Image Credit: conejota/shutterstock.com

Recognizing the need to provide guidance on the current disparate management of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), in collaboration with the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), recently published the first international set of recommendations for the screening, treatment and management of PMR.1,2

Specifically, the recommendations offer guidance on the use of glucocorticoids (GCs) (e.g., initial dose, strategies for tapering off), the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the duration of treatment.

Acknowledging the marked, non-evidence-based variations in the use of these therapies is particularly important because of the high rates of GC-related side effects in people with PMR, according to Eric Matteson, MD, chair of rheumatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and the ACR co-principal investigator of the guideline development project.

Dr. Matteson

Studies show that approximately 85% of patients with PMR experience GC-related side effects. Further, up to 45% of patients with PMR don’t respond adequately to GCs within three to four weeks, and relapses and long-term dependency on these agents are common.1

The EULAR co-principal investigator of the guideline project, Bhaskar Dasgupta, MD, Department of Rheumatology at Southend University Hospital, Prittlewell Chase in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, U.K., emphasizes the need to address the variation in GC use, citing the narrow risk–benefit ratio of steroids to treat PMR and the common GC-related side effects, as well as the fact that PMR is the most common reason for the use of long-term steroid therapy.

Recommendations

The recommendations highlight evidence that supports reducing the dose and length of initial and maintenance GC therapy, as well as data on the efficacy of other agents. The recommendations are based on a systematic review of the literature of relevant studies published between January 1970 and April 2014.1

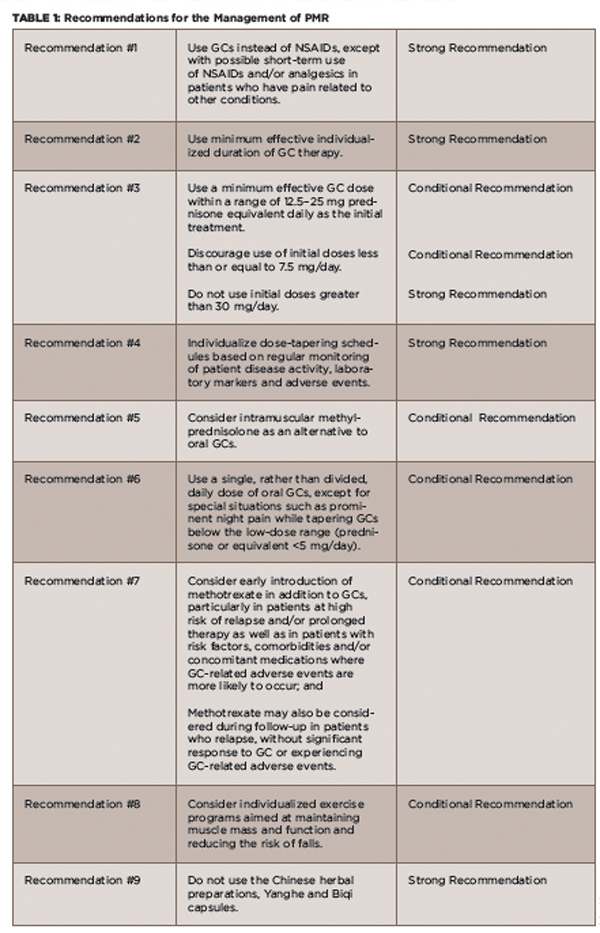

(click for larger image)

TABLE 1: Recommendations for the Management of PMR

Definitions: GC = glucocorticoid; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Strong Recommendation = Ample evidence of a large benefit with no or little risk; Conditional Recommendation = Little or modest evidence of benefit, and/or the benefit did not greatly outweigh the risks.

Source: Adapted from the ACR Press Release 20152

The multidisciplinary and international panel used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to evaluate the evidence. The direction (i.e., in favor of or against) and strength (i.e., strong or conditional) of the recommendations are based on the quality of the evidence, the balance between desirable and undesirable effects, values and preferences of the patients and clinicians, and resource use.1 (A more complete description of the methods used in this study can be found online.)

In all, the ACR and EULAR jointly developed nine recommendations that cover a number of treatment-related issues, including initial GC dose and tapering regimens, risk factor assessment for GC use, use of intramuscular GCs, DMARDs, the role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and non-pharmacologic interventions (see Table 1). Issues related to patient access to medical care, specialist referral and investigations of patients under treatment are also covered.

Along with these recommendations, the panel of investigators formulated what they call eight overarching principles that reflect the current standards of clinical care of PMR—including patient and clinician values and preferences—that the panel determined were important for patients to know (see Table 2). These overarching principles, general in nature and design, highlight the importance of patient education regarding PMR and their ability to rapidly and easily access physician advice and support as needed.

Implementation

A change in habits and attitudes is critical to implementing these recommendations,

Dr. Dasgupta

according to Dr. Dasgupta. “These [recommendations] are the first steps to introduce the scientific method in the management of this condition,” he says, emphasizing that clinicians need to accept flexible dosing for PMR.

Dr. Dasgupta says the current recommendations are part of a continuum of activity over the past several years to address the need for better uniformity and standards in the management of PMR. Efforts have included a commentary published in Arthritis & Rheumatism in 2006 highlighting the need for better guidance and standards, and subsequent guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritis issued in 2010 by the British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology, as well as the EULAR/ACR classification criteria for PMR issued in 2012.3-6

(click for larger image)

TABLE 2: Overarching Principles for PMR Management

Source: Adapted from Dejaco et al 20151

With the new recommendations, Dr. Dasgupta stresses the importance of carefully assessing each patient with suspected PMR and tailoring treatment according to the specific individual. This includes individualizing steroid dose, a gradual tapering of steroids, early introduction of DMARDs, such as methotrexate, to avoid NSAIDs and the occasional need for intramuscular methyprednisolone in patients who require lower cumulative doses. He also emphasizes the need to include individualized exercise programs (e.g., range-of-movement exercises), as well as patient education and participation in clinical research.

Dr. Matteson emphasizes that most patients with PMR can be managed successfully with modest (i.e., not exceeding 25 mg/day) initial doses of prednisone. “Every effort should be made to reduce the glucocorticoid burden by careful dose reduction and consideration of glucocorticoid-sparing therapy, [which is] currently methotrexate,” he says.

For Michael Lucke, MD, staff rheumatologist at the Lupus Center for Excellence, West Penn Allegheny Health System in Pittsburgh, the conditional recommendation to use methotrexate early in the management of PMR was surprising. “While often used to treat PMR, the data for methotrexate use [have] been contradictory, and trials have included small numbers of patients,” he says. “Further research on high numbers of patients on different doses of methotrexate will be required to advance methotrexate to a stronger recommendation.”

Saying that the recommendation for the addition of methotrexate was a little vague, Petros Efthimiou, MD, associate chief of rheumatology at New York Methodist Hospital and associate professor of Medicine and Rheumatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, adds that “the decision to use methotrexate is left to the clinical acumen of the physician for each individual case.”

Dr. Matteson acknowledges that some practitioners will not agree on the potential benefit of methotrexate and says that he recognizes that if or when methotrexate should be used in the course of disease is not yet settled. Others, he says, may not agree that NSAIDs or anti-tumor necrosis factor agents should not be used to manage PMR, despite their poor efficacy as found in the evidence.

Dr. Matteson also stresses that, characteristic of all guidelines, the recommendations offered are just that, recommendations. “As with all guidelines, the individual patient’s situation and needs should always be taken into account,” he adds.

Roadmap for Primary Care Physicians

The recommendations were developed not just to provide guidance to specialists about optimal care of PMR patients, but because “there is a lot of confusion among non-specialists about the proper management of PMR, and access to rheumatologists is not always readily available,” says Dr. Efthimiou. “These recommendations address this unmet need and provide a roadmap for primary care physicians to treat PMR and, hence, avoid delays in treatment.”

Because most patients with PMR are diagnosed and treated in the primary care setting, Dr. Matteson hopes the guidelines will be widely disseminated and adopted by all practitioners.

“Importantly, the guidelines emphasize the need for correct diagnosis and recognize the role of specialty care by rheumatologists in the management of these patients, especially for difficult and unusual cases,” he says.

Also emphasizing that primary care physicians are usually the first physicians to assess PMR in a patient, Dr. Lucke says, “the guidelines can help avoid common pitfalls of starting prednisone at too high a dose, as well as tapering prednisone too rapidly.”

“However, the guidelines also acknowledge that individual dose-tapering schedules are needed and that there is no ‘one size fits all’ dose in management of this condition,” he adds.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Dejaco C, Singh YP, Perel P, et al. 2015 recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Oct;67(10):2569–2580.

- ACR releases new publications focused on polymyalgia rheumatica and gout [news release]. Atlanta: American College of Rheumatology. 2015 Sep 10.

- Dasgupta B, Hutchings A, Matteson EL. Polymyalgia rheumatica: The mess we are now in and what we need to do about it. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug 15;55(4):518–520.

- Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, et al. BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1594–1597.

- Dasgupta B, Cimmino MA, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. 2012 Provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Apr;71(4):484–492.

- Dasgupta B, Cimmino MA, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. 2012 provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2012 Apr;64(4):943–954.