases.

In place of those rheumatic complications previously described in patients with advanced disease, a new array of rheumatic disorders have emerged; in addition, a growing number of aging HIV-infected patients appear to have comorbid de novo rheumatic conditions, covering the gamut of systemic autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, posing new clinical challenges. Three disorders deserve special attention at present: avascular necrosis, osteoporosis and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Avascular Necrosis

Over the past decade, the incidence of avascular necrosis of bone in the HIV-infected population appears to be rising and may be as high as 0.3–3.4/1,000 person years compared with the general population, in which the incidence is estimated at 0.03–0.04/1,000 person years.13 A small study in asymptomatic HIV-infected men based on screening MRI revealed a prevalence of 4.4% in the HIV-positive men and 0% in corresponding uninfected controls.14

The etiology of this complication is poorly understood, with conflicting data on a number of disease- and treatment-related variables, including the length of exposure to and class of ART, CD4 nadir, presence of hyperlipidemia and history of glucocorticoid use. Regardless, awareness of this complication is now essential in the context of evaluating bone and joint pain in HIV-infected individuals.

Osteoporosis

A substantial body of data now exists to support that low bone density is more prevalent in HIV-positive individuals compared with HIV-negative controls.13 A number of factors, both traditional and disease related, may contribute to bone loss, including the use of certain ARTs, especially in the first few years of therapy.13,15 A loss of 2–6% of bone mineral density has been observed over the first two years of therapy comparable to losses observed in the first two years of menopause in a typical HIV-negative population.15

A recent expert panel on bone disease in HIV infection suggests that HIV should be considered a risk factor for bone loss. Further, they recommend screening for fragility in all HIV-infected postmenopausal women and all infected men older than 50 years.15 While limited, there are data demonstrating effectiveness of bisphosphonates; in contrast, there is no clear evidence that vitamin D replenishment is effective.13,15 A clinical algorithm has been recently proposed.15

Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS)

IRIS is a complication of great interest and clinical importance in HIV infection and refers to a condition most frequently observed in patients with advanced HIV who experience paradoxical worsening of preexisting infectious processes following the initiation of cART.16 Preexisting infections in individuals with IRIS may have been previously diagnosed and treated, or they may be subclinical and later unmasked by the host’s regained capacity to mount an inflammatory response.

In addition to IRIS reactions from occult infections, paradoxical inflammatory reactions can occur, heralding exacerbations of previous occult or quiescent autoinflammatory disease or the appearance of a new one.12,17

IRIS reactions resembling RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, autoimmune thyroid disease and other conditions have all been described.

This disorder is generally self-limited, and management is generally conservative. However, extreme examples requiring immunosuppression have been reported.

4 Things Rheumatologists Need to Know

- Conduct HIV testing in the rheumatology office. Although HIV testing may seem outside our spectrum of practice as rheumatologists, we are convinced it is logical and should be incorporated into screening procedures.Rheumatologists already screen for hepatitis B and C in an extended and increasing range of settings. HIV is epidemiologically linked to both of these bloodborne viruses and, thus, could easily be included in a screening panel whenever hepatitis B and C are tested for. Further, the CDC recommends that healthcare providers test everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 at least once as part of routine healthcare and indicates that pretest counseling is not necessary; patients must merely be informed so they may opt out.18,20,15 We prefer language along the lines of: “We are going to screen you for a number of infections, including hepatitis B and C and HIV as part of this evaluation.” As a result, we have virtually never had a patient refuse; occasionally, patients will relate to us that they have already been tested.

- Be aware of safety issues when using immunosuppressives, including biologics, in HIV-infected patients with serious rheumatic comorbidities.

The treatment of any patient with a systemic inflammatory rheumatic disorder with a chronic infection is indeed a setting that should give us pause, because virtually all of our therapies may compromise the integrated immune response. Although systemic inflammatory disorders in the setting of HIV are rare, occasionally such patients may require immunosuppression. Rheumatologists may draw on a formidable experience from the transplantation world demonstrating that intense and prolonged immunosuppression may be well tolerated, if the patient has a well-controlled viral load and maintains a CD4 cell count above 200 cells per cubic milliliter.19 Further, although there are no prospective trials examining the safety of biologics, case reports and small series suggest that biologics, especially TNF inhibitors, may be safe in similar settings.20 Whenever HIV patients with rheumatic comorbidities are managed, it should be done in close cooperation with an engaged HIV practitioner. - Continue learning about the new and emerging rheumatic complications of HIV infection.

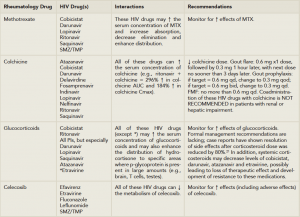

In the article above, we described the emergence of AVN, osteoporosis and IRIS as complications of special interest. New complications and disorders will no doubt evolve in the future. - Be aware of and screen for critical drug–drug interactions in the treatment of HIV-associated rheumatic diseases. With an aging HIV-infected population, an increasing number of HIV-infected patients will inevitably develop the gamut of routine rheumatic problems, ranging from gout to local/regional disorders of tendonitis, bursitis, etc. The treatment of HIV infections is now extraordinarily complicated from a pharmacologic perspective and has outstripped the capacity for even most infectious disease specialists who don’t emphasize HIV in their practice.Currently, five classes of drugs are used to treat HIV. The five classes are nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), entry inhibitors and integrase inhibitors.Complicating matters further is that some of the medications (several PIs and one integrase inhibitor) require “boosting” with either ritonavir or cobicistat. Many PIs and both boosters have clinically significant interactions with several medications commonly used in rheumatology (see Table 2). Perhaps the most significant interaction for the practice of rheumatology is that between glucocorticoids and protease inhibitors (especially darunavir, lopinavir, saquinavir), as well as both pharmacologic boosters (ritonavir and cobicistat); all of these HIV medications are potent modulators of the cytochrome P450 enzyme systems, with ritonavir being the most potent. Cobicistat is a relatively new pharmacologic booster as well, one for which there are relatively few data on its interaction with glucocorticoids, although similar effects are highly likely.

(Click for larger image)

Table 2: Important Rheumatology/HIV Drug-Drug Interactions.

Source: Lexicomp Online, Interactions, Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp Inc.; March 12, 2015Numerous glucocorticoids use CYP3A4 as their major route of metabolism and, thus, are vulnerable to profound pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic fluctuations in the presence of these HIV drugs. The frequency and magnitude of these drug–drug interactions with glucocorticoids as a class are not well known, regardless of the route of administration (e.g., oral, intra or periarticular, inhaled as well as other routes).

For rheumatologists and advanced practitioners in rheumatology, extreme caution should be exercised when using glucocorticoids in patients on these HIV drugs. The situation appears most critical for our specialty with regard to the interaction of ritonavir and/or protease inhibitors with the administration of intrarticular or soft tissue triamcinolone, which has been reported to induce an iatrogenic hypercortisolism within a few weeks, as well as secondary adrenal insufficiency following a single injection. These cases have recently been reviewed.22 For oral administration of prednisone or prednisolone, no formal recommendations have been made for dose adjustment, although at the minimum, extreme caution should be exercised with their use (see Table 2). Most importantly, if new medications are contemplated in a patient with HIV infection already on therapy, a specific discussion about the possible ramifications should be had with the HIV caregiver.

In 2015, we rarely see treatable or untreatable opportunistic infections [in AIDS patients]; however, we are formidably challenged with the sequelae of persistent immune activation.

Summary & Conclusion

The epidemic of HIV infection will be with us all for the rest of our professional lives. With the increased life expectancy of the HIV population, rheumatologists and advanced practioners will be called upon to see both directly related and incidental rheumatic disorders. Rheumatologists need to incorporate screening and diagnostic HIV testing into their practices and be capable of diagnosing HIV-related disorders. Finally, when managing HIV-infected patients with rheumatic disorders, rheumatologists and advanced rheumatology practioners need to be able to treat both effectively and safely, with the armamentarium of antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs.

Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, is professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, Ohio; the RJ Fasenmyer Chair of Clinical Immunology; the Theodore F. Classen, DO, Chair of Osteopathic Research and Education; and vice chairman of the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases.

Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, is professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, Ohio; the RJ Fasenmyer Chair of Clinical Immunology; the Theodore F. Classen, DO, Chair of Osteopathic Research and Education; and vice chairman of the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases.

Elizabeth Kirchner, MSN, CNP, is director of patient care for the R.J. Fasenmyer Center for Clinical Immunology and has been a nurse practitioner for 15 years in the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

Elizabeth Kirchner, MSN, CNP, is director of patient care for the R.J. Fasenmyer Center for Clinical Immunology and has been a nurse practitioner for 15 years in the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

References

- Kallings LO. The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS. J Intern Med. 2008 Mar;263(3):218–243.

- Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al. Closing the gap: Increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81355.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among older Americans. 2013.

- Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:141–155.

- Weyand CM, Yang Z, Goronzy JJ. T-cell aging in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Jan;26(1):93–100.

- Hunt PW. HIV and inflammation: Mechanisms and consequences. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012 Jun;9(2):139–147.

- Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM 3rd, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2013 Oct;166(4):622–628.e1.

- Winchester R, Bernstein DH, Fischer HD, et al. The co-occurence of Reiter’s syndrome and acquired immunodeficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Jan;106(1):19–26.

- Lawson E, Bond K, Churchill D, et al. A case of immune reconstitution syndrome: Adult-onset Still’s disease in a patient with HIV infection. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Apr;48(4):446–447.

- Patel N, Patel N, Espinoza LR. HIV infection and rheumatic diseases: The changing spectrum of clinical enigma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009 Feb;35(1):139–161.

- Nguyen BY, Reveille JD. Rheumatic manifestations associated with HIV in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009 Jul;21(4):404–410.

- Calabrese LH, Kirchner E, Shrestha R. Rheumatic complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: Emergence of a new syndrome of immune reconstitution and changing patterns of disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Dec;35(3):166–174.

- Gedmintas L, Solomon DH. HIV and its effects on bone: A primer for rheumatologists. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012 Sep;24(5):567–575.

- Miller KD, Masur H, Jones EC, et al. High prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in HIV-infected adults. [Authors’ note: See comments.] Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jul 2;137(1):17–25.

- McComsey GA, Tebas P, Shane E, et al. Bone disease in HIV infection: A practical review and recommendations for HIV care providers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51(8):937–946.

- French MA. HIV/AIDS: Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: A reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan 1;48(1):101–107.

- Iordache L, Launay O, Bouchaud O, et al. Autoimmune diseases in HIV-infected patients: 52 cases and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Aug;13(8):850–857.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report., 2006 Sep 22;55(RR14):1–17.

- Harbell J, Terrault NA, Stock P. Solid organ transplants in HIV-infected patients. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013 Sep;10(3):217–225.

- Cepeda EJ, Williams FM, Ishimori ML, et al. The use of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in HIV-positive individuals with rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 May;67(5):710–712.

- Johnson SR, Marion AA, Vrchoticky T, Emmanuel PJ, Lujan-Zilbermann J. Cushing syndrome with secondary adrenal insufficiency from concomitant therapy with ritonavir and fluticasone. J Pediatr. 2006 Mar;148(3):386–388.

- Hall JJ, Hughes CA, Foisy MM, Houston S, Shafran S. Iatrogenic Cushing syndrome after intra-articular triamcinolone in a patient receiving ritonavir-boosted darunavir. Int J STD AIDS. 2013 Sep;24(9):748–752. Doi: 10.1177/09564462413480723.