In his critically acclaimed book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman lays out his theories about how we analyze and interpret data. Kahneman divides the thought process into two systems.1 System 1, or thinking fast, uses association and metaphor to generate a rapid analysis of the issue at hand. It functions quickly without deliberation, and does not require much oversight. Think autonomic nervous system. In contrast, System 2, responsible for thinking slowly, provides the more thoughtful, careful and reasoned analysis. It is probing and questions our assumptions about issues. System 2 represents the epitome of higher cortical brain function.

In one of Kahneman’s classic experiments assessing how one might enhance the activation of System 2, a group of Harvard undergraduate students were asked to solve a simple puzzle about the likely occupation of a hypothetical graduate student. They were provided with a set of variables including his possible fields of study and a personality sketch. “Half of the students were told to puff out their cheeks during the task, while the others were told to frown. It turns out that frowning generally increases the vigilance of System 2 and reduces both overconfidence and the reliance on intuition.” So, I am asking all readers to frown for the next several minutes as you read about some novel and interesting research findings. Intuitively, these studies may seem far afield from rheumatology. The first concerns the relationship between microbes and their hosts. The second describes the role for Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) as a vaccine that could attenuate type I diabetes. The third attempts to explain how an emotional stress such as depression can increase the risk of developing bone metastases in women with breast cancer. To paraphrase the late Steve Jobs, we need to be creative and “think different.”

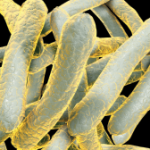

The Gut of the Matter

This past summer, it would have been very difficult to avoid reading something about how microbial flora impacts our health. The human microbiome, a term coined by the late Joshua Lederberg, MD, consists of all microbes, their genomic material, and the sum total of their interactions within the host, namely each and every one of us. There are 10 times more microbial cells than human cells in the body. In total, the microbiome harbors 3,000 kinds of bacteria with 3 million distinct genes, compared with just 18,000 genes belonging to our own cells. In an excellent review of the topic, published in The Rheumatologist, Jose U. Scher, MD, clinical instructor of medicine, and Steven B. Abramson, MD, professor of medicine, both at the New York University School of Medicine, describe how the gut microbiota should be viewed as an extension of the self.2 As the authors stress, its rich milieu contains far more genetic and antigenic material than the host. They lay out in elegant detail how the microbiome may drive the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the spondylarthropathies.