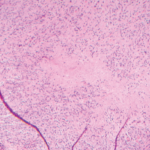

CVID, the most common form of immune deficiency except for selective IgA deficiency, usually presents either early between 1 and 5 years old, or later between the ages of 18 and 25, but in some patients, it may not be recognized until their fourth or fifth decade, Dr. Chatham said. It most commonly manifests with frequent respiratory tract infections, bronchiectasis and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease, and/or granulomatous lesions that can affect any organ.

Dr. Chatham cautioned that the pathology of these lesions is indistinguishable from sarcoidosis, but that active sarcoidosis is usually associated with hypergammaglobulinemia. “If you don’t see high IgG levels in that setting, it might be CVID,” he said.

Dr. Chatham suggested using a rule of 500s to mitigate the risk of immune deficiencies associated with immunosuppressive treatment.

The diagnostic assessment for CVID involves trying to exclude other primary immune deficiencies by looking at B and T cell subsets and by genetic testing, although no abnormalities have been identified in a majority of CVID patients.

The most telling sign is an IgG count below 650 mg/dL, but Dr. Chatham said this assessment can be tricky, in part because chronic immunosuppression or corticosteroid use can also lower IgG levels. However, in such settings pneumococcal vaccine responses should remain intact. Clinicians should also be aware that patients with a normal IgG range could still have subclass deficiencies.

CVID patients with lupus or Sjögren’s syndrome—diseases typically linked with hypergammaglobulinemia—could have IgG levels in the normal or low-normal range, he cautioned.

“The take-home message here is to consider CVID in a lupus patient with normal or low-normal IgG levels who has a relevant infection history,” he said, “and if they happen to be in [a] particular Caucasian demographic.” Scottish, north English and Irish people are disproportionately affected, he said.

Managing Risk

Clinicians managing CVID should try to adjust the dosing of immunosuppressive therapy affecting phagocytic cell functions as disease activity allows. And they can use IVIG and antibiotics as preventive interventions, he said.

“You want to use therapeutic approaches that are the least likely to compromise phagocytic cell functions. So if you have a patient with classic RA, for example, who happens to have CVID, rather than put that patient on a TNF inhibitor, you might want to consider something that doesn’t impair phagocytic cell function, such as rituximab.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.