Even though these women had undergone extensive clinical evaluation and testing, their illnesses were inconsistent with any known condition that would typically be listed on the lengthy differential diagnosis of eosinophilia. An astute epidemiologist spotted a potential relationship to the notorious toxic oil syndrome that had devastated parts of Spain just a few years earlier.2

At the time of Ellen’s diagnosis of eosinophilia myalgia syndrome (EMS), approximately 1,000 cases had been reported. Although the vast majority of patients experienced an improvement or at least a stabilization of their symptoms following cessation of their use of LT, Ellen was one of the unlucky few whose illness spiraled into a slow death march. Her symptoms over the final months of her life resembled those observed in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. She could no longer move, feed herself or even swallow her own saliva. Ultimately, Ellen’s encased respiratory muscles were unable to generate the tidal volume of air sufficient to sustain her life, and she passed away.

Political Power Play in Washington

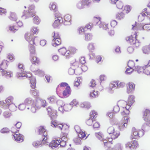

LT had been commercially available in the U.S. for 15 years until its recall by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in late 1989. An essential, naturally occurring amino acid that serves as a precursor for serotonin biosynthesis, it gained its widest use in the treatment of insomnia. The development of EMS was ultimately linked with the ingestion of a contaminated form of LT, derived solely from one of the primary manufacturers in Japan, which had recently altered a number of its manufacturing processes. Eosinophil activation and the release of a major basic protein and other eosinophil-derived toxic proteins into the extracellular space was a striking feature in EMS. In more severe cases, there was mononuclear cell activation and infiltration of various affected tissues as well as fibrosis of the integument and of the connective tissue components of blood vessels, nerves and muscles.3

This newly described disorder caught the attention of the FDA and its commissioner at the time, David Kessler, MD. Dealing with the repercussions of an alarming 38 deaths related to the contaminated stocks of LT, he grew increasingly wary of the growing number of unsubstantiated health claims made by some supplement manufacturers. Dr. Kessler instructed the agency to conduct raids and confiscate supplements deemed unsafe or sold for unapproved uses.4

A task force that was convened to review how supplements should be regulated concluded that health claims for dietary supplements should be made only when there is significant scientific agreement to support these assertions. This was a common-sense idea, but this recommendation threw the supplement industry into a state of panic because health claims were the prime driver of their products’ sales. Without the hype, there would be fewer buyers. A lawyer representing the manufacturers voiced their resistance to these changes: “ … the products will be taken off the market because they won’t take the health-claim labeling off. They are the lifeblood of the industry.”5