Innovative Immunology

Outside the clinic, whenever I crack open a journal, such as Arthritis Care & Research, I am thrilled to see that our field is advancing at a frenetic pace. In only the past few years and decades, we have come to appreciate entirely new subsets of immune cells, receptors and cytokines. From innate lymphoid cells to anti-cytokine antibodies to elaborate neutrophil extravasation traps, it’s astounding how much more expansive our immune systems are, beyond our wildest imaginations. The description of the immune system, dryly taught to us as a machine with gears and cogs, seems insulting to its majesty. With every discovery, the immune system seems much more like a magical forest brimming with hidden and imaginary creatures.

This is more than just idle philosophical musing. When the fellows and I reason through a complex case by thinking about the immunological basis of disease, it fills me with a great sense of humility. We may tell ourselves elaborate stories about how neutrophils are activated or how T cells are polarized, but these beliefs are likely fictional. Within the human form is likely an infinitesimally deep series of connections between cells and proteins and other constituents that our brains cannot comprehend.

The fact that our medications work as they are intended to is a bit of miracle in and of itself. After all, we’re tampering with unseen forces, and yet, for the most part, we end up with our desired results.

The Clinical State of the Art

A few years ago, at an ACR annual meeting, I was enlightened to hear about how methotrexate is an inhibitor of Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription ( JAK/STAT) signaling and how that mechanism of action is perhaps more relevant than what has been written about methyltetrahydrofolate reductase inhibition. It seems to make so much more sense, yet we still drill into young trainees a likely peripheral mechanism of action rather than diving into the fascinating cutting edge. Why?

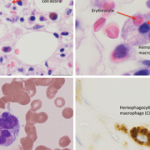

On the other end of the spectrum, we continue to overturn clinical adages and practices that we learned from our forbears. Before the pandemic, the concept of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was somewhat controversial. It hovered halfway between mythical creature and diagnostic folly (when it wasn’t primary HLH/macrophage activation syndrome [MAS] in kids). I remember as a resident rotating in the medical intensive care unit, being scolded by hematologists not to waste their time and resources on consults for HLH/MAS.