It’s disheartening to stand by and watch helplessly as your patient dies a slow, painful death. In spring 1990, I had the misfortune of living through such a distressing experience.

Strange happenings in New Mexico & Japan

Ellen was a bookkeeper in her late 40s, living quietly in suburban Boston. For years, she hid a dark secret from her family, her alcohol abuse. Every day, she would deal with the daily stresses of life by consuming copious quantities of liquor. After several failed efforts, she finally succeeded in quitting her drinking. Being sober felt great, but Ellen could not cope with the insomnia that her abstinence seemed to induce. She just could not sleep. A benzodiazepine prescribed by her doctor allowed her to sleep soundly again, but one day it dawned on her that she was becoming addicted to the drug.

Determined to kick this new habit, she began seeing a psychiatrist who recommended a “safe and natural remedy” for her to use as a sleep aid. It sure seemed to work. Each night, after taking one of these tan-colored pills, she would doze off quickly and awaken in the morning feeling refreshed. Best of all, this pill was just a supplement—totally safe and no prescription required.

Rheumatologists must ensure they ask about dietary supplements, not just medications, because patients often won’t think to volunteer that information.

Image Credit: Pressmaster/shutterstock.com

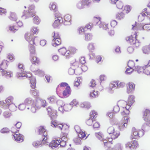

Ellen felt fine and her life returned to normal. Then, out of the blue, she began a slow descent into misery. First, she noticed an odd, eerie feeling; she felt stiff—very stiff actually, as though her entire body was becoming encased in concrete. She visited her primary care doctor, who was baffled. A rheumatologist raised the possibility of systemic sclerosis, but the absence of Raynaud’s phenomenon made this diagnosis suspect. Then came the pain. Ellen was plagued by debilitating myalgia and an unrelenting stabbing sensation in her extremities that a neurologist surmised was due to a rapidly developing polyneuropathy. The million-dollar workup she underwent yielded few helpful clues, except for an unexplained peripheral eosinophilia (see “Eosinophilia: A Practical Guide for the Rheumatologist,” p. 1). In fact, she seemed to be harboring eosinophils everywhere: her blood, her bone marrow and scattered throughout her cement-like soft tissues.

By the time Ellen appeared in our clinic, the cause of her illness had been unmasked. Several months earlier, in October 1989, the New Mexico Department of Health and Environment was notified of three previously healthy women who developed marked peripheral eosinophilia and incapacitating myalgia. All had been consuming oral preparations of the amino acid L-tryptophan (LT), Ellen’s miracle sleep aid.1