So what else can you do when your clinic is busy and you have a learner? As described above, patients appreciate in-room presentations. Hearing presentations in the room maximizes your face-to-face time with patients and ensures that you meet supervision guidelines of confirming all elements of the patient’s history. Before using this technique, inform the trainee ahead of time that she will present in front of the patient. Be sure to ask if there is anything especially sensitive you should know before entering the room. You can ensure that the patient confirms data and maximize the interaction by having the trainee stand next to the patient while presenting, referring to the patient as “you,” so that you can make eye contact with both the patient and the learner.

After hearing the data and examining the patient, you can ask the learner to explain her diagnostic considerations and management rationale in front of the patient. This approach enables “dual teaching” of both the learner and the patient. Counseling about medication side effects, or what to look for in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), is educational for both parties. Alternatively, you can adapt your own hybrid OMP model. For example, leave the room for a moment while the patient dresses to discuss medical decision making and give the trainee feedback before concluding the patient visit. If you have concluded in the room, after the patient leaves you can wrap up the visit by making additional teaching points, probing the learner for unanswered questions, and providing feedback on the interaction.

“Active observation” is a teaching technique to use with very early learners, when you are especially busy, or when you want to model an interaction for a trainee. Even a shadowing experience can be made into a productive learning exercise by giving the trainee an observational task during the interaction. For example, you can ask the learner to observe how you collected a rheumatologic history. The learner should take notes, then, after the visit, discuss with you what he observed you doing. You can then highlight any important behaviors or techniques you used that the learner did not notice. In such an interaction, you not only have an opportunity to teach skills and behaviors for effective patient assessment, you also receive feedback on your own patient interactions.

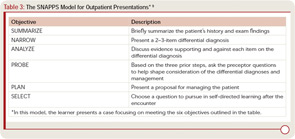

Another outpatient teaching model changes the focus from the exchange of factual information to the expression of thinking behaviors. This learner-driven model, SNAPPS (see Table 3), requires training, primarily on the part of learners, and places responsibility on the learner for acquiring case-generated knowledge.9 In SNAPPS interactions, the learner’s presentation focuses on narrowing a differential diagnosis, analyzing diagnostic possibilities, and asking the preceptor questions, followed by making a patient management plan, then a case-based learning plan. Since this teaching method requires some work for the learner, it is generally used in one or two patient interactions per day, rather than with every patient. When you have limited sessions with a learner and cannot ensure follow up on learning objectives, SNAPPS may not be the ideal teaching model. However, when tested, trainees performing presentations according to the SNAPPS model listed twice as many differential diagnoses, justified them five times more often, and formulated eight times more questions than the traditional presentation group.10

Other Efficiency Solutions

Simultaneously running an efficient clinic and being an effective teacher is challenging, but being efficient and effective makes teaching more satisfying for us, our patients, and our learners. Here are some additional tips to improve teaching efficiency:

- Be organized and set expectations. Devote a few minutes to learning about your learner. Ask about her background in rheumatology, her career plans, and what she hopes to gain from your interaction. Spend time introducing how you would like the day to run by explaining your expectations and any special instructions. Select the patients the house staff will see. Every patient is new to them and, when they only have three half-days of rheumatology during a three-year residency, a few “routine” follow-up visits with RA patients may prove more appropriate than spending an hour and a half with a complicated case of systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Allow the trainee to focus on activities with educational value (for instance, remember that value can come from helping to solve a patient problem by making phone calls). Personally, I find doing my own dictations to be most efficient. Residents dread doing dictations in subspecialty clinics because they are afraid they will forget something or phrase things improperly, and they worry they will get something wrong in the assessment and plan. I find that I can do a dictation in about two minutes that takes a resident 10–12 minutes to do—10–12 minutes that could be spent learning from another patient. To that end, try to make the resident spend as much time learning from the patients as possible.

- Do not allow the resident to perform in-depth “chart biopsies.” In the inpatient setting, with the availability of electronic information, I find that most residents today have read the entire available chart and records and reviewed all available studies before they ever go see the patient. They are often not used to speaking with the patients to get information, which is, of course, one of the most important things we do as rheumatologists. I try not to have residents evaluate patients who are new to me, since it takes me twice as long to confirm the story, and I never feel as though I know those patients well. As stated previously, in most circumstances every patient is new to your trainee. If there are no patients waiting, then have a resident actively observe you performing the history to learn how to do it efficiently.

- Teach in the examination room. I find it most efficient to do everything I can in the examination room. I tell the resident at the beginning of clinic that they will be doing the entire presentation in front of the patient, and that I do nearly all my teaching in the examination room. This approach can take a bit of discipline because it is tempting to hear the resident’s presentation, then examine the patient yourself and continue as though the resident is not there. I try to have the resident go through the whole presentation, including the physical exam, and then ask them what they think is going on and what we should recommend. I then examine the patient myself and invite the resident to re-examine the patient with me. I always ask the patient, “Do you mind if I teach about you for a few minutes?” I have yet to get no for an answer. In my experience, the patients enjoy learning what I am looking for when I examine them, and they will often mention findings they want to show the trainee that I have forgotten about or missed. Generally, the only thing I do outside the patient room is dictate and, once I start dictating, I send the resident in to see the next patient.

- Have a toolbox of effective teaching methods, and choose one based on your learner and available time.

Mold Tomorrow’s Rheumatologists

Working with trainees is an excellent opportunity to increase interest in our field. Given duty hours restrictions, the time trainees have with rheumatologists is limited. To ensure the longevity of our field, it is our job to ensure that trainees have positive learning experiences.

- Be organized.

- Set expectations, and listen to the learner’s needs upfront.

- Keep your learner’s level in mind as you select patients for him or her to see.

- Do in-room presentations whenever possible.

- Focus on the educational value of activities in the clinic, and remember that multiple competencies are addressed with each patient encounter.

Since learners represent the next generation in medicine, we must work in the present to be as strong and effective teachers as possible. The time learners spend with patients can no doubt be entertaining. As my experience indicates, it also can create value for patients now and advance our field in the future. If we devote some time and consideration to our teaching methods today, we can help attract an engaged and excited group of future rheumatologists to our field.