SAN FRANCISCO—Presentations from three leading experts in hematology during the ACR/ARHP 2008 Annual Meeting’s symposium, “Controversies in Prevention and Management of Hypercoagulable States in Rheumatic Disease Patients” revealed a common theme. Despite continual development of newer antithrombotic and antiplatelet agents, the successful management of patients in these complex clinical settings is best based—for now—on a combination of empiric wisdom and current clinical data, evolving practice guidelines, effective communication with colleagues (especially orthopedic surgeons), and thorough patient education.

A Balancing Act

The ideal antithrombotic, suggested Thomas L. Ortel, MD, PhD, director of the Anticoagulation Management Service and director of the Duke Clinical Coagulation and Platelet Immunology Laboratories at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., would be a targeted therapy with a rapid onset that requires very little monitoring. The agent’s action would also be reversible and would allow for a patient-specific regimen. But, he concluded, medicine is not there yet.

Newer antiplatelet drugs with a rapid onset, such as cangrelor, are more effective than clopidogrel in the cardiac cath lab setting. But with certain parenteral glycoprotein 2B-3A blockers, such as abciximab, patients can develop severe thrombocytopenia with bleeding. “Prasugrel is a case in point,” Dr. Ortel noted. “If you develop your anticoagulant too well, you arrive at a point of increasing complication rates.” The 13,000-patient TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, which compared prasugrel to clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes, showed significantly reduced rates of ischemic events but an increased risk of major bleeding with prasugrel.1 Fondaparinux, a synthetic pentasaccharide, has a predictable anticoagulant effect with once-a-day dosing and is effective for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, although it, too, is not easily reversible—a definite drawback if a patient requires urgent surgical intervention.

For ongoing anticoagulation therapy, clinicians will continue to face what Dr. Ortel characterized as “the shortcomings of warfarin therapy.” Because warfarin has such a narrow therapeutic index, the best methods to predict initial dosing and monitor therapy continue to elude researchers and clinicians. Despite recent buzz about polymorphism genotyping, there are no prospective data confirming its utility, said Dr. Ortel. Ordering the test for cytochrome P450 269 (CYP2C9) and vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR C1) increases costs (the test costs $200) and introduces a delay of two to three days for results. Some guidance can be obtained at www.warfarindosing.org, a free Web site launched by Brian Gage, MD, that allows the clinician to enter patients’ baseline coagulant response time (INRs), other comorbidities, and their CYP2C9 and VKOR C1 genotypes to obtain a recommended warfarin dose. The Web site is designed for initiation of warfarin therapy, and the time lag to obtain lab tests may mean that the patient is already on Day 3 or Day 4 of warfarin therapy.

To manage ongoing warfarin therapy, patient self-testing—when the patient performs the INR at home but contacts the healthcare provider for dose adjustment—and self-monitoring—when patients are taught to adjust their own warfarin—are used increasingly in the outpatient setting. Although patient involvement may have the potential to hit the therapeutic range, and studies have shown that time in therapeutic range goes up the more frequently you test the INR, Dr. Ortel has concerns about the medicolegal implications of this monitoring method.

Weighing the Guidance

Stephan Moll, MD, associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology/Oncology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, personalized his advice to the meeting participants regarding deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis. “If I was medically sick in your hospital or had hip or knee replacement, I would want to receive either low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH] or fondaparinux. I would not want just aspirin,” he asserted. This strategy is in alignment with the American College of Chest Physicians’ (ACCP’s) June 2008 clinical practice guidelines for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy.2 Dr. Moll culled information from the ACCP and other clinical practice guidelines and quizzed his audience with clinical scenarios to explicate DVT/pulmonary embolism (PE) prophylaxis as well as the management of venous and arterial thromboembolic risks.

Dr. Moll presented numerous scenarios in which rheumatologists may typically face decisions about effective DVT prophylaxis, an issue that is currently being targeted with recent initiatives promulgated by the Joint Commission for the Accreditation for Health Care Organizations, the U.S. Surgeon General, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ reimbursement rules. After total hip or knee replacement, the ACCP guideline advises use of LMWH, fondaparinux, or warfarin with a target INR of 2 to 3 for at least 10 days and as long as five weeks after the surgery.

Dr. Moll cautioned his audience to be aware of discrepant opinions between different specialties. For instance, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons would add aspirin to ACCP’s list of prophylactic strategies for postoperative DVT prophylaxis. “Unfortunately, patients are caught in between two different opinions,” he pointed out. “The surgeons don’t want the patients to bleed; the internal medicine folks don’t want the patients to clot.”

Rheumatologists should communicate with orthopedic surgeons at their institutions about their recommendations and try to achieve consensus about what the patient should get after surgery, Dr. Moll said. He recommends that patients with hypercoagulable states be treated with LMWH, fondaparinux, or warfarin.

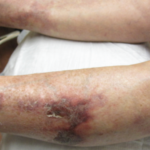

Dr. Moll also suggested strategies to stratify the risk for the recurrence of DVT or PE. ACCP guidelines recommend three months of anticoagulation for patients who have experienced DVT or PE associated with transient risk factors, such as surgery or major trauma. Patients with unprovoked DVT or PE should receive at least three months of anticoagulation. Those with unprovoked DVT or PE and a strong thrombophilia, such as antiphospholipid antibody (APLA) syndrome, double heterozygosity for factor V Leiden, and the prothrombin 20210 mutation protein C or protein S deficiency, or homozygosity for factor V Leiden, may fall into a higher risk group and may need to be treated with long-term anticoagulation therapy.

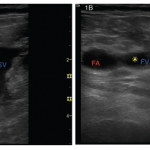

To ascertain the proper length of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, Dr. Moll would obtain a D-dimer (positivity predicts a higher risk for recurrence; a negative result places the person in the lower risk category) three to six months after the acute DVT or PE and a Doppler ultrasound of the legs (residual thrombus may be a predictor for recurrence). Additionally, Dr. Moll would factor in gender (males have higher risk for recurrence than females), type of thromboembolic event (PEs are more often fatal than DVTs), whether INRs have been stable, any episodes of bleeding, and lifestyle changes. Finally, he includes patient preferences to propose treatment plans and reevaluates the patient’s situation every six to 12 months.

As Dr. Moll and the other panelists noted, thrombosis can occur even with thrombocytopenia. Balancing anticoagulation therapy becomes especially tricky for patients who have APLA syndrome and inflammatory disease. As did Dr. Ortel, Dr. Moll advised the audience that the INR in patients with APLA syndrome can be unreliable and should be correlated with Factor II activity or chromogenic factor X to generate a treatment plan. Learn whether your anticoagulation clinic uses phlebotomy or point-of-care INR testing, he recommended.

Dr. Moll wrapped up his session by touching on the use of contraceptives, specifically the thrombosis risk associated with third-generation pills being greater than that with second-generation pills; vaginal bleeding, for which progestins or endometrial ablative procedures may be helpful; and vitamin K supplementation (100–150 mcg a day) to help stabilize fluctuating INRs. He also recommended two Web sites as good patient-education supplementation: www.stoptheclot.org and www.fvleiden.org.

Treatment Is Empiric

John G. Kelton, MD, a hematologist and dean of the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, concluded the symposium with an overview of microangiopathic anemias, especially thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). TTP is still a poorly understood disorder, he noted. Treatment continues to be empiric, based on findings first reported by Rubinstein in 1959 that plasma exchange produced unexpected remission from TTP—an illness that, untreated, has a mortality rate of 90%.3 Dr. Kelton and his colleagues in the Canadian Apheresis Study Group conducted a study 18 years ago of patients with TTP, some of whom had lupus and other autoimmune markers.4 Their study compared plasma infusion with plasma exchange, demonstrating a significant benefit of the latter, which continues to be a mainstay of treatment for these patients. At his institution, clinicians do not use the ADAM TS-13 test as a measure of disease activity. The test, said Dr. Kelton, cannot inform a clinician about altering, stopping, or continuing therapy.

Epidemic HUS TTP is becoming increasingly prevalent in Canada, Dr. Kelton reported, because of the increase in the use of organic foods by the general population. Caused by E. coli H-0157, classic HUS TTP will affect about 2% to 3% of the exposed population and can cause long-lasting renal impairment in children. It is more likely to be fatal in adults. Again, small nonrandomized studies also seem to suggest that plasma exchange works in these patients. Although treatment of thrombotic microangiopathies remains “remarkably arbitrary”—even in late 2008—the treatment works, he observed.

References

- Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001-2015.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S-453S.

- Rubinstein MA, Kagan BM, Macgillviray MH, Merliss R, Sacks H. Unusual remission in a case of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura syndrome following fresh blood exchange transfusions. Ann Intern Med. 1959;51:1409-1419.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:393-397.