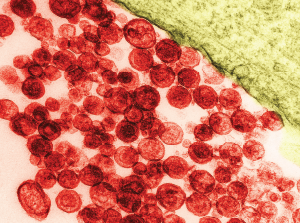

Particles of human T-lymphotropic virus 1 on a transmission electron micrograph. The virus has been implicated in lymphoma development.

David M. Phillips / Science Source

A 57-year-old Ghanaian woman was referred to our rheumatology practice with acute, left elbow swelling and pain. The referring oncologist suspected gout, because the patient had hyperuricemia.

Six months before, the patient was diagnosed with stage IV human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-associated adult T cell lymphoma (ATLL). Her initial oncologic manifestations included multiple thoracic, abdominal and retroperitoneal masses. Biopsy of an abdominal mass showed histological and immunohistochemical features of T cell lymphoma with CD3 positivity. Serologic assay and Western blot were positive for HTLV-1. The patient had osteoblastic lesions of the skull, and axial and appendicular skeleton, including bilateral distal humerus diaphyses. She developed a pathologic fracture of the right mid-humerus that was treated conservatively.

Chemotherapy was started with CHOP and methotrexate.

The patient initially had significant clinical and radiologic improvement in the right humerus fracture, abdominal masses and lymphadenopathy. However, at the end of the treatment, she developed right facial numbness, with radiographic evidence of progression in the calvarium, and was started on whole brain radiation therapy. She was a poor candidate for more aggressive chemotherapy, because she was a Jehovah’s Witness and declined blood products. At this time, the patient also reported new, left elbow pain and was referred to the rheumatology clinic.

Rheumatology Workup

At the initial rheumatology evaluation, the patient described one month of worsening left elbow pain, without any other associated symptoms. The exam was significant for a warm and swollen left elbow with limited extension. Her other joints were not swollen or tender. She had no palpable tophi.

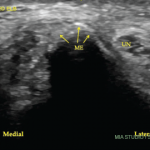

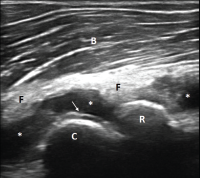

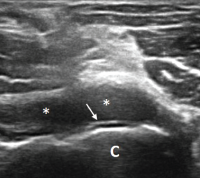

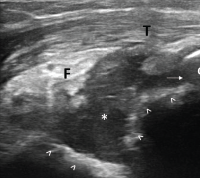

Her uric acid level was 12.7 mg/dL. An X-ray of the left elbow did not show fracture or lytic lesions. Ultrasound demonstrated a large, partially compressible, anechoic to hypoechoic Doppler-negative collection in the left elbow joint, anteriorly and posteriorly (see Figure 1, & Figures 2 & 3). On longitudinal anterior humero-radial view, a continuous hyperechoic line was present over the hyaline cartilage of the humeral capitellum, which raised suspicion for a double contour (DC) sign (see Figure 1). On anterior transverse view, this linear band was also visible, but was more suggestive of an interface sign (see Figure 2).

Joint aspiration revealed hazy serous fluid, with 1,200 red blood cells, 3,900 white blood cells (21% leukocytes, 6% lymphocytes and 73% monocytes) and no crystals. On cytology, a large number of abnormal lymphocytes were seen, compatible with malignant effusion from the patient’s lymphoma. A repeated joint aspiration for additional synovial fluid for immunofluorescence and flow cytometry was planned, but unfortunately, two days later, the patient acutely decompensated, transitioned to comfort care and declined further procedures.

Figure 1. Ultrasound of the left elbow: anterior humero-radial longitudinal view. A large anechoic to hypoechoic collection (*) is present in the anterior elbow joint, which superiorly displaces the fatpad (F) and the brachialis muscle (B). This collection extends proximal to the humeral capitellum (C) into the radial fossa (left sided *) and distal to the radial head (R) to the annual recess (right sided *). There is a hyperechoic linear band (arrow) over the superficial margin of the hyaline cartilage of the humeral capitellum.

Figure 2. Ultrasound of the left elbow: anterior transverse view of the radial aspect of the joint. A large anechoic collection (*) is present in the anterior radial joint space. There is a hyperechoic linear band (arrow) over the superficial margin of the hyaline cartilage of the humeral capitellum (C).

Figure 3. Ultrasound of the left elbow: posterior longitudinal view. There is a large, anechoic to hypoechoic collection deep to the triceps muscle (T) in the olecranon fossa (*) and posterior elbow joint recess (arrow), which superiorly displaces the posterior fatpad (F). For landmarks, note the olecranon process (O), the humeral trochlea (arrows).

Diagnostic Pearls

In this patient’s multidisciplinary evaluation, we bring up two diagnostic pearls.

First, the abnormal lymphocytes aspirated from the patient’s elbow joint suggest synovial infiltration by lymphomatous cells. This is a very rare complication of lymphoma/leukemia, but should be considered in patients with adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) with acute joint effusion.

A prior case features a patient with HTLV-1 infection and ATLL who developed polyarthritis and malignant synovial infiltration, and responded to radiation, steroids and targeted immunomodulatory therapy.1

A handful of other cases of HTLV-1-associated ATLL with lymphomatous synovial infiltration have also been described.2-4 In these cases, synovial fluid cytology and flow cytometry confirmed presence of malignant cells with CD3, CD4 and T cell receptor profiles consistent with those in the peripheral blood, lymph node biopsies and other systemic sites.3,4 Unfortunately, our patient developed intractable disease and moved to hospice prior to full diagnostic confirmation of synovial fluid flow cytometry.

Second, we would like to focus on the sonographic double contour sign, which is created by deposition of uric acid crystals on the surface of the hyaline cartilage. The DC sign is defined by OMERACT as a hyperechoic band over the superficial margin of the articular hyaline cartilage that can be continuous or intermittent, regular or irregular and is independent of the angle of insonation (the angle of the ultrasound beam).5

This may be difficult to distinguish from the cartilage interface sign, which is an artifact. Cartilage interface sign is a thin, markedly hyperechoic line at the interface between the normal hyaline cartilage and an overlying abnormally hypoechoic or anechoic material, which is caused by a marked difference in acoustic impedances of the two tissues (e.g., effusion and hyaline cartilage).6

The diagnosis of malignant effusion should be considered in patients with HTLV-1-associated ATLL who present with joint swelling.

Our patient had ultrasound findings of a possible DC sign on anterior humero-radial longitudinal view. When this image alone was presented to a handful of ultrasound experts, five out of seven thought this represented a DC sign. The other two felt this was a cartilage interface sign. An OMERACT patient-based agreement and reliability exercise on lesions in gout found that intra- and interobserver reliability for DC was lower than for other elementary lesions of gout (tophus, erosions). The authors thought that one possible pitfall was the presence of cartilage interface sign in joints with effusion (for example in the knees).5

Dynamic imaging can help differentiate DC from cartilage interface sign. The cartilage interface sign should be present only when the insonation angle is 90º (when the ultrasound beam is perpendicular to the surface of the cartilage). The DC sign should also be present in areas where the insonation angle is <90º and should move with the cartilage during dynamic imaging because the crystals are deposited on the surface of the cartilage.

Another helpful maneuver is compression with the probe. If the effusion is compressed out of view, the cartilage interface sign should disappear, while the DC sign should remain.6

Finally, the presence of other elementary lesions of gout (erosion, tophus) increases the positive and negative predictive value for the correct diagnosis.7

One should also note that the DC sign has been described not only in patients with gout, but also in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia and that the presence of the DC sign correlates with the degree of hyperuricemia.8,9 However, to date no study has looked at synovial fluid from joints with DC sign from patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia for the presence of uric acid crystals.

Conclusion

In summary, we present a rare case of suspected malignant synovitis in a patient six months after diagnosis of HTLV-1-associated ATLL. Most prior case reports describe malignant polyarthritis developing several years after initial ATLL diagnosis, rendering our patient’s accelerated clinical course potentially a unique presentation even within a rare condition. This may be confounded by a delay in workup in our patient; she only had one year of documented care in our system despite living locally for 12 years before then.

This case highlights that the diagnosis of malignant effusion should be considered in patients with HTLV-1-associated ATLL who present with joint swelling and that synovial fluid cytology and flow cytometry should be requested.

Ultrasound is an emerging imaging tool in rheumatology practice that provides valuable information beyond the physical exam. In patients with joint effusions, differentiating DC sign from cartilage interface sign can be difficult. One should obtain synovial fluid for a definitive diagnosis of gout even when the clinical suspicion is high.

Veronika Sharp, MD, is a faculty rheumatologist at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (SCVMC) in San Jose, Calif., and an affiliated clinical associate professor at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. She is director of musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasonography in rheumatology at SCVMC.

Veronika Sharp, MD, is a faculty rheumatologist at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (SCVMC) in San Jose, Calif., and an affiliated clinical associate professor at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. She is director of musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasonography in rheumatology at SCVMC.

Alice Chuang, MD, is an internal medicine resident at SCVMC.

Alice Chuang, MD, is an internal medicine resident at SCVMC.

Lily Kao, MD, RMSK, is a rheumatologist in San Jose, Calif., and is a volunteer faculty member at SCVMC in MSK ultrasonography.

Lily Kao, MD, RMSK, is a rheumatologist in San Jose, Calif., and is a volunteer faculty member at SCVMC in MSK ultrasonography.

Midori Jane Nishio, MD, RhMSUS, is a rheumatologist in Walnut Creek, Calif., and a volunteer faculty member at SCVMC and Stanford University in MSK ultrasonography.

Midori Jane Nishio, MD, RhMSUS, is a rheumatologist in Walnut Creek, Calif., and a volunteer faculty member at SCVMC and Stanford University in MSK ultrasonography.

References

- Koster MJ, McPhail ED, Chowdhary VR. Synovial infiltration in human T lymphotropic virus type I-associated T cell leukemia/lymphoma. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Apr;67(4):945.

- Tachibana J, Shimizu S, Takiguchi T, et al. Lymphomatous polyarthritis in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993 Nov;11(5–6):459–467.

- Dennis G, Chitkara P. A case of human T lymphotropic virus type I-associated synovial swelling. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007 Nov;3(11):675–680.

- Yancey WB Jr., Dolson LH, Oblon D, et al. HTLV-I-associated adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma presenting with nodular synovial masses. Am J Med. 1990 Nov;89(5):676–683.

- Terslev L, Gutierrez M, Christensen R, et al. Assessing elementary lesions in gout by ultrasound: Results of an OMERACT patient-based agreement and reliability exercise. J Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;44(1):130.

- YE Miedany. (2015) Musculoskeletal Ultrasonography in Rheumatic Diseases. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Ogdie A, Taylor WJ, Neogi T, et al. Performance of ultrasound in the diagnosis of gout in a multicenter study comparison with monosodium urate monohydrate crystal analysis as the gold standard. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb;69(2):429–438.

- Reuss-Borst MA, Pape CA, Tausche AK. Hidden gout—Ultrasound findings in patients with musculo-skeletal problems and hyperuricemia. Springerplus. 2014 Oct;9;3:592.

- Thiele RG, Schlesinger N. Ultrasonography shows disappearance of monosodium urate crystal deposition on hyaline cartilage after sustained normouricemia is achieved. Rheumatol Int. 2010 Feb;30(4):495–503.