It has been about 20 years since the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published the report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, shining light on the impact of medical errors in healthcare.1 In response to that publication, the focus on quality improvement (QI) started in the inpatient setting, where the need was most acute and evident. Learning how to improve the quality of outpatient care, with its long timelines and multiple points of contact, is more challenging, and has developed and been implemented more slowly.

It has been about 20 years since the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published the report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, shining light on the impact of medical errors in healthcare.1 In response to that publication, the focus on quality improvement (QI) started in the inpatient setting, where the need was most acute and evident. Learning how to improve the quality of outpatient care, with its long timelines and multiple points of contact, is more challenging, and has developed and been implemented more slowly.

During the same 20 years, we have witnessed an evolution in graduate medical education. In 1999 our educational efforts began to incorporate core competencies for medical education.2 Previous efforts were focused on what we now call medical knowledge and patient care competencies, but expectations have evolved to include additional competencies to prepare trainees to care for their patients, develop careers as lifelong learners and care for themselves.

Accreditation expectations have evolved in parallel. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) previously focused on process-based requirements for training programs, but in the new accreditation system, oversight is directed more toward learning outcomes and ensuring trainees experience broad-based development of many skill areas necessary for becoming competent practitioners.3 To that end, ACGME program requirements for rheumatology include QI education to maintain accreditation (see Table 1).

Table 1: ACGME Rheumatology Requirements Pertaining to Quality Improvement

| VI.A.1. Patient Safety and Quality Improvement All physicians share responsibility for promoting patient safety and enhancing quality of patient care. Graduate medical education must prepare fellows to provide the highest level of clinical care with continuous focus on the safety, individual needs, and humanity of their patients. It is the right of each patient to be cared for by fellows who are appropriately supervised; possess the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities; understand the limits of their knowledge and experience; and seek assistance as required to provide optimal patient care. Fellows must demonstrate the ability to analyze the care they provide, understand their roles within health care teams, and play an active role in system improvement processes. Graduating fellows will apply these skills to critique their future unsupervised practice and effect quality improvement measures. |

| VI.A.1.b).(1).(a) Fellows must receive training and experience in quality improvement processes, including an understanding of health care disparities. (Core) |

| VI.A.1.b).(3).(a) Fellows must have the opportunity to participate in interprofessional quality improvement activities. (Core) |

With the advent of pay for performance and other national initiatives to link reimbursement to patient outcomes, programs to ensure trainees are prepared for the current and future practice environment require an in-depth understanding of the science and methodology of QI.

Why Devote Time to a QI Curriculum?

Rheumatology trainees have to master a daunting amount of knowledge and skills during a two- or three-year training program, so how can we justify devoting significant time and effort to teaching QI?

- As physicians, we should always strive to improve the quality of care we deliver. Medical knowledge is changing every day. It is well known that it takes many years for medical evidence to make its way into routine clinical practice. We should want to do better, training our future partners to practice smarter and in a more evidence-based fashion to improve the health of the communities we serve.4

- QI is a crucial skill for physicians’ future careers; therefore, it is imperative that training programs include a focus on this skill. Teaching QI and guiding trainees to reflect on healthcare delivery systems will never be obsolete. QI is a durable skill fellows will be able to use throughout their careers.

- Fellows have incomplete QI experience from medical school and residency, during which time they tend to rotate through QI projects, working only on a small portion of the QI process. Without the experience of seeing a project through from conception to completion, new residency graduates are often unprepared to lead QI projects. Rheumatology fellowship, with a small group of fellows who work closely together, is a great time to round out their QI education and experience.

- Participating in a QI project gets fellows engaged in the institution’s clinical practice. This involvement is empowering for fellows who are given a stake in the success of the training program’s practice. Through the development of, and participation in, a QI project, fellows feel like a part of the practice, with the power to make change, and can envision measures to improve their own practice.

- Working together on a QI project is good for team building. Current fellows participate in team-based learning throughout medical training, so are used to working in groups. However, becoming part of an outpatient practice team that includes a consistent cast of attending physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists and other clinical staff is a new experience for many fellows, and working together with an interprofessional group to achieve the shared goal of improved patient care helps build high-functioning teams and develops the skills needed to work in such environments moving forward.

A Longitudinal, Experiential QI Curriculum

When we decided to start a QI curriculum in early 2013 to meet ACGME RRC (Residency Review Committee) requirements, our program had never completed a clinical QI project, and no one on our rheumatology faculty had appropriate knowledge or experience to teach QI. Fortuitously, in 2013, the rheumatology program director (note: Lisa Criscione-Schreiber) was mentoring a recent geriatrics fellowship graduate who had developed a clinical QI curriculum she was eager to implement and evaluate.

This initial curriculum was a five-session, four-month-long course. Objectives were that, by the end of the course, rheumatology fellows would be able to: 1) develop a QI project proposal; 2) implement a QI project; and 3) collect and analyze data for said project during a plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle. Each session included a 20-minute didactic presentation, an hour-long participatory exercise and homework to be completed by the next session. Fellows divided into three groups, each of which worked through the process of developing and implementing a QI project (see Table 2).

Table 2: Structure of the Initial 5-Session QI Curriculum10

| Session | Didactic | Group Exercise | Homework |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to the process of quality improvement | Form 3 groups and identify group leaders | Selected readings from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement text book11 |

| 2 | How to write an aim statement, identifying stakeholders and defining the local problem | Groups choose an area to improve and write aim statements | Textbook readings Literature search on chosen topic Groups write background page and define the local problem |

| 3 | The process model and QI measures | Groups work through aspects of their QI | Textbook readings Write an Institutional Review Board QI proposal |

| 4 | Teamwork and the model for improvement | Plan PDSA cycle 1 | Textbook readings Carry out PDSA cycle 1 |

| 5 | Making changes to a system | Together analyze data from groups’ PDSA cycle 1 Based on results, plan the next PDSA cycle intervention | Complete QIKAT |

The five sessions were followed by completion of the QIKAT, a validated QI education measurement to determine what the group had learned.5 This curriculum provided a solid introduction to the science of quality improvement and the opportunity to see a project from conception through completion of a single PDSA cycle. Thus, it served an educational need and is a model that can be implemented by other programs.

Looking to expand on the success of the five-session QI curriculum, in 2014, we established a programmatic objective that “by the end of training, every Duke rheumatology program graduate will have sufficient education and experience to lead QI efforts in their future practice.” Meeting this goal required evolving the course project.

In 2014, we decided all fellows would focus on a single, group project; they decided to focus on contraception counseling for women taking teratogenic medications. We had one QI curriculum session monthly, and still used the five-session curriculum of didactics, group work and homework to teach QI methodology. We added four monthly sessions to conduct and analyze additional PDSA cycles.

The 2016 project on documentation of disease-activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis … led to a 38% increase in provider-documented use of RAPID3 scores in decision making.

In 2015, the curriculum was led by another faculty member who simultaneously completed the Teaching for Quality program through the Association of American Medical Colleges.6

That year the fellows chose to incorporate RAPID3 (routine assessment of patient index data 3) into our clinic, an effort that resulted in 93% RAPID3 completion clinicwide, a goal that has been sustained over several years.

In 2016, the program director taught the monthly course again, designating one fellow as the project leader based on her ongoing enrollment in the Duke graduate medical education concentration in patient safety and quality improvement and serving as the training program’s representative to the Duke Patient Safety Council. The fellows chose to focus on treat to target and barriers to achieving remission using RAPID3 as a measure.

In 2017, we evolved the fellow-as-project-leader concept even further, and one of the second-year fellows (note: Ryan Jessee, now a faculty member) with an interest in QI was invited to not only lead the project, but teach the didactic curriculum with the program director’s supervision and guidance. The fellow project that year focused on implementing hydroxychloroquine dosing guidelines.

QI sessions were scheduled monthly starting in July to allow more time for data collection. With monthly meetings, we expanded the content of didactic sessions to include creating and submitting an institutional review board protocol and creating a REDCap database (a secure web application for building and managing surveys). Once PDSA cycles were underway, didactic sessions included such topics as patient safety, morbidity and mortality review, and SQUIRE (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence) guidelines for QI reporting.7 We also included in-person collaborative data analysis and dedicated sessions to co-write the abstract for submission to the ACR/ARP Annual Meeting.

Additionally, fellows present their QI project several times each year in Rheumatology Grand Rounds to gain divisional buy-in and keep members abreast of project progression. We incorporated time at the end of each QI session to discuss potential improvements to the fellowship program in general, capitalizing on a time when fellows felt empowered to drive change.

Curriculum Evaluation & Results

This curriculum has successfully produced positive outcomes. Several fellows have developed expertise in QI, with one fellow each year from 2014–17 completing the Duke Patient Safety and Quality Improvement GME Concentration program (the certificate program ended after 2017). Subsequent fellows from 2017, 2018 and 2019 have completed the Duke Learning Health Systems Training Program.

The curriculum has given every fellow an opportunity to complete a project that includes scientific writing and presentations. Every year since 2015, our fellows’ project abstracts have been accepted for presentation at the ACR/ARP Annual Meeting; one project was published as a full manuscript (see sidebar, left).8

In informal graduate surveys, at least three former fellows are leading QI projects in their current practice. A 2016 graduate served on the ACR’s Quality Measures Subcommittee to the Committee on Quality Care and implemented the RISE (Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness) registry in her practice.

Physician fellows are not the only ones who have benefited from this participatory curriculum: In 2016, a medical assistant who participated in the curriculum presented her own clinical QI project at a national ACR nursing meeting. One of Duke’s nurse practitioners who participated in the QI curriculum during her training completed a clinical QI project using team-based methods to ensure rheumatology clinics adhered to North Carolina law for prescribing and monitoring opioid analgesic prescriptions; she has subsequently obtained institutional grant funding for this project, which she is implementing across the Duke Health system.9

Current State & Future Plans

The QI curriculum continues to evolve to meet the educational needs of our fellows and the clinical needs of rheumatology practice. In 2018, a second-year fellow (note: David Leverenz, now a faculty member) led the curriculum and project while concurrently enrolled in the Duke Learning Health Systems Training Program (LHSTP), which trains residents and fellows in data science methodologies that can be used to analyze health system data for clinical care, QI and research. This inspired the exploration of data streams that could be used to address one of the biggest limitations of the QI curriculum to date: the need for extensive manual chart review.

Manual chart review is universally disliked; it is tedious, time consuming and detracts from the educational value of the QI curriculum. In addition, reliance on manual chart review prevents sustainable analysis of practice patterns after each QI project concludes. For example, the 2016 project on documentation of disease-activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis required brief review of more than 3,000 patient encounters to identify more than 600 rheumatoid arthritis patient charts for detailed review. This important work led to a 38% increase in provider-documented use of RAPID3 scores in decision making; however, the only way to assess if this work led to sustainable change would be to re-do the manual chart review.

In our health system, multiple electronic health record (EHR) based tools are already available to track provider and patient data. None of these tools are perfect, and some manual data analysis will likely always be necessary for data validation. However, we have already started to realize some benefits from transitioning to these sources of data.

In 2018–19, the fellows performed a QI project focused on improving documentation efficiency. Data were collected using an EHR tool called Signal that automatically tracked metrics on provider activity within the EHR, such as documentation time and the percentage of notes composed using manual entry, dictation, smart tools and copy/paste. By using these data, fellows were able to focus on learning the principles of QI and designing PDSA cycles to improve documentation efficiency, rather than spending most of their time collecting the data.

Further, the constant stream of data allowed us to actually perform the “S” (study) part of the PDSA methodology, studying the impact of our changes in real time and using those data to inform subsequent interventions.

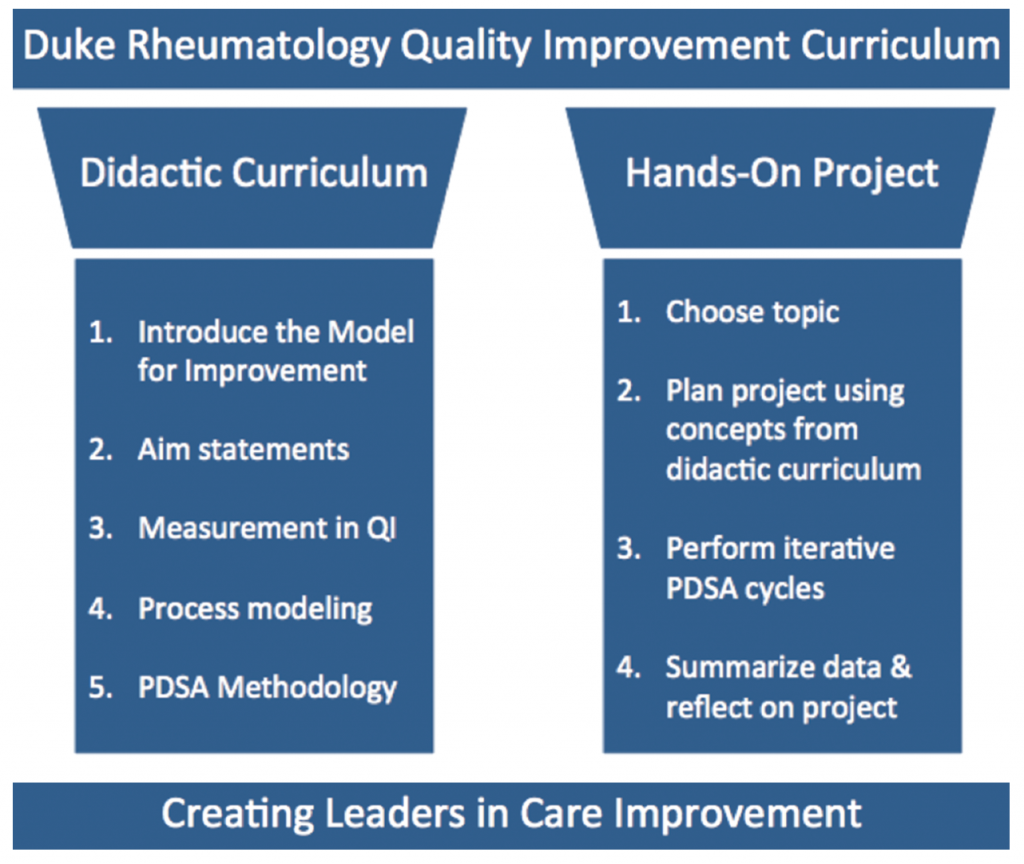

Figure 1: 2 Pillars of Success for the Duke Rheumatology Quality Improvement Curriculum

Moving forward, the objective of our QI curriculum continues to be developing rheumatologists with sufficient knowledge and experience to lead QI efforts in their future practice. This goal is balanced, but not eclipsed, by the desire to use the quality curriculum to make real improvements in our clinical practice.

Our curriculum remains based in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement, and we continue to provide a didactic series on that methodology, combined with real-world application in a yearly, fellow-led QI project (see Figure 1).

As modern medicine inches closer to the realities of value-based care, our fellows are being trained in the use of data science and learning health principles to analyze practice patterns in sustainable ways.

One doesn’t have to look far to see the value of this type of training. The RISE registry is gaining momentum, the ACR continues to develop quality measures for rheumatology practice, and legislators continue to debate the implementation of various quality incentive programs. Meanwhile, patients continue to suffer from medical errors, outdated practices, system inefficiencies, treatment delays, insufficient care and overtreatment. Upon graduation, our fellows will be ready to engage these issues and lead quality improvement initiatives for the betterment of patient care.

Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, MEd, is an associate professor of medicine, rheumatology program director and vice chair for education, Department of Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C. Her academic interests include medical education, mentoring and SLE.

Ryan Jessee, MD, is a clinical associate at Duke University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology and Immunology. His interests include musculoskeletal ultrasound and advocacy.

David Leverenz, MD (@DavidLeverenz), is an assistant professor of medicine and rheumatology associate program director at Duke University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology and Immunology. His academic interests include medical education and quality improvement.

Project Abstracts Accepted for ACR/ARP Presentation

- 2015 (abstract 2505): Wells M, Lackey V, Peart E, et al. A fellow led quality improvement project for improving contraceptive compliance for women receiving teratogenic medications.

- 2015 (abstract 2513): Sadun R, Holdgate N, Wells M, et al. Contraception use amongst women ages 18–45 taking known teratogenic medications in an academic rheumatology clinic.

- 2016 (abstract 1416): Wells M, Sadun R, Jayasundara M, et al. Sustained improvement in documentation of disease activity measurement as a quality improvement project at an academic rheumatology clinic.

- 2017 (oral presentation; 1797): Jayasundara M, Jessee R, Weiner J, et al. Insights from treating to target in rheumatoid arthritis at an academic medical center.

- 2018 (abstract 1243): Jessee R, Giattino S, Kapila A, et al. A quality improvement initiative to increase adherence to hydroxychloroquine dosing guidelines at an academic medical center.

- 2019 (abstract 1190): Leverenz D, Golenbiewski J, Andonian B, et al. A quality improvement project to increase documentation efficiency in an academic rheumatology practice.

References

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Swing SR, Clyman SG, Holmboe ES, Williams RG. Advancing resident assessment in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2009 Dec;1(2):278–286.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 15;366(11):1051–1056.

- Guise J-M, Savitz LA, Friedman CP. Mind the gap: Putting evidence into practice in the era of learning health systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Dec;33(12):2237–2239.

- Singh MK, et al. The quality improvement knowledge application tool revised (QIKAT-R). Acad Med. 2014 Oct;89(10):1386–1391.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Teaching for quality: Program overview.

- Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. Am J Crit Care. 2015 Nov;24(6):466–473.

- Sadun RE, Wells MA, Balevic SJ, et al. Increasing contraception use among women receiving teratogenic medications in a rheumatology clinic. BMJ Open Qual. 2018 Jul 25:7(3):e000269.

- Carnago L, Hall J, Puryear S. How to improve opioid prescribing in an outpatient clinic. The Rheumatologist. 2019 Oct;(13(10):38–40.

- Yanamadala M, Criscione-Schreiber LG, Hawley J, et al. Clinical quality improvement curriculum for faculty in an academic medical center. Am J Med Qual. 2016 Mar–Apr;31(2):125–132.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI Open School. 2020 Mar.