Let’s start with a couple of short riddles:

- What question can you never answer “yes” to?

- Which word does not belong in the following list: stop cop mop chop prop or crop?

[The answers appear at the end of this article.]

Riddles are designed to make us think beyond the obvious answer. There is usually no immediately accessible response, so they force us to consider how we are being misled and design a mental strategy to get to the correct response. The way we approach riddles is similar to the way we approach other mental challenges.

2 Modes of Thinking

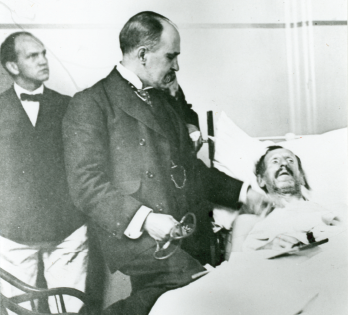

FIGURE 1: William Osler, the distinguished early 20th century physician at the bedside. What resources did Osler have in his System 2 thinking to make diagnostic and therapeutic decisions a century ago compared to what we have now? Whose System 2 is more stressed? “What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived we dream.”11

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, the economist and psychologist Daniel Kahneman, PhD, defines two types of thought, which he calls System 1 and System 2.1 System 1 is our fast-thinking brain. We live the vast majority of our life in System 1, which allows us to swiftly respond to threats and most routine situations. Our distant forebears had to make important decisions that could determine if they lived and got to pass on their genes. For these early humans, survival favored the assumption of danger and loss. Thinking slowly could kill you.

Long ago, if a person heard rustling in the bushes he might conclude, based on past experience, that the rustling was just the wind. Although the assumption might be correct the majority of the time, if the rustling turned out to be a saber-toothed tiger even once, the cost of this false negative (a type 2 statistical error) is not good. If, instead, he assumed a tiger was in the underbrush and climbed the nearest tree every time he heard a rustling sound, but it turned out to be the wind—avoiding a loss or a false positive or type 1 statistical error—he lived to pass on his genes.

Human beings were unlikely to survive many false negative errors and still become ancestors of present-day humans. Thus, evolutionary psychology and survival has been dependent on a loss counting more than a gain. To demonstrate this central human behavior, Dr. Kahneman gives many examples in which rational human beings make decisions to avoid a perceived loss, even when the loss value is less than the potential upside. He published his findings in a paper on decision theory and received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002.2

There is more. Dr. Kahneman states that System 1 immediately engages our memory of recent events and context—your lived experience or availability heuristic—to provide us with a solution to a problem. Unfortunately, System 1 only remembers the winning brain interpretations and not any alternative considerations, so our immediate memory is not complete. In Dr. Kahneman’s words, “conscious doubt is not in the repertoire of System 1” because the implications of doubt require both mental energy and time. Both of those qualities are the domain of System 2. It is the system you used to try to solve the riddles.

Dr. Kahneman uses words like lazy and indolent to describe System 2. We use System 2 when solutions to problems are not immediately available. He calls System 1 gullible and biased to believe, whereas System 2 is in charge of doubting and unbelieving. He uses the acronym WYSIATI (what you see is all there is) to describe System 1’s superficial reasoning.

When I read the piece by Philip Seo, MD, in the September 2021 issue of The Rheumatologist, it became apparent to me that the conspiracy believers described were not engaging System 2.3

But Dr. Kahneman also makes it clear that System 2 is not foolproof. It is dependent on experience, education and open-mindedness, as well as what he calls general mental ability, or GMA. System 2 can be used to substantiate and buttress a System 1 conclusion. Dr. Kahneman indicates that System 2 can be susceptible to the biasing influence of so-called anchors, which make information easier to retrieve. Although anchors help streamline brain function, System 2 doesn’t consciously control what information becomes an anchor and is unaware when an anchor has influenced its judgment. And the less we know to inform a judgment, the more that judgment is susceptible to the anchoring effects of personal bias.

To illustrate the anchoring effect, Dr. Kahneman gives an example of experienced real estate agents asked to provide an ideal selling price for a house they inspect. Teams provided with an unrealistically high suggested value (the anchor) will subsequently agree on a price that is substantially higher than an equally savvy group provided with a much lower suggested valuation. Vaccine unbelievers may similarly think that unproven remedies can successfully treat COVID-19 if they repeatedly hear from an anchor source they trust that they are useful. If System 1 hears vaccines are dangerous and a particular agent is curative, it does not examine if the anchor could be faulty. And System 2 is not foolproof.

The mental effort required to operate in System 2 can actually be witnessed. To demonstrate this point, Dr. Kahneman asks the readers of Thinking, Fast and Slow to do a sequential addition problem while simultaneously maintaining a specified rhythm on a drum. If you were to film your eyes while performing the exercise, you’d see your pupils dilate with the effort.

Consider a day in the clinic. Let’s say you see 20 patients from start to finish. How often do you believe you engage System 2? After years in practice, solutions to routine problems typically reside in System 1. But experienced physicians will still have the occasional challenging problem.

Now, consider a day in which four patients present with a complex medical issue not within the readily accessible context of our experience. Four out of 20 patients would constitute a very challenging day. But what if it were 10 of 20? That day would be impossibly draining and difficult to bear. We would be engaging System 2 throughout the day, while also satisfying the documentation demands of the electronic medical record (see Figure 1); it would be like adding the numbers while maintaining the drum rhythm. You would leave the office feeling fried and depleted. After a day like this it would be hard to remember something as simple as the drive home.

How Bias & Noise Impact Judgment

Many other factors influence how we humans make decisions. In the recent book Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, Kahneman et al. outline many challenges to our rationality, including bias and noise.4 Noise refers to the natural propensity for different people’s judgments and decisions to vary even when presented with identical situations. Although we recognize these variations in other fields, we often don’t acknowledge that noise impacts both our personal and collective judgments. We are less consistent personally, and collectively, than we like to believe.

Picture yourself as a member of a diagnostic group reviewing a challenging medical case. There may be a variety of judgments in the room, but there can only be one correct answer. The collective decision can miss the mark. The variations from the correct response are statistical noise.

Much has been written about the potential influence of bias in peer review. To try to eliminate bias, reviewers of submissions to medical journals are asked to declare any conflicts up front. Does this requirement eliminate judgment bias if most of us are unaware of, or possibly unable to acknowledge, our biases? The answer to that question depends on whether or not the reviewers have processed their judgments through System 2, or if they have used familiar mental heuristics to reinforce bias found in System 1.

In Noise, we learn about the many different forms of bias that are routinely encountered. One is the bias of the order of opinions in a group. A strongly expressed opinion from an influential and respected individual can demonstrably affect the presumably independent judgments of others in the room (i.e., the anchoring effect) (see Figure 2), especially if that person is the first to speak.

FIGURE 2: A groups trying to make a collective judgement aware of the biases they bring to the table and the resultant noise around the ideal decision? What anchoring effects can skew the process? (credit GoodStudio/shutterstock.com)

A halo effect describes a judgment based upon a first impression that can be as superficial as a handshake. This first impression is a prejudgment that causes us to ignore subsequent conflicting evidence that might undermine our original judgment. If my trusted television personality reports that something is true, then it must be correct.

Fascinating examples of situational bias (i.e., occasion bias) are well documented. Judges presented with the same case and circumstances will render different sentences at different times. Fingerprint experts will offer different judgments on the same prints on different days. Parole boards are more likely to deny parole later in the day. Physicians are more likely to prescribe opioids later in the day.5

Besides mental fatigue associated with time of day, other vagaries that affect judgment are mood, weather and the recent receipt of emotional news. Humans render more lenient judgments in the setting of a recent positive event, including news on a favorable outcome for a family member or notification of a positive personal outcome unrelated to the judgment.

Kahneman et al. do provide us with strategies to diminish both bias and noise using a process they call decision hygiene.4 The authors provide several steps to achieve good decision hygiene that are beyond the scope of this piece. Perhaps the most important is that “a judgment is not the place to express your individuality.”

Nudges

Nudges can move people in the right direction when making a judgment.6 Judgments are, of course, ubiquitous in medicine. The system for developing treatment guidelines can avoid many of the pitfalls associated with bias and noise. However, this process is labor intensive. Many different publications must be reviewed before guidelines can even be established. Then, a group of (presumed) experts must consider the evidence and try to recommend the best pathways or judgments that have been derived from the medical literature.7 This is clearly deep System 2 stuff.

However, real-life treatment decisions may not change significantly after clinical guidelines are published.8 To get through the clinic day, practitioners are primarily using System 1. In addition, the loss (i.e., sacrifice of opportunities for more pleasurable activities) of actually reading and digesting the published guidelines may outweigh any perceived gain. System 1 will remain pleased with the current state of affairs, so that can be kicked down the road without regret.

What if research-proven pathways, or guidelines, can be routinely provided as new medical challenges arise? Using artificial intelligence, an electronic record system can provide prompts, or nudges, that are relevant to a problem. Imagine you have a patient with epistaxis, pulmonary infiltrates and hematuria. Nudges from a sophisticated database can provide the relevant literature on diagnostic probabilities and best treatment options. If you have a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who has failed conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and a tumor necrosis factor agent, nudges can inform your judgment regarding an array of treatment options.

With that said, it’s easy to see how frequent nudges may also be viewed as annoying or downright intrusive. Our default psychological position will quickly evolve to ignore the prompts if they are seen as time consuming or, worse, thought to undermine the value of physician judgment. Their presence may even imply that the individual dealing with the problem is unable to make the correct decision when left to their own devices. There can, thus, be an implicit loss of professional status or agency associated with both well planned nudges and carefully constructed guidelines. Much has been written about provider burnout. It’s easy to imagine how ubiquitous prompts could undermine the psychological need of the provider to think of themself as the most important decision maker in the room.

Avoid the Judgment Lottery

How does a patient, potential parolee, criminal at sentencing or private citizen following the news avoid what could be called a judgment lottery? Depending on the cable news channel we watch or the newspapers we read, truth has a very different ring. Was the election of 2020 stolen? Is climate change linked to human activity? Are immigrants a bad or good thing? Is a strong, charismatic leader always the best person for society’s ills?

Anchoring bias and the halo effect are associated with strong personalities. Kahneman et al. have documented that these associations can often lead to bad decisions with disastrous outcomes.4 Sound decisions may be made by apparently rational people in one domain even though other domains of their life are seemingly driven by faulty heuristics. How do we explain the earnest adherents to individuals like Jim Jones, Adolf Hitler, Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong?

To reframe this question according to decision theory: Do we have more to gain or to lose by following these people? Kahneman would say it depends on the perceived loss: how disrespected and without agency a person or group feels. Which option represents the greater loss? A person whose hair is on fire will jump into a cesspool to extinguish the flames. A hopeless individual, or society, may believe a mesmerizing liar who promises great things. WYSIATI: what you see is all there is. People will grasp at the possibility of a better option if their present circumstances, or station in society, has caused them to experience tangible suffering and/or disrespect.

The system for developing treatment guidelines can avoid many of the pitfalls associated with bias & noise.

The people making judgments on these important issues should not be thought of as either bad or good. They are just human. And humans are subject to all kinds of judgment biases based upon the convenient workings of System 1 and the complexity of System 2. We will passionately avoid loss, such as damage to our personal status, especially if the loss is also viewed as an assault on our tribal group, which anchors and validates our sense of self-worth. Vaccinations are bad. I know this based on the internet connections I inhabit (and that inhabit me) on a daily basis.

But there may be a way to help. As the esteemed author James Atlas wrote in his New York Times op-ed, “We can train ourselves to change if we work on it hard enough.”9 Self-awareness sets us free. Atlas notes that as we learn to change our own minds, “strangers can learn to be friends.”

As the brilliant philosopher and psychologist William James wrote, “The great thing then, in all education, is to make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy.”10

It starts with the individual with insight into their own biases and spreads to the group and then to society as a whole. An epidemic of open-mindedness is derived from an understanding of the manner in which we make important judgments and decisions.

In the words of the Beach Boys:

Maybe if we think and wish and hope and pray

It might come true

Baby, then there wouldn’t be a single thing we couldn’t do.

Wouldn’t it be nice?

Joel M. Kremer, MD, MACR, has engaged in clinical research for the past four decades. He currently leads a not-for-profit research organization, the Corrona Research Foundation.

Joel M. Kremer, MD, MACR, has engaged in clinical research for the past four decades. He currently leads a not-for-profit research organization, the Corrona Research Foundation.

Answers to Riddles

- Are you asleep?

- or

References

- Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York; 2011.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist. 1984:39(4):341–350.

- Seo P. Moonshot: Apollo 11, vaccines & other conspiracies. The Rheumatologist. 2021 Sep 14.

- Kahneman D, Sibony O, Sunstein CR. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment. Little, Brown Spark; 2021.

- Neprash HT, Barnett ML. Association of primary care clinic appointment time with opioid prescribing. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 2;2(8):e1910373.

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press; 2008.

- Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul;73(7):924–939.

- Harrold LR, Harrington JT, Curtis JR, et al. Prescribing practices in a US cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients before and after publication of the American College of Rheumatology treatment recommendations. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Mar;64(3):630–638.

- Atlas J. The amygdala made me do it (opinion). The New York Times. May 12, 2012.

- James W. The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt and Company; 1890.

- Whipple TK. Study Out the Land. University of California Press; 1943.