Ypres is an ancient Belgian town that sits at the crossroads of Europe. It was once dominated by one of the largest Gothic civil buildings in Europe, Cloth Hall, a medieval textile marketplace constructed in the 13th century. Its reputation as a flourishing textile trading center has been immortalized by the word diaper, derived from the French d’ypres and the Middle English, diaper.1 Nestled between France and Germany, it has long witnessed military conflict, having been raided by the Romans in the first century BC, captured by Crusaders in the 14th century and fought for by the French three centuries later. At the start of World War I in 1914, Belgium proclaimed its neutrality.

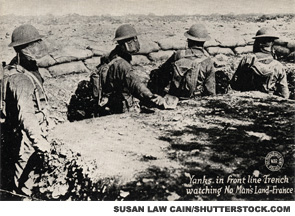

This did not prevent the Imperial German Army from sweeping across Belgium en route to an invasion of France. However, at Ypres, the Germans encountered fierce resistance from French, Belgian, British and Commonwealth forces who literally dug themselves into the ground. The fatalities on both sides were staggering; nearly a half million men died over the course of three major battles fought over control of the town. In the battle of Neuve Chapelle, when the British stormed the German trenches, more shells were fired in the opening 35-minute artillery barrage than were used during the entire Boer War, demonstrating the “terrifying transformation of the nature of war” in just 15 years.2 Not only were the instruments of war far more deadly, the ways that the Great War was fought contributed to the bloodshed and the staggering death toll. Paradoxically, concentrating troops in the trenches that were dug to protect them from the powerful weaponry also made them highly vulnerable to attack by the increasingly accurate, longer range artillery fire and by the release of lethal gases.

What was medicine’s role in all this mayhem? A British reporter described this ghastly scene from a visit to a casualty clearing station: “Men with chunks of steel in their lungs and bowels vomiting great gobs of blood, men with legs and arms torn from their trunks, men without noses, and their brains throbbing though open scalps, men without faces.”3

What could a doctor accomplish in this chaos and madness except to try and stanch the bleeding, patch the smaller wounds and hold the hands of the dying? Yet amidst this dark abyss toiled physicians and surgeons, whose timely observations of pain and suffering have taught us about the complexities of the human condition.