“The resident’s purpose is to entertain the patient until I can get there,” I said decisively, suppressing a smile as I awaited the audience’s reaction. I was attending our Department of Medicine’s inaugural “Teach the Teachers” faculty development workshop held last June on a hot summer afternoon. The sun was shining, but we were in a drab and dark classroom. At this workshop, we were discussing outpatient teaching when a colleague asked, “How do you function efficiently when you have a resident with you?” Although I was intending to be facetious to capture my audience’s attention, my comment had a serious side. The organizer (who, I think, wanted to see how serious I really was about this issue) liked the comment and afterwards invited me to speak at the next workshop on efficiency with learners in the outpatient setting.

Reflection on the role of learners in the clinic, and how to maximize their learning potential along with my efficiency, led me to examine how I can improve the clinic experience for myself and the learners in my office. In this article, I will describe my thinking.

The Challenge

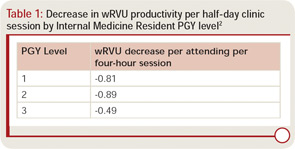

The results of a recent workforce survey mentioned in the June 2010 issue of The Rheumatologist stated that academic rheumatologists see, on average, 44 patients each week in 16 clinic hours.1 With an average of 11 patients per session, teaching rheumatology effectively can be very challenging. Generally speaking, learners slow you down. In one published report, each resident in a general medicine clinic decreased production for the half day by about 0.8 wRVUs [relative value units] (see Table 1).2

Every person in a clinical teaching interaction has different goals. Your patient expects to see you, be appropriately assessed and managed, and hear answers to his or her questions. Learners must acquire the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for competent practice and to pass certification examinations. The learner needs and expects performance feedback. You want to provide excellent patient care, efficiently meet productivity goals, impart knowledge, and even inspire learners to become rheumatologists. Successfully meeting these goals requires organization and planning! Using efficient outpatient teaching techniques can help ensure positive outcomes for all three stakeholders: learners gain knowledge; patients receive added attention, insight into their conditions, and satisfaction from helping teach tomorrow’s providers; and you, the teaching rheumatologist, can gain the satisfaction of successfully teaching.

The Data

The medical education literature supports experiential learning. Residents learn well through direct practice (e.g., learning arthrocentesis on models), faculty role modeling, and a consistent relationship between the resident and the teacher.3 In our current learning environment, continuity of resident and attending pairs in subspecialty clinic may be unusual, making it difficult to understand trainees’ learning needs. Although a survey analysis revealed only 40% agreement between the faculty and housestaff regarding the trainee’s top priority learning need, the trainee’s satisfaction with a faculty interaction appeared independent of whether the perceived learning needs were aligned.4 This result indicates that any case-based teaching is beneficial. A study by Laidley et al suggested that, in supervisory interactions, residents most commonly seek validation of their treatment plans.4 Other common learning needs include learning about therapy, differential diagnosis, clarification of physical findings, and choosing diagnostic testing. Faculty goals in any interaction are more often focused on assessing the trainee’s performance and recommending further study.

Many of us think of bedside teaching as an effective inpatient teaching technique. In addition, bedside teaching works in the clinic and improves efficiency. A randomized trial evaluated the impact of doing internal medicine continuity clinic “sign-outs” either in the patients’ rooms or entirely in a conference room. There was no difference between groups in: 1) the amount of teaching done by the supervising doctor; 2) whether the attending physician changed the impression or plan; or 3) patient satisfaction. However, patients preferred hearing bedside discussions of their cases to not hearing these discussions. Although 10% of residents reported feeling uncomfortable doing the entire patient presentation in the examination room, the patients felt more comfortable with the interaction in this setting.5

To give the data perspective, I informally surveyed several internal medicine residents at my institution, Duke University Health System, about their subspecialty clinic experiences. These residents indicated they liked independently seeing patients initially and devising preliminary impressions and plans. They value being taught during the patient encounter and having faculty spend time pointing out and practicing physical examination skills particular to rheumatology—all consistent with adult learning theory (adults learn best when addressing a problem in real time). The residents I surveyed universally disliked feeling they were just “tagging along.” They like to be helpful. They do not mind dictating notes when they participate in the visits and help to develop assessments and plans. However, they dislike dictating when they feel their only purpose is to document the visit, especially when they did not even understand the rationale for assessment and treatment decisions.

Efficient Outpatient Teaching Methods, Evaluation and Management Guidelines Overview

The traditional clinical teaching encounter is directed primarily towards patient care, not towards meeting learners’ needs. Traditionally, attendings’ questions serve to clarify clinical data. Teaching occurs as mini-lectures rather than discussion, and the trainee receives little or no feedback on her clinical reasoning skills, perhaps because reasoning skills are not evident in such interactions. Rather, the trainee who appears most competent is the one who best presents data. Unfortunately, such interactions, which neither explore nor reward expressing uncertainty and thinking through diagnostic possibilities, do not promote growth of the trainee as a practitioner.

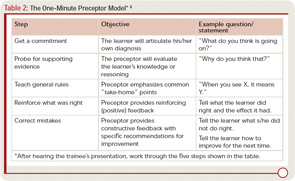

Fortunately, a few skills can help you both review the data necessary to care for your patients and help you be attentive to the learner’s needs and development of clinical reasoning through effective feedback. One widely referenced outpatient teaching method is the “One-Minute Preceptor” (OMP) model, a learner-centered strategy for efficient teaching.6 The OMP allows discussion of patient data to provide patient care while ensuring that the preceptor–trainee interaction focuses on the thought required to derive clinical conclusions (see Table 2). In this model, the preceptor listens to the trainee’s presentation and then asks the trainee to articulate a diagnosis. The trainee is asked to discuss and support this diagnosis. After this discussion, the preceptor makes a related teaching point then provides positive and constructive feedback on the trainee’s clinical reasoning. Through listening to a trainee justify his or her conclusions, the preceptor can assess the trainee’s clinical abilities. The teaching interaction concludes with constructive feedback on what the trainee did well and what the trainee can improve. When compared to traditional teaching in published studies, the OMP allows preceptors to diagnose patient’s problems equally or better, preceptors can rate students with greater confidence, and preceptors rate OMP encounters as more effective and efficient. Students rate the OMP as a more effective teaching strategy than traditional teaching.7,8

So what else can you do when your clinic is busy and you have a learner? As described above, patients appreciate in-room presentations. Hearing presentations in the room maximizes your face-to-face time with patients and ensures that you meet supervision guidelines of confirming all elements of the patient’s history. Before using this technique, inform the trainee ahead of time that she will present in front of the patient. Be sure to ask if there is anything especially sensitive you should know before entering the room. You can ensure that the patient confirms data and maximize the interaction by having the trainee stand next to the patient while presenting, referring to the patient as “you,” so that you can make eye contact with both the patient and the learner.

After hearing the data and examining the patient, you can ask the learner to explain her diagnostic considerations and management rationale in front of the patient. This approach enables “dual teaching” of both the learner and the patient. Counseling about medication side effects, or what to look for in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), is educational for both parties. Alternatively, you can adapt your own hybrid OMP model. For example, leave the room for a moment while the patient dresses to discuss medical decision making and give the trainee feedback before concluding the patient visit. If you have concluded in the room, after the patient leaves you can wrap up the visit by making additional teaching points, probing the learner for unanswered questions, and providing feedback on the interaction.

“Active observation” is a teaching technique to use with very early learners, when you are especially busy, or when you want to model an interaction for a trainee. Even a shadowing experience can be made into a productive learning exercise by giving the trainee an observational task during the interaction. For example, you can ask the learner to observe how you collected a rheumatologic history. The learner should take notes, then, after the visit, discuss with you what he observed you doing. You can then highlight any important behaviors or techniques you used that the learner did not notice. In such an interaction, you not only have an opportunity to teach skills and behaviors for effective patient assessment, you also receive feedback on your own patient interactions.

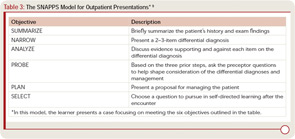

Another outpatient teaching model changes the focus from the exchange of factual information to the expression of thinking behaviors. This learner-driven model, SNAPPS (see Table 3), requires training, primarily on the part of learners, and places responsibility on the learner for acquiring case-generated knowledge.9 In SNAPPS interactions, the learner’s presentation focuses on narrowing a differential diagnosis, analyzing diagnostic possibilities, and asking the preceptor questions, followed by making a patient management plan, then a case-based learning plan. Since this teaching method requires some work for the learner, it is generally used in one or two patient interactions per day, rather than with every patient. When you have limited sessions with a learner and cannot ensure follow up on learning objectives, SNAPPS may not be the ideal teaching model. However, when tested, trainees performing presentations according to the SNAPPS model listed twice as many differential diagnoses, justified them five times more often, and formulated eight times more questions than the traditional presentation group.10

Other Efficiency Solutions

Simultaneously running an efficient clinic and being an effective teacher is challenging, but being efficient and effective makes teaching more satisfying for us, our patients, and our learners. Here are some additional tips to improve teaching efficiency:

- Be organized and set expectations. Devote a few minutes to learning about your learner. Ask about her background in rheumatology, her career plans, and what she hopes to gain from your interaction. Spend time introducing how you would like the day to run by explaining your expectations and any special instructions. Select the patients the house staff will see. Every patient is new to them and, when they only have three half-days of rheumatology during a three-year residency, a few “routine” follow-up visits with RA patients may prove more appropriate than spending an hour and a half with a complicated case of systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Allow the trainee to focus on activities with educational value (for instance, remember that value can come from helping to solve a patient problem by making phone calls). Personally, I find doing my own dictations to be most efficient. Residents dread doing dictations in subspecialty clinics because they are afraid they will forget something or phrase things improperly, and they worry they will get something wrong in the assessment and plan. I find that I can do a dictation in about two minutes that takes a resident 10–12 minutes to do—10–12 minutes that could be spent learning from another patient. To that end, try to make the resident spend as much time learning from the patients as possible.

- Do not allow the resident to perform in-depth “chart biopsies.” In the inpatient setting, with the availability of electronic information, I find that most residents today have read the entire available chart and records and reviewed all available studies before they ever go see the patient. They are often not used to speaking with the patients to get information, which is, of course, one of the most important things we do as rheumatologists. I try not to have residents evaluate patients who are new to me, since it takes me twice as long to confirm the story, and I never feel as though I know those patients well. As stated previously, in most circumstances every patient is new to your trainee. If there are no patients waiting, then have a resident actively observe you performing the history to learn how to do it efficiently.

- Teach in the examination room. I find it most efficient to do everything I can in the examination room. I tell the resident at the beginning of clinic that they will be doing the entire presentation in front of the patient, and that I do nearly all my teaching in the examination room. This approach can take a bit of discipline because it is tempting to hear the resident’s presentation, then examine the patient yourself and continue as though the resident is not there. I try to have the resident go through the whole presentation, including the physical exam, and then ask them what they think is going on and what we should recommend. I then examine the patient myself and invite the resident to re-examine the patient with me. I always ask the patient, “Do you mind if I teach about you for a few minutes?” I have yet to get no for an answer. In my experience, the patients enjoy learning what I am looking for when I examine them, and they will often mention findings they want to show the trainee that I have forgotten about or missed. Generally, the only thing I do outside the patient room is dictate and, once I start dictating, I send the resident in to see the next patient.

- Have a toolbox of effective teaching methods, and choose one based on your learner and available time.

Mold Tomorrow’s Rheumatologists

Working with trainees is an excellent opportunity to increase interest in our field. Given duty hours restrictions, the time trainees have with rheumatologists is limited. To ensure the longevity of our field, it is our job to ensure that trainees have positive learning experiences.

- Be organized.

- Set expectations, and listen to the learner’s needs upfront.

- Keep your learner’s level in mind as you select patients for him or her to see.

- Do in-room presentations whenever possible.

- Focus on the educational value of activities in the clinic, and remember that multiple competencies are addressed with each patient encounter.

Since learners represent the next generation in medicine, we must work in the present to be as strong and effective teachers as possible. The time learners spend with patients can no doubt be entertaining. As my experience indicates, it also can create value for patients now and advance our field in the future. If we devote some time and consideration to our teaching methods today, we can help attract an engaged and excited group of future rheumatologists to our field.

Dr. Criscione-Schreiber is assistant professor of medicine–rheumatology and immunology, at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

References

- The ACR Benchmark Survey Results. The Rheumatologist. 2010;4(6):21.

- Johnson T, Shah M, Rechner J, King G. Evaluating the effect of resident involvement on physician productivity in an academic general internal medicine practice. Acad Med. 2008;83:670-674.

- Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2217-2225.

- Laidley TL, Braddock CH, 3rd, Fihn SD. Did I answer your question? Attending physicians’ recognition of residents’ perceived learning needs in ambulatory settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:46-50.

- Anderson RJ, Cyran E, Schilling L, et al. Outpatient case presentations in the conference room versus examination room: results from two randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2002;113:657-662.

- Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:419-424.

- Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the one-minute preceptor model for diagnosing the patient and the learner: Proof of concept. Acad Med. 2004;79:42-49.

- Irby DM, Aagaard E, Teherani A. Teaching points identified by preceptors observing one-minute preceptor and traditional preceptor encounters. Acad Med. 2004;79:50-55.

- Wolpaw TM, Wolpaw DR, Papp KK. SNAPPS: A learner-centered model for outpatient education. Acad Med. 2003;78:893-898.

- Wolpaw T, Papp KK, Bordage G. Using SNAPPS to facilitate the expression of clinical reasoning and uncertainties: A randomized comparison group trial. Acad Med. 2009;84:517-524.