A Roshi (i.e., master) apparently said that in Zen, “there is nothing to believe and everything to discover.” Interestingly enough, I have never been able to confirm who actually said that, which makes this saying about belief and discovery particularly apt. Regardless, I think about those words at least twice a day when I am in the clinic because even though I may not be a Zen master, I am a rheumatologist.

A Roshi (i.e., master) apparently said that in Zen, “there is nothing to believe and everything to discover.” Interestingly enough, I have never been able to confirm who actually said that, which makes this saying about belief and discovery particularly apt. Regardless, I think about those words at least twice a day when I am in the clinic because even though I may not be a Zen master, I am a rheumatologist.

What I love about the saying is its two parts and their connection to one another. It embraces both a skepticism and a curiosity that doesn’t seem nihilistic or contrived. It strikes the perfect balance—one that seems to define our field. In fact, in this day and age, I think it should be a mantra for us. New cells, new therapies and new insights into disease and illness are revolutionizing what it even means to be a rheumatologist. Almost nothing seems to be off limits. Long-held orthodoxies are routinely questioned by enterprising heretics and iconoclasts. Other times, accidental developments drive insights into disease and treatment. We’re privileged to live in an amazing revolutionary age.

Everyday Clinical Discovery

The most exciting discoveries that I engage in as a clinical rheumatologist are the relatively boring, everyday things that I learn about my patients. No matter how long I have known them or how simple their case is, I always find something new about them—a hobby, a relation, a local claim to fame, an accomplishment, and so forth. I’ve discovered much about the ins and outs of corn and soy agriculture through my encounters with farmers, and about the varied geography of Iowa’s quirky micropolises.

Beyond those, my favorite encounters are those that challenge my own beliefs about who people are and what constitutes human nature. One time I had a patient with a thick rural Appalachian accent and a dirty trucker cap smelling of tobacco. I had no idea that he had a PhD in Sanskrit studies and was a noted scholar in his day. He even enlightened me on the subtle meaning behind my very own name. Another time, I encountered a veteran who regaled me with stories of being in Washington, D.C., and entertaining the Roosevelt family. I would have never suspected, and perhaps never have believed, this story unless I heard it firsthand.

Such encounters, which are commonplace in rheumatology, can only happen when there’s a sense of humility and respect on both sides of the patient and clinician therapeutic alliance. The joy of rheumatology, perhaps uniquely among the different fields of medicine, comes from seeing patients in relationships that evolve over time. I am always in awe that there is so much more to discover. I’d like to believe that patients enjoy discovering the various things that are happening in our lives, too.

Innovative Immunology

Outside the clinic, whenever I crack open a journal, such as Arthritis Care & Research, I am thrilled to see that our field is advancing at a frenetic pace. In only the past few years and decades, we have come to appreciate entirely new subsets of immune cells, receptors and cytokines. From innate lymphoid cells to anti-cytokine antibodies to elaborate neutrophil extravasation traps, it’s astounding how much more expansive our immune systems are, beyond our wildest imaginations. The description of the immune system, dryly taught to us as a machine with gears and cogs, seems insulting to its majesty. With every discovery, the immune system seems much more like a magical forest brimming with hidden and imaginary creatures.

This is more than just idle philosophical musing. When the fellows and I reason through a complex case by thinking about the immunological basis of disease, it fills me with a great sense of humility. We may tell ourselves elaborate stories about how neutrophils are activated or how T cells are polarized, but these beliefs are likely fictional. Within the human form is likely an infinitesimally deep series of connections between cells and proteins and other constituents that our brains cannot comprehend.

The fact that our medications work as they are intended to is a bit of miracle in and of itself. After all, we’re tampering with unseen forces, and yet, for the most part, we end up with our desired results.

The Clinical State of the Art

A few years ago, at an ACR annual meeting, I was enlightened to hear about how methotrexate is an inhibitor of Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription ( JAK/STAT) signaling and how that mechanism of action is perhaps more relevant than what has been written about methyltetrahydrofolate reductase inhibition. It seems to make so much more sense, yet we still drill into young trainees a likely peripheral mechanism of action rather than diving into the fascinating cutting edge. Why?

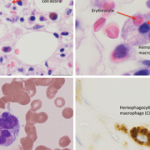

On the other end of the spectrum, we continue to overturn clinical adages and practices that we learned from our forbears. Before the pandemic, the concept of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was somewhat controversial. It hovered halfway between mythical creature and diagnostic folly (when it wasn’t primary HLH/macrophage activation syndrome [MAS] in kids). I remember as a resident rotating in the medical intensive care unit, being scolded by hematologists not to waste their time and resources on consults for HLH/MAS.

Now, HLH is very much in the realm of reality, although just as mysterious as it was before. The COVID-19 pandemic brought HLH out of the shadows and re-presented it as cytokine storm. While immunomodulator use in COVID-19 infection remains controversial, most folks acknowledge that there’s a role that immune dysregulation plays in the severity of infection.

And, as we move further away (we hope) from the height of the pandemic, we’re beginning to realize that viral-induced cytokine storms are commonplace. Well-regulated spikes in cytokines may be really important in clearing germs and restoring function. And when unregulated, cytokine storm can be the first sign of an underlying immune dysfunction.

Even osteoarthritis research is experiencing a resurgence. No longer just a disease of wear and tear, osteoarthritis—the most common form of arthritis—is now recognized as a complex condition mediated by inflammation, ischemia and other forces. It has upended even the most basic conversations between patients and clinicians about what arthritis is.

Among Learners & Teachers

Education is a particularly interesting case in which this adage seems to come to the fore. Education is supposed to impart a sense of wonder and discovery in trainees, but is often riddled with preexisting beliefs. Luckily, intrepid clinician scholar educators are empirically proving or disproving firmaments of faith in education. For example, the old and persistent myth of learning styles has been disproved, time and time again. Previously, we believed that some people are visual learners and others are more auditory. It seemed to make sense and was a pillar of belief among educators at all levels.

And yet, trial after trial and experiment after experiment with learners of all ages showed that this paradigm wasn’t just false but also downright harmful to learners. We discovered that the belief about learning styles placed a lot of burden on teachers to tailor learning plans without much benefit. The myth of learning styles also prevented us from truly individualizing learning plans because we lumped people into categories that seemed to make sense, but didn’t actually exist.1

Discovery in Advocacy

Perhaps the most lovely discoveries are the ones in the hospital, or the clinic. “I didn’t know I could order that!” Or “What an amazing service he provides!” Is something I often exclaim despite being at my current workplace for nine years. When I talk to people from other hospitals, they don’t quite understand the excitement, but it doesn’t detract from my enthusiasm in the least because I imagine they also have their everyday institutional discoveries.

Or maybe not. To make such discoveries within large institutions requires an active and consistent engagement. It requires a curiosity about why things are the way they are and leadership among teams to foster criticism about long-held beliefs. It’s a type of magic in and of itself to see how a complex institution develops a life of its own.

This remains true at even larger scales. Legislative advocacy rests, in and of itself, on the supposition that with enough passion and skill anything can happen. Discovering where that passion and skill lie is the challenge. Indeed, advocacy, especially with the topics that rheumatologists care about, is all about discovering what aligns healthcare systems with the best quality of care that we can provide to patients. It requires questioning why things are the way that they are today—embracing both skepticism and an inquisitive mindset.

Effective DEI Efforts Require Discovery

On a similar note, discovery is also essential in our pursuit of social justice. So much of the world around us has been designed to conform to our prior held beliefs. Many of these beliefs, even those held by people who are otherwise well-meaning, are riddled with prejudice and bias. The strength of these beliefs is matched by the full-throated defense of them.

To move forward, we are obligated to critically rethink those assumptions until there is (next to) nothing to believe. We have to examine the totality of the environment in which we are immersed. We have to ask ourselves what we should retain and what we should discard. It’s not an easy task, but what I think deepens our commitment is an attitude that embraces curiosity and discovery.

More to the point, we should try to embrace this spirit of discovery without any preconceived notions about where our inquiry may lead us. It can be deeply discomforting to discover things that we may not have wanted to know, but it can be equally as liberating and empowering to delve into the gray areas.

With respect to rheumatology, this is especially important. Prior beliefs that are now recognized as myths, such as racial predispositions to certain diseases, have been revisited—to the great benefit of our patients. The textbook statement that polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis (PMR/GCA) was predominantly a disease of white people is a great example.2 Patients and clinicians alike have been vindicated; their observations were worthy of appraisal and further investigation.

Self-Discovery

Throughout all of these different facets of rheumatology, there may be a common theme that you may be noticing. I would like to believe that the Zen Buddhists would agree with me, but of course I cannot speak on their behalf. Discovery must start from within. We must look deep down within ourselves to find why we discover: What is that impulse that makes us seek to be better people and rheumatologists? What is the spark that ignites joy and discovery? Is this the secret to understanding why we thrive?

As much as I’d like to believe there is nothing to believe, that is clearly not true. We must remain true to our moral precepts and to the values of ethical and humanistic care. Contrarianism for the sake of being seen as a disbeliever isn’t particularly constructive. Therein lies the paradox.

If we are meant to be unbelievers, how do we ward off the omnipresent threat of becoming nihilists? How do we maintain confidence in ourselves when we have every reason to doubt what we believe and who we are? The short answer: I don’t know. But those are questions whose answers are always worth discovering, and rheuminating upon.

Bharat Kumar, MD, MME, FACP, FAAAAI, RhMSUS, is the associate program director of the rheumatology fellowship training program at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and the physician editor of The Rheumatologist. Follow him on Twitter @BharatKumarMD.

Bharat Kumar, MD, MME, FACP, FAAAAI, RhMSUS, is the associate program director of the rheumatology fellowship training program at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and the physician editor of The Rheumatologist. Follow him on Twitter @BharatKumarMD.

References

- Newton PM, Najabat-Lattif HF, Santiago G, Salvi A. The learning styles neuromyth is still thriving in medical education. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021 Aug 11;15:708540.

- Gruener AM, Poostchi A, Carey AR, et al. Association of giant cell arteritis with race. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019 Oct 1;137(10):1175–1179.