Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil; HCQ) has been an important and effective drug for the treatment of lupus erythematosus and related autoimmune and inflammatory diseases for half a century, although its potential to cause retinal damage continues to raise concern among rheumatologists and ophthalmologists. Further, despite the overall safety profile of HCQ, some patients with preexisting vision problems (e.g., glaucoma, cataracts) may be reluctant to take a medication with any potential for ocular toxicity, thus depriving them of a valuable therapy.

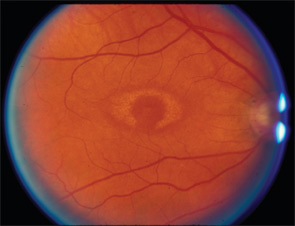

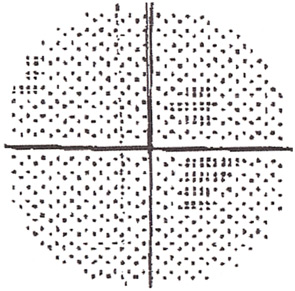

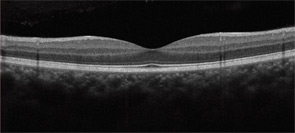

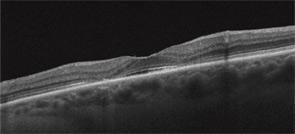

It is important to know the facts. Retinal complications from HCQ are actually rare (at proper dosage) and, with good screening, the risk for visual loss is very low. Nevertheless, retinopathy begins to appear with long-term use, and retinopathy is serious insofar as there is no known treatment. It can progress for a year or more after stopping the drug and, if not recognized early (at the point of screening), it can lead to functional blindness. The classic clinical picture of HCQ toxicity is a “bull’s eye” maculopathy (see Figure 1)—but as I’ll later note, this is a late finding.

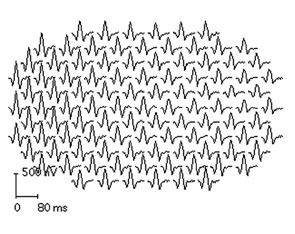

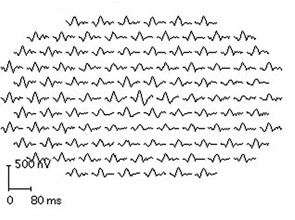

Data on retinal complications associated with HCQ and recommendations for screening for HCQ toxicity from the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) have been published recently, and they have important clinical and legal implications for the rheumatologist.1,2 This article is intended to highlight new knowledge about how this toxic effect develops and can be recognized.

TABLE 1: Ideal Weight

Women: 100 lb + 5 lbs per inch over 5 ft

Men: 110 lb + 5 lbs per inch over 5 ft

Incidence

The best data on HCQ toxicity are from the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.1 They suggest that, in an unselected population, the risk is below 1% for toxicity within the first five to seven years of treatment as long as dosage is within general guidelines. However, frequency of toxicity rises thereafter, probably reaching several percentage points by 15 to 20 years of use, although there were not enough cases in the data bank to give a firm number. From anecdotal data and the large number of overdose cases among published reports of toxicity, the risk is clearly accelerated and higher with overdose. Further, the recognition of toxicity may rise with the use of more sensitive diagnostic tools for screening. I have seen a dozen cases of toxicity in the past year, which is rather high for a suburban area, even when considering referral patterns.

Daily Dose

The new AAO recommendations focus more on the duration of treatment rather than a daily dose but emphasize that overdosage is dangerous.2 Most patients receive two tablets (400 mg) per day, which is fine for women taller than 5 ft. 7 in. or men taller than 5 ft. 5 in. Why is height important? Because the drug does not distribute in fatty tissues, so an “ideal” weight is a critical parameter for dose calculation. Many of the overdose cases I have seen have received dosage by weight, and these patients were overweight. The ideal weight formula is show in Table 1.