It’s disheartening to stand by and watch helplessly as your patient dies a slow, painful death. In spring 1990, I had the misfortune of living through such a distressing experience.

Strange happenings in New Mexico & Japan

Ellen was a bookkeeper in her late 40s, living quietly in suburban Boston. For years, she hid a dark secret from her family, her alcohol abuse. Every day, she would deal with the daily stresses of life by consuming copious quantities of liquor. After several failed efforts, she finally succeeded in quitting her drinking. Being sober felt great, but Ellen could not cope with the insomnia that her abstinence seemed to induce. She just could not sleep. A benzodiazepine prescribed by her doctor allowed her to sleep soundly again, but one day it dawned on her that she was becoming addicted to the drug.

Determined to kick this new habit, she began seeing a psychiatrist who recommended a “safe and natural remedy” for her to use as a sleep aid. It sure seemed to work. Each night, after taking one of these tan-colored pills, she would doze off quickly and awaken in the morning feeling refreshed. Best of all, this pill was just a supplement—totally safe and no prescription required.

Rheumatologists must ensure they ask about dietary supplements, not just medications, because patients often won’t think to volunteer that information.

Image Credit: Pressmaster/shutterstock.com

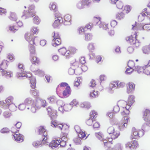

Ellen felt fine and her life returned to normal. Then, out of the blue, she began a slow descent into misery. First, she noticed an odd, eerie feeling; she felt stiff—very stiff actually, as though her entire body was becoming encased in concrete. She visited her primary care doctor, who was baffled. A rheumatologist raised the possibility of systemic sclerosis, but the absence of Raynaud’s phenomenon made this diagnosis suspect. Then came the pain. Ellen was plagued by debilitating myalgia and an unrelenting stabbing sensation in her extremities that a neurologist surmised was due to a rapidly developing polyneuropathy. The million-dollar workup she underwent yielded few helpful clues, except for an unexplained peripheral eosinophilia (see “Eosinophilia: A Practical Guide for the Rheumatologist,” p. 1). In fact, she seemed to be harboring eosinophils everywhere: her blood, her bone marrow and scattered throughout her cement-like soft tissues.

By the time Ellen appeared in our clinic, the cause of her illness had been unmasked. Several months earlier, in October 1989, the New Mexico Department of Health and Environment was notified of three previously healthy women who developed marked peripheral eosinophilia and incapacitating myalgia. All had been consuming oral preparations of the amino acid L-tryptophan (LT), Ellen’s miracle sleep aid.1

Even though these women had undergone extensive clinical evaluation and testing, their illnesses were inconsistent with any known condition that would typically be listed on the lengthy differential diagnosis of eosinophilia. An astute epidemiologist spotted a potential relationship to the notorious toxic oil syndrome that had devastated parts of Spain just a few years earlier.2

At the time of Ellen’s diagnosis of eosinophilia myalgia syndrome (EMS), approximately 1,000 cases had been reported. Although the vast majority of patients experienced an improvement or at least a stabilization of their symptoms following cessation of their use of LT, Ellen was one of the unlucky few whose illness spiraled into a slow death march. Her symptoms over the final months of her life resembled those observed in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. She could no longer move, feed herself or even swallow her own saliva. Ultimately, Ellen’s encased respiratory muscles were unable to generate the tidal volume of air sufficient to sustain her life, and she passed away.

Political Power Play in Washington

LT had been commercially available in the U.S. for 15 years until its recall by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in late 1989. An essential, naturally occurring amino acid that serves as a precursor for serotonin biosynthesis, it gained its widest use in the treatment of insomnia. The development of EMS was ultimately linked with the ingestion of a contaminated form of LT, derived solely from one of the primary manufacturers in Japan, which had recently altered a number of its manufacturing processes. Eosinophil activation and the release of a major basic protein and other eosinophil-derived toxic proteins into the extracellular space was a striking feature in EMS. In more severe cases, there was mononuclear cell activation and infiltration of various affected tissues as well as fibrosis of the integument and of the connective tissue components of blood vessels, nerves and muscles.3

This newly described disorder caught the attention of the FDA and its commissioner at the time, David Kessler, MD. Dealing with the repercussions of an alarming 38 deaths related to the contaminated stocks of LT, he grew increasingly wary of the growing number of unsubstantiated health claims made by some supplement manufacturers. Dr. Kessler instructed the agency to conduct raids and confiscate supplements deemed unsafe or sold for unapproved uses.4

A task force that was convened to review how supplements should be regulated concluded that health claims for dietary supplements should be made only when there is significant scientific agreement to support these assertions. This was a common-sense idea, but this recommendation threw the supplement industry into a state of panic because health claims were the prime driver of their products’ sales. Without the hype, there would be fewer buyers. A lawyer representing the manufacturers voiced their resistance to these changes: “ … the products will be taken off the market because they won’t take the health-claim labeling off. They are the lifeblood of the industry.”5

In the end, the industry had nothing to fear. The methodical and rational safety recommendations of the FDA that threatened to upend their business model were no match for the often irrational and always politically attuned U.S. Congress. When dealing with issues affecting the pocketbooks of their donors, politicians can expediently turn fiction into fact or vice versa. The FDA task force recommendations were quietly shelved, and in their place in 1994, Congress enacted the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which allowed the marketing and sale of dietary supplements with little or no regulation by the FDA.2 Manufacturers were merely advised to provide “truthful” product label information and to police themselves. As long as product labels did not make claims about treating diseases but focused instead on promoting “organ health,” manufacturers would be in the clear. Hence, the proliferation of terms such as, “improving bone and joint health or boosting immune function”—thinly veiled references to such conditions as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus.

Congress granted literary license to manufacturers to embellish the efficacy of their products and placed it all beyond the reproach of the FDA. Just to be sure, most supplements include this nifty warning label describing their claims: “These statements have not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.”

Why would a revered institution that has produced outstanding physicians … & many of the current leaders of American medicine continue to allow its good name—its brand—to be tarnished by its association with Dr. Oz?

Does the self-policing of the industry demanded by Congress really work? No. Take the case of the supplement, ephedra, which had been well studied and described as a health hazard causing serious toxicities, including cardiac arrest (New England Journal of Medicine) in 2000.6 But it remained on the market for another three years. Ephedra was found to have contributed to the death of pitcher Steve Bechler of the Baltimore Orioles, who died suddenly during spring training, and the subsequent intense media glare finally led to the supplement being banned 10 months following his death. By then, ephedra was linked to 155 deaths and more than 16,000 serious adverse events.

The lack of regulatory oversight can lead to other problems. According to an FDA estimate, 70% of supplement makers fail to adhere to practices designed to prevent adulteration.

Earlier this year, New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman investigated herbal supplements sold by four major retailers. Using an advanced DNA testing procedure, investigators found that four out of five bottles contained no detectable genetic material from the plants advertised on their labels.7 Some contained filler, such as powdered rice, wheat and bits of houseplants. Others tested positive for potentially toxic ingredients including amphetamines, fluoxetine, anabolic steroids and sildenafil. Not surprisingly, just over the past two years, there have been 33 fatalities, and nearly 2,300 serious illnesses associated with the use of dietary supplements. A recent study found that about two-thirds of dietary supplements recalled by the FDA still contained banned substances at least six months after being recalled.8

So much for self-policing.

Oz, the Wizard

With all the negative media surrounding dietary supplements, one might expect the public’s appetite for these products to be diminished. In fact, the $33 billion supplement industry continues to flourish, aided and abetted by a wide cast of supporters, ranging from lobbyists in Washington, led by the son of the author of the DSHEA and five of this senator’s former aides, to its vocal, celebrity boosters who pump up the sales of these products. Some, such as Kevin Trudeau, have a checkered past, including felony convictions and multimillion-dollar fines. Others, including Joe Mercola, DO, an osteopathic doctor in Illinois, promote outrageous claims that have repeatedly run afoul of even the hamstrung FDA. But there is one individual whose influence far exceeds the sway of these mere mortals—Mehmet Oz, MD.

Dr. Oz, once hailed for his talents as a skilled cardiovascular surgeon, rose to the rank of vice chair of surgery at Columbia University in New York City. After a series of frequent appearances with Oprah Winfrey, he was given his own television show, which became enormously popular, attracting at its peak in 2011, nearly 4 million viewers per week. Dubbed, “America’s Doctor” by Ms. Winfrey, he has repeatedly espoused his beliefs that miracle cures can be found in many of the products that he promotes. For example, Dr. Oz promoted garcinia cambogia, African mango seed and, in particular, green-coffee bean extract as weight-loss marvels, even though all lack data to support their health claims.

“You may think that magic is make believe,” Dr. Oz said at the beginning of one typical show, “but this little bean has scientists saying they have found a magic weight-loss cure for every body type. It’s green coffee beans, and, when turned into a supplement, this miracle pill can burn fat fast. This is very exciting. And it’s breaking news.”9

Following the broadcast of this show, several companies sold tens of millions of dollars’ worth of the supplement. This phenomenon has become known as the “Oz effect.” The Federal Trade Commission (unlike the FDA, it is not legally barred from taking action) subsequently sued the companies for false and deceptive advertising. In January, the man behind two of the companies agreed to refund $9 million to customers.10

Recently, Dr. Oz has come under attack from a group of physicians who have raised questions about his various questionable endorsements and his disdain for evidence-based medicine. How does Dr. Oz get away with his shtick? Despite his outlandish claims, he is a talented and telegenic showman who intersperses some useful medical advice concerning previously taboo topics on medical shows, such as menopause and bowel movements. After all, why wouldn’t a viewer trust a doctor who carries the imprimatur of Columbia University? There are constant reminders of his status as an important doctor at a very important medical institution, including video segments depicting him hard at work in the operating room or holding the hand of a sick patient at their bedside. Lest the viewer forget, he often dons his favored studio outfit, surgical scrubs. This is what is most baffling about the show: Why would a revered institution that has produced outstanding physicians, countless Nobel laureates (including physicians Edward Kendall, Joshua Lederberg, Baruj Benacerraf and Harold Varmus, to name a few) and many of the current leaders of American medicine continue to allow its good name—its brand—to be tarnished by its association with Dr. Oz?

As the columnist Frank Bruni recently opined in, The New York Times, there has been an unsettling corruption of academia by celebrity culture. Whether it is Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates self-censoring his television show at the request of the actor Ben Affleck or the University of Houston spending $155,000 to schedule actor Matthew McConaughey to give its commencement address this spring, some academic institutions are blurring the lines between academic virtues and celebrity values.11

This does not bode well for any of us. To quote Thomas Paine, “Character is much easier kept than recovered.”

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Eosinophilia-Myalgia Syndrome—New Mexico. MMWR. 1989 Nov 17;38(45):765–767.

- Kilbourne EM, Riagu-Perez JG, Heath CW Jr., et al. Clinical epidemiology of toxic-oil syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983 Dec 8;309(23):1408–1414.

- Varga J, Uitto J, Jimenez SA. The cause and pathogenesis of the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Jan 15;116(2):140–147.

- Lipton E. Support is mutual for senator and Utah industry. The New York Times. 2011 Jun 20.

- Burros M. FDA is again proposing to regulate vitamins and supplements. The New York Times. 1993 Jun 15.

- Haller CA, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000:343;25:1833–1838.

- O’Connor A. GNC to strengthen supplement quality controls. The New York Times. 2015 March 30.

- Cohen PA, Maller G, DeSouza R, et al. Presence of banned drugs in dietary supplements following FDA Recalls. JAMA. 2014 Oct 22–29;312(16):1691–1693.

- Specter M. Columbia and the problem of Dr. Oz. The New Yorker. 2015 Apr 23.

- Federal Trade Commission. Marketer who promoted a green coffee bean weight-loss supplement agrees to settle FTC charges. 2015 Jan 26.

- Bruni F. Hollywood trumps Harvard. The New York Times. 2015 April 22. http://nyti.ms/1yQYQvB.