Ypres is an ancient Belgian town that sits at the crossroads of Europe. It was once dominated by one of the largest Gothic civil buildings in Europe, Cloth Hall, a medieval textile marketplace constructed in the 13th century. Its reputation as a flourishing textile trading center has been immortalized by the word diaper, derived from the French d’ypres and the Middle English, diaper.1 Nestled between France and Germany, it has long witnessed military conflict, having been raided by the Romans in the first century BC, captured by Crusaders in the 14th century and fought for by the French three centuries later. At the start of World War I in 1914, Belgium proclaimed its neutrality.

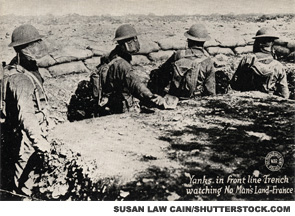

This did not prevent the Imperial German Army from sweeping across Belgium en route to an invasion of France. However, at Ypres, the Germans encountered fierce resistance from French, Belgian, British and Commonwealth forces who literally dug themselves into the ground. The fatalities on both sides were staggering; nearly a half million men died over the course of three major battles fought over control of the town. In the battle of Neuve Chapelle, when the British stormed the German trenches, more shells were fired in the opening 35-minute artillery barrage than were used during the entire Boer War, demonstrating the “terrifying transformation of the nature of war” in just 15 years.2 Not only were the instruments of war far more deadly, the ways that the Great War was fought contributed to the bloodshed and the staggering death toll. Paradoxically, concentrating troops in the trenches that were dug to protect them from the powerful weaponry also made them highly vulnerable to attack by the increasingly accurate, longer range artillery fire and by the release of lethal gases.

What was medicine’s role in all this mayhem? A British reporter described this ghastly scene from a visit to a casualty clearing station: “Men with chunks of steel in their lungs and bowels vomiting great gobs of blood, men with legs and arms torn from their trunks, men without noses, and their brains throbbing though open scalps, men without faces.”3

What could a doctor accomplish in this chaos and madness except to try and stanch the bleeding, patch the smaller wounds and hold the hands of the dying? Yet amidst this dark abyss toiled physicians and surgeons, whose timely observations of pain and suffering have taught us about the complexities of the human condition.

Through the ages, physicians have been at the warrior’s side, offering rudimentary forms of first aid medicine. Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson, a British naval commander, is credited with promoting a revolution in disease control in the military, perhaps due to his personal lengthy list of medical maladies, including yellow fever, and the loss of one eye and an arm.4 Sadly, since Nelson’s time, there have been countless opportunities for physicians and surgeons to hone their battlefield skills.

Death by Infection

Until WWI, most wartime casualties were caused by infections. The lack of proper antisepsis guaranteed that even the most trivial battlefield injury could become fatal. Poor sanitation, cramped living spaces and malnutrition promoted transmission of infectious disease vectors. Cholera, typhoid, streptococcus and a host of enteric bacteria preyed on their hosts’ weakened immune systems. Diarrhea, dysentery and rheumatic fever were among the most prevalent medical problems throughout the American Civil War—and probably throughout all wars up to that time. Not all of the afflicted died. In fact, many survived, and some of them experienced what we now consider to be forms of reactive arthritis. For example, with more than 2 million cases of diarrheal illnesses and 100,000 cases of urethritis reported, it is estimated that there may have been about 30,000 cases of reactive arthritis among the Union troops.5

Bacteria don’t choose sides in war; they are equal-opportunity infectors. In 1864, Confederate Army General Robert E. Lee contracted a throat infection,“which settled into inflammation of the pericardium.”5 He subsequently complained of chronic joint and back pain. Whether this pain was a manifestation of a post-streptococcal arthritis is not clear, but it affected his ability to lead his army and may have indirectly influenced the outcome of a major battle.

During May 1864, following a bloody conflict against the Army of the Potomac near Chancellorsville, Va., Lee was in so much pain from his “rheumatism” that he allowed himself to be taken for a brief reconnaissance mission in a carriage, rather than riding horseback. He realized that his adversary, General Ulysses Grant, had been forced to split his troops, making them vulnerable to counterattack by Confederate forces. But this opportunity began to fade as the Union battalions entrenched while Lee’s illness worsened and he became bedridden. He could not be afield to direct affairs himself, and, as timing would have it, several of his senior commanders fell ill with similar symptoms. Lacking leadership, the Confederate Army lost a precious opportunity to bisect the Union forces.5

Lee remained ill through the end of the war. He was diagnosed with heart disease, and during his remaining years, was plagued by “bouts of rheumatism.” One evening, while saying grace before dinner, he became aphasic, collapsed and died suddenly, presumably due to a fatal embolus launched from a heart valve damaged by rheumatic fever.

In the Trenches

Despite the heightened frequency of reactive arthritis among troops, the entity was not formally described until WWI. Contrary to popular belief, it was not the disgraced war criminal Hans Reiter, MD, who first reported this syndrome. Instead, we should bestow the honor on two French clinicians, Noel Fiessinger, MD, and Emile Leroy, MD, who described an “oculo-urethral-synovial” syndrome that occasionally developed post dysentery.6 In contrast, Reiter’s description, published several weeks following the French report, was rather brief. A mere two pages, it described a single case of urethral and joint symptoms in an army officer who subsequently developed ocular complaints.7 Most troublesome, however, was Reiter’s erroneous attribution of this illness to a spirochete infection. Until his death in 1969 at the age of 88, Reiter went to great lengths to promote his name and its use to designate the combination of urethral, joint and ocular symptoms.8

The brutality of warfare provided ample opportunity for clinicians to correlate the many traumatic peripheral nerve injuries with specific clinical disorders. These studies were pioneered during the Civil War by the Philadelphia physician, Silas Weir Mitchell, MD. He described the first cases of what he referred to as causalgia and what is now better known as complex regional pain syndrome. During WWI, enormous strides were made in understanding the function of the peripheral nervous system, led by neurologists whose names we recognize: the German, Paul Hoffman, MD, and the Frenchman, Jules Tinel, MD.

Not all neurologic insights were gained through the study of war injuries. Two other French clinicians, Georges Guillain, MD, and Jean-Alexandre Barré, MD, described a few unusual cases of paresthesias, progressive weakness and gait difficulties in French soldiers who had been admitted to a military hospital.9 They accurately distinguished this condition from the more common form of paralysis during that era, poliomyelitis, and believed that it carried a highly favorable prognosis. Curiously, a short time later, the eminent American neurosurgeon, Harvey Cushing, MD, who served with the American Expeditionary Force in France, was briefly stricken with Guillain-Barré syndrome himself. Cushing observed:9

Something has happened to my hind legs and I wobble like a tabetic and can’t feel the floor when I unsteadily get up in the morning.

Fortunately for Cushing and the world of medicine, he eventually fully recovered from this illness.

Life in the trenches was a miserable experience. Many, if not most, infantrymen suffered from low back pain or sciatica, whose relationship to disk impingement was unknown at the time. Some soldiers developed camptocormia, a bizarre posture characterized by an abnormal, severe and involuntary forward flexion of the thoracolumbar spine that became manifest during standing and walking and subsided in the recumbent position.8 Originally described as a psychogenic disorder or a form of malingering that was being used by some troops as a way to avoid military duty, it was later determined that these postures helped relieve their pain. Sadly, this insight may have come too late to save the lives of some soldiers who were court martialed and executed for dereliction of duty.

Through the ages, physicians have been at the warrior’s side, offering rudimentary forms of first aid medicine.

The Gas Attacks

In the Battle of Ypres, troops faced another unexpected lethal challenge—mustard gas. Released by the Germans to decimate their enemy, the use of poison gases significantly altered the dynamics of WWI, and all future wars. It also changed the course of medicine.

Early research studying the effects of mustard gas observed that it “attacked” leukocytes, but the major discoveries related to its potential medical uses came decades later during WWII. In 1943, an American cargo ship, the SS John Harvey, docked in the port of Bari, Italy, was attacked in an air raid and sank, along with its secret cargo of mustard gas bombs. More than a thousand people were exposed to the gas and nearly 80 died. Autopsies on the victims noted a consistent finding: profound bone marrow suppression. This information was passed along to two American pharmacologists, Louis Goodman, MD, and Alfred Gilman, MD, who were working for the U.S. Department of Defense exploring potential therapeutic applications of chemical warfare agents.

Drs. Goodman and Gilman had already converted the volatile mustard gas into the more stable nitrogen mustard by substituting a nitrogen molecule for sulfur. Based on the information provided to them, they surmised that nitrogen mustard might be useful in the treatment of lymphoma. Within months, this agent was given to the first cancer patient, whose tumor temporarily shrank. This seminal event marked the discovery of chemotherapy and immune suppression as viable cancer therapies.10 It was not long before our rheumatology forebears began administering cyclophosphamide, 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate to their sick patients.

Where the Poppies Grow

As a medical student, I used to walk by a beautiful stained-glass window honoring Lt. Colonel John MacRae, MD. A pathologist by training, he volunteered for military service in WWI at age 42. Devoted to his troops, he remained on duty even after his tour was completed. He is best remembered for writing the most memorable poem of the Great War, the haunting, “In Flanders Fields.” Written during the Battle of Ypres, it is an unforgettable account of war and bloodshed, death and destruction. And one of hope and humanity.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead.

Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields11

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Carter R. John McCrae (1872–1918): Doctor-Soldier-Poet. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997 Jan.;63(1):264–268.

- Gilbert M. The First World War: A complete history. New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1994:97–98, 447, 478, 508 and 133.

- Laffin J. Surgeons in the Field. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1970:224.

- Rodway GW. The foundations of wilderness medicine: Some historical features. Wilderness Environ Med. 2012 Jun.;23(2):165–169.

- Bollet AJ. Rheumatic diseases among Civil War troops. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Sep.;34(9):1197–1203.

- Fiessinger N, Leroy E. Contributions a l’etude d’une epidemie de dysenterie bacillaire dans la Somme. Bull Mem Soc Med Hop Paris. 1916;40:2030–2069.

- Reiter H. Über eine bisher unbekannte Spirochä- teninfektion (Spirochaetosis arthritica). Dtsche Med Wschr. 1916;42:1535–1536.

- Kahn M-F. The World War I (1914–1918) and rheumatology. Joint Bone Spine. 2014 Jul. 19:pii: S1297-319X(14)00157-2.

- Lanska DJ. Historical perspective: Neurological advances from studies of war injuries and illnesses. Ann Neurol. 2009 Oct.;66(4):444–459.

- Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies. Scribner & Sons. New York, 2010.

- McCrae J, Macphail A. In Flanders fields. Google e-book. http://books.google.com/books?id=Hgk1AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Author’s note: In my editorial, “Working Feverishly” (The Rheumatologist, September 2014), I should have credited the seminal research of Daniel Kastner, MD, PhD, senior investigator, Metabolic, Cardiovascular and Inflammatory Disease Genomics Branch, and head, Inflammatory Disease Section, whose numerous scientific contributions established the field of autoinflammatory disease, a term he coined.