kilukilu / shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—When it comes to correctly diagnosing joint pain in children, “things take time,” said Michael L. Miller, MD, quoting Danish physicist and poet Piet Hein. Children with pain but normal physical examinations may need to return to the clinic for repeat evaluation over several months. “I often tell parents that laboratory tests may help in diagnosis, but they’re a guide in children and adolescents. I say, ‘In the absence of a diagnosis, we are in a monitoring phase.’”

During Arthralgia in the Pediatric Patient, a session at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, Dr. Miller, clinical practice director, Division of Rheumatology, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago, shared his experience in managing children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes and communicating with children and parents.

When a physical examination is unremarkable, rheumatologists should ask about the child’s recent history of school absences due to pain, which will quickly distinguish children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes from those who have early juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). “Children with [musculoskeletal pain syndromes] are often anxious about returning to school, while children with JIA are often depressed about missing school,” he said.

Hyperextensibility

Dr. Miller

One common diagnosis in children who present with joint pain but a normal physical examination is hyperextensibility arthralgia, said Dr. Miller. Often, these patients have low-titer, positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) for unknown reasons. ANA is a screening rather than a diagnostic test for rheumatic diseases, because it has high sensitivity, but low specificity. Hyperextensibility often occurs in the metacarpophalangeal joints, thumbs, elbows and knees.

“Most of these patients do well. Some need physical therapy, but they should not be missing school. School absences suggest the possibility of a pain syndrome,” Dr. Miller said.

Follow-up examinations may reveal an underlying diagnosis. “I’ve seen a number of children with rheumatic diseases who weren’t diagnosable when they were first seen, including some with hyperextensible joints who later developed enthesitis,” he said.

Cancer & Infections

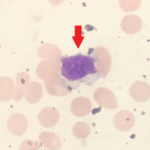

Malignancies, such as acute lymphocytic leukemia, in children and adolescents may also cause pain around the joints. Neutropenia can be a warning sign of leukemia, and imaging may be helpful.

Dr. Miller shared a case of a 5-year-old patient who was ultimately diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia. The patient presented with wrist pain, but no joint swelling or loss of motion. “Pain was intense, and the child was anemic and had a low neutrophil count. I point out to residents that we don’t typically see neutropenia in children presenting with joint pain. Although neutropenia can result from a transient viral infection, leukemia needs to be considered. X-rays of the affected area can be helpful,” he said. He pointed out an X-ray finding associated with leukemia in this patient: a zone of rarefraction (i.e., reduction in neutrophil density).

Examining a complete blood count can offer assistance in diagnosis, said Dr. Miller. Neutropenia and lymphocytosis are atypical in children with rheumatic diseases. Because activated lymphocytes migrate out of circulation to target organs, lymphopenia is more common, such as in children with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Decreased counts in all cell lines raise the possibility of secondary macrophage activation syndrome, he noted.

Infections may precede arthralgias in children. “The differential diagnosis includes a transient, post-infectious arthritis typically lasting less than six weeks—although, I’ve seen it last as long as three months,” said Dr. Miller. Bacterial infections, such as enteritis and urinary tract infections, may trigger reactive arthritis, from which a small percentage of children will develop chronic arthritis.

Juvenile Arthritis

Often, rheumatologists use the 1997 classification criteria to diagnose children with JIA, a group of diseases that lasts for six weeks or longer in children ages 16 years or younger. These diseases include systemic JIA, oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) and undifferentiated arthritis.1

In systemic JIA, “there may be a delay before synovitis develops, often up to several months,” Dr. Miller said. Children with oligoarticular JIA may also have arthralgias for weeks or months before synovitis develops, as well as atrophy of extensor muscles. “These children may require splinting. This is a group in whom uveitis occurs—often asymptomatic,” he said.

Children with polyarticular JIA often have arthritis that affects the small joints in their hands and cervical spine, and typically have a chronic disease course. A subset of children with clinical oligoarticular arthritis exists, and these children have a more aggressive, chronic disease course, said Dr. Miller. “None of the JIA subtypes are homogenous. Children with JIA may need physical or occupational therapy and also splinting.”

‘School absences suggest the possibility of a pain syndrome.’ —Dr. Miller

Children with enthesitis may present with arthritis followed by enthesitis or pain over the attachment of tendons or ligaments to bone, such as over the Achilles tendons or plantar fasciae. Some children with other JIA subtypes can also present with enthesitis in addition to synovitis, Dr. Miller noted.

“It’s actually rare that we see advanced spine disease resulting in ankylosis in children with [enthesitis-related arthritis]. I’ve only seen this a couple of times in boys who were HLA-B27 positive,” said Dr. Miller. “Enthesitis may take months or even years to manifest.”

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an effective tool to detect joint erosions and bone marrow edema in children with enthesitis-related arthritis. And there may be a family history of the disease, he said.

Laboratory Tests

Differential diagnosis helps determine which laboratory tests to order, said Dr. Miller. Consider SLE in differential diagnosis for children who present with arthralgias as well.

Up to half of children with active synovitis and juvenile arthritis have normal erythrocyte sedimentation rates, he stressed.2 Over time, repeat blood tests may help diagnose the cause of unexplained pain.

“I’ve had patients with normal differentials who then had neutropenia on a subsequent test. One child had leukemia. Children with leukemia don’t always have abnormal blood tests, so it may be helpful to repeat these tests over a few months while they’re having symptoms. There are cases of children with leukemia presenting with a definite synovitis, but usually the pain is over the metaphysis,” said Dr. Miller.

Fevers & Back Pain

Children with arthralgias but normal joint exams may present with other symptoms, such as prolonged fevers. In these cases, patients may need to be admitted to the hospital for thorough malignancy and infection workups, Dr. Miller said. An echocardiogram helps detect other causes of pain with fevers and other symptoms, such as non-specific rashes. These include coronary arterial aneurysm, Kawasaki disease, thickening of the mitral valve or pericardial effusion in children with systemic JIA. Depending on the particular presentation, auto-inflammatory diseases may need to be considered.

“Even if one doesn’t hear a heart murmur, but the patient has adenopathy, fevers and non-specific rash—along with arthralgias—think about [ordering] an echocardiogram. It’s a good routine test,” said Dr. Miller.

Back pain has a broad differential diagnosis in children. Dr. Miller shared a case of a child with persistent, moderate to severe back pain and trouble walking, but a normal examination and X-rays. An MRI revealed intraspinal metastatic lesions. This patient was later diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Children cannot always localize back pain. “I often can’t use a child’s or parent’s reported history to determine what part of the spine to image. I have seen abnormalities in the MRI not located where they were reporting the pain,” Dr. Miller said.

Back pain may occur in spondylolisthesis; infections, such as intraspinal abscess or vertebral osteomyelitis; tethered cord; syrinx; Chiari malformation; spinal cord tumors; or acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Children with back pain who cannot walk should always be admitted to the hospital for further evaluation, said Dr. Miller. Possible diagnoses associated with these symptoms include early septic arthritis, early osteomyelitis, spinal abscess or tumor, as well as physical or sexual abuse.

Use structured interviews, and collaborate with social workers and mental health professionals to screen for abuse or psychiatric problems that cause pain in children. Targeted MRI has replaced bone scans in identifying potential malignancies that may cause walking problems in children, followed by biopsies to confirm the diagnosis.

Weakness

Proximal muscle weakness may be a sign of inflammatory muscle disease. However, it is worth asking adolescents if they lift weights, because this can elevate creatine phosphokinase levels, Dr. Miller said.

“Laboratory and muscle biopsies will exclude muscular dystrophy,” he said. Creatine phosphokinase is an important test for children with weakness. Elevated levels may result from dermatomyositis or polymyositis. Marked elevation suggests muscular dystrophy. Severe elevation may mean rhabdomyolysis. “If [creatine phosphokinase] is normal, consider chronic inflammatory muscle disease or other non-inflammatory causes.”

Pain Management

Management of arthralgias includes treating the disease, as well as non-medical approaches, such as physical or occupational therapy, guided imagery and mindfulness meditation, said Dr. Miller. Children with depression or joint pain caused by abuse should be referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Physical medicine specialists may also help with pediatric pain management. Avoid pain medications and corticosteroids in children, if possible, and use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) cautiously. Dr. Miller suggested alternating two weeks on NSAIDs with two weeks off, particularly if children want to get back to school during a monitoring phase.

How should rheumatologists communicate with parents about their child’s arthralgias, especially when diagnosis takes time?

“I do tell [parents] that I can’t make a diagnosis at this time based on the lab results and examination. I don’t say, ‘There is nothing wrong with your child,’” Dr. Miller said. “However, I do let the parents know that the child should return to school. I tell parents that we need to monitor their child for physical changes, and psychological examinations may be needed, as well. I don’t say goodbye, or ‘I don’t need to see your child again.’”

The evaluation of a child with arthralgias but a normal physical examination provides a challenge to rheumatologists. The possible causes of these diagnoses range from psychiatric problems to rheumatic diseases to malignancies, and the opportunity to provide the right care to these patients is highly rewarding, Dr. Miller said.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.

References

- Petty RE, Southwood TR, Baum J, et al. Revision of the proposed classification criteria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Durban, 1997. J Rheumatol. 1998 Nov;25(10):1991–1994.

- Giannini EH, Brewer EJ. Poor correlation between the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and clinical activity in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1987 Jun;6(2):197–201.