The Case

A 47-year-old woman presented with a one-year history of bilateral submandibular gland swelling, mild symptoms of xerostomia and xerophthalmia and arthralgias in her fingers. A review of systems was otherwise unremarkable.

On physical examination, her submandibular glands on both sides were enlarged and had a firm texture. Her parotid glands were normal, as were her cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes. The conjunctiva was normal, and the oral mucosa was moist. The rest of the exam was normal.

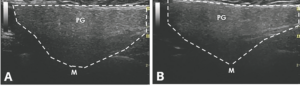

An ultrasound revealed hypoechoic nodules replacing large segments of both submandibular glands, with distortion of gland architecture, creating irregular gland surfaces and increased Doppler signal bilaterally. The parotid glands appeared normal (see Figures 1A–E).

Laboratory testing was significant for a positive anti-nuclear antibody test at 1:160 (speckled pattern), and elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibody at 4.2 (reference range [RR]: <1.0 is negative), anti-La/SSB antibody, rheumatoid factor, thyroid-stimulating hormone, creatinine kinase and serum IgG4 level were all within normal limits. Her C-reactive protein (CRP) was normal, but her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated at 47 mm/hr (RR: 0–15 mm/hr).

A chest X-ray revealed no hilar lymphadenopathy.

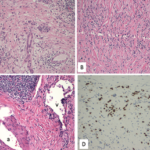

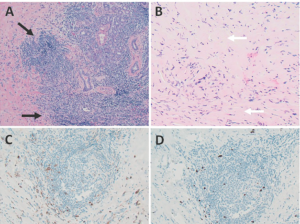

Biopsy of the right submandibular gland displayed florid intralobular storiform fibrosis, and chronic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with an IgG4 to IgG ratio of 1:4 and focally increased IgG4 plasma cells: 14 per high-powered field (see Figures 2A–D). Although obliterative phlebitis was not observed and the ratio of IgG4/IgG cells was not >40%, the overall histomorphological feature was suggestive of IgG4-related sialadenitis. The patient was started on prednisone, resulting in improvement of her submandibular swelling and arthralgias.

FIGURES 1 C, D & E: Left longitudinal submandibular gland with nodular hypoechoic lesions (C). Right longitudinal submandibular gland (D) with larger hypoechoic lesions producing a bulging on the surface of the gland. Large amount of Doppler signal within the right submandibular gland (E). Parotid gland (PG), submandibular gland (SMG), masseter muscle (M), mylohyoid muscle (MH) hyoglossus muscle, facial artery (A). The white arrows indicate areas of IgG4 involvement. The white dashed lines outline the glands. (Click to enlarge.)

Discussion

When a patient presents with submandibular gland swelling, xerostomia, xerophthalmia and positive anti-SSA antibody, Sjögren’s disease is usually at the top of the differential diagnosis. However, it is crucial to consider mimics of Sjögren’s disease, including IgG4-related disease (RD), lymphoma, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, HIV-related and non-inflammatory causes (e.g., diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, liver cirrhosis and bulimia).

This case demonstrates a potential role of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for evaluating salivary gland diseases. For sonographic evaluation of the salivary glands, it is important to examine both the parotid and submandibular glands, along with the thyroid gland. The parotid gland, positioned in the retromandibular fossa, exhibits an irregular wedge-shaped appearance. The submandibular gland, about half the size of the parotid gland, resides in the posterior aspect of the submandibular triangle, bordered by the body of the mandible, the anterior belly and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Their echotexture and homogeneity can be compared with the thyroid gland for reference.1

Various ultrasonographic scoring systems have been developed for primary Sjögren’s disease, assessing gland tissue characteristics, such as echogenicity, homogeneity, calcification, and lymph node and border clarity.2 DeVita et al. proposed a 0–4 grading scale based on hypoechoic areas, calcification and hyperechoic bands, offering a quicker and simpler approach to evaluating salivary glands.3

Ultrasound can increase sensitivity while preserving specificity for primary Sjögren’s disease beyond the 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria, ultimately improving overall accuracy.4 In primary Sjögren’s disease, the parotid gland is typically affected earlier than the submandibular gland. A characteristic ultrasound finding is the presence of multiple, small, oval, hypoechoic areas scattered throughout the gland, leading to an inhomogeneous appearance. These lesions resemble cysts, but lack posterior acoustic enhancement, suggesting they are dilated ducts or destroyed parenchyma filled with lymphocytic infiltrate. These lesions can also enlarge with disease progression and can exhibit increased parenchymal blood flow on color Doppler studies.1,5 However, these hypo/anechoic lesions can also be seen in amyloidosis and sarcoidosis, and there is no clear preference for parotid or submandibular gland involvement in these conditions.6

FIGURES 2 A, B, C & D: Right submandibular gland biopsy: (A) H&E staining with marked lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (black arrows) without evidence of obliterative phlebitis; (B) fibrosis (white arrows) arranged in a swirling pattern known as storiform fibrosis, which is a hallmark feature of IgG4-RD; immunohistochemistry showed focally increased IgG+ (brown cytoplasmic

staining); (C) IgG4+ (brown cytoplasmic staining); and (D) plasma cells with a ratio of ~4:1. The key histologic features of IgG4-RD are dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform-patterned fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis and infiltration of IgG4+ plasma cells with ratio of

IgG4/IgG cells >40%, and >10 IgG4+ plasma cells/high-powered field in biopsy tissue sample. (Click to enlarge.)

Ultrasonography findings in IgG4-RD and Sjögren’s disease show both similarities and differences. A reticular pattern can be observed in both conditions, but a distinct nodal pattern is more common in the submandibular glands of IgG4-RD and can help distinguish it from Sjögren’s disease.7 This nodal pattern is characterized by hypoechoic, focal, homogenous areas with increased vascularity and protrusion from the surface of the glands. Submandibular glands are predominantly affected in IgG4-RD, while the involvement of parotid glands is less frequent.6 The presence of focal, hypoechoic nodular lesions primarily affecting the submandibular glands while sparing the parotid glands may indicate IgG4-RD.

In contrast, conditions that mainly affect the parotid glands and less frequently the submandibular glands include diabetes mellitus, MALT lymphoma or benign lymphoepithelial lesions in HIV. In diabetes mellitus, the parotid glands can appear hyperechogenic due to fatty infiltration and their size may correlate with HgbA1C levels.1,8 In MALT lymphoma, the disease commonly affects the thyroid and salivary glands, especially the parotid glands. Sonographic findings include “linear echogenic strands pattern” or “multiple small hypoechoic nodules” (tortoiseshell/segmental pattern). In HIV-associated disease, parotid involvement is common, while submandibular glands are usually spared, appearing as larger but more focal cystic lesions with septation and producing through transmission.1,5

Conclusion

Ultrasonography is valuable for diagnosing salivary gland diseases, aiding in the differentiation of primary Sjögren’s disease. When submandibular gland involvement with focal, nodular hypoechoic lesions is present while sparing the parotid glands, IgG4-RD in the salivary glands should be considered.

Hung Vo, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Boston Medical Center.

Zhichun Lu, MD, is a pathologist at Boston Medical Center. She is an assistant professor at Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine at Boston University, in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

Eugene Kissin, MD, is a rheumatologist at Boston Medical Center. He is a clinical professor of medicine and the program director for the rheumatology fellowship program at Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine at Boston University.

References

- Kissin EY, Sharp V. Salivary Gland Ultrasound for Sjögren’s Syndrome. Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in Rheumatology Review. 2nd ed. Springer; 2021.

- Jousse-Joulin S, Gatineau F, Baldini C, et al. Weight of salivary gland ultrasonography compared to other items of the 2016 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Intern Med. 2020 Feb;287(2):180–188.

- De Vita S, Lorenzon G, Rossi G, et al. Salivary gland echography in primary and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992 Jul–Aug;10(4):351–356.

- Cornec D, Jousse-Joulin S, Pers JO, et al. Contribution of salivary gland ultrasonography to the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome: Toward new diagnostic criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):216–225.

- James-Goulbourne T, Murugesan V, Kissin EY, et al. Sonographic features of salivary glands in Sjögren’s syndrome and its mimics. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020 Jun 19;22(8):36.

- Law ST, Jafarzadeh SR, Govender P, et al. Comparison of ultrasound features of major salivary glands in sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Oct;72(10):1466–1473.

- Shimizu M, Okamura K, Kise Y, et al. Effectiveness of imaging modalities for screening IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis (Mikulicz’s disease) and for differentiating it from Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), with an emphasis on sonography. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015 Aug 23;17(1):223.

- Gupta A, Ramachandra VK, Khan M, et al. A cross-sectional study on ultrasonographic measurements of parotid glands in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Dent. 2021 Mar 2:2021:5583412.