The Case

An 18-year-old woman first presented with findings of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) including arthritis, fever, photosensitivity, hair loss, oral ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon, mild leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Antinuclear antibodies and anti-dsDNA were positive, but there was no evidence of nephritis. She was treated with low-dose glucocorticoids and hydroxychloroquine. A few months later, she developed lower-extremity edema, and her urinalysis showed an active urine sediment and proteinuria of 1 g/24 hr. She was treated with prednisone 60 mg/day for presumed proliferative lupus nephritis and is referred to you.

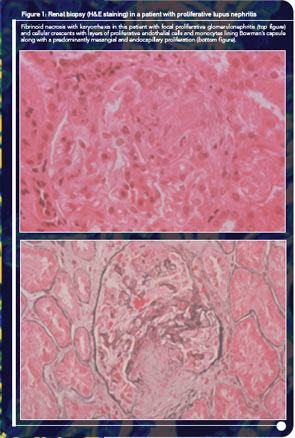

At the time of your evaluation, she is on prednisone 30 mg/day. Urinalysis showed an active sediment with proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hr. Laboratory values were significant for a hematocrit of 32%, serum creatinine of 1.0 mg/dl, urea 103 mg/dl, and albumin 3.4 mg/dl. Both C3 and C4 titers were low. A renal biopsy showed focal, segmental glomerulonephritis with an activity index of 8 and a chronicity index of 1. On renal biopsy, there were a few areas of fibrinoid necrosis and fibro-epithelial crescents in less than 10% of the renal glomeruli (see Figure 1).

How would you treat this patient? Would you use azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or cyclophosphamide (CY)? What is the evidence for your choice?

Although immunosuppressive agents are widely used for the treatment of severe manifestations of SLE, the choice of particular agents is a matter of considerable debate. Among all agents, CY was the first to demonstrate major successes in the treatment of severe disease, especially glomerulonephritis. In the past decade (2000–2010), however, the emergence of MMF for the treatment of nephritis has for some signaled the end of the “cyclophosphamide era.” Should MMF replace CY as the initial treatment of choice for severe disease? With the first biologic agent just recommended for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, have we entered the “era of biologic therapies” in lupus, with other traditional small molecule agents soon becoming obsolete?

The authors have followed closely the CY and MMF trials both in the United States and in Europe, and we have wrestled with the safety and efficacy issues regarding their use. In this article, we will review the existing data in an effort to provide answers to three fundamental questions regarding immunosuppressive therapy in lupus: Why, When, and How? More importantly, we will argue that the time has come to move our attention away from debating the merits of individual drugs. Rather, we believe that we should focus our efforts on developing a more comprehensive strategy to guide the treatment of lupus. This strategy should both “fit the patient” and achieve timely and long-lasting remission with the lowest possible harm.

Immunosuppressive Therapy in Lupus

Today most experts agree that the treatment of severe lupus involves a period of intensive immunosuppressive therapy aimed at halting immunological injury (induction therapy), followed by a period of less aggressive maintenance therapy to maintain the response. The latter period is essential to prevent flares and organ damage accrual. Although this strategy seems logical, it has not been formally tested against a “wait and treat the flare” approach.

Studies dating back to as far as the 1960s clearly demonstrated that high-dose glucocorticoids were not effective in halting end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in proliferative lupus nephritis (LN), with most patients requiring hemodialysis after five to 10 years. This observation, coupled with an increased awareness of steroid toxicity, provided the impetus in subsequent years to explore alternative immunosuppressive agents with an emphasis on AZA and CY. In these trials, most of the data originated from two centers in the United States: Mayo Clinic and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Azathioprine

Early studies by Hahn et al failed to demonstrate a significant effect of AZA on severe disease when added to glucocorticoids in early treatment.1 Subsequent studies by the NIH group showed only a trend to superiority of AZA with prednisone over prednisone alone; the studies, however, may have lacked power to detect a smaller treatment effect.2 Nevertheless, these results have led to considerable decrease in the usage of AZA for LN with the exception of some pediatric centers in Canada.

More recently, new studies have given us the opportunity to take another look into the effectiveness of AZA in the context of new therapeutic protocols and a modern standard of care. In a recent head-to-head comparison of AZA with intravenous CY (IV-CY), AZA showed comparable efficacy after a mean follow-up of at least five years.3 The use of intravenous methylprednisolone (IV-MP) pulses at the beginning of treatment for all patients in this study may have improved the performance of AZA. Strong, albeit circumstantial, evidence supports the use of one to three IV-MP pulses especially in patients with moderate or severe nephritis; in addition to expediting remission, IV-MP pulses may allow for the use of lower doses of glucocorticoids during the induction phase. Not surprisingly, patients in the AZA group experienced more flares and progression of scarring in repeat renal biopsies.3,4 Of note, the study involved only European, low-to-moderate–risk patients (see Figure 2 for definitions) treated in a context of the European healthcare system.

These data suggest that both CY and AZA are effective for treating LN but that CY is superior, especially for patients with aggressive disease. Another reading of this trial is that by employing more potent and thus potentially more toxic agents, some patients may be overtreated, whereas by using less potent agents some patients may be undertreated. This observation reinforces the need for stratification of patients according to disease severity.

Cyclophosphamide

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the NIH, with long-term (more than 10 years, sometimes as long as 20 years) follow-up in patients with predominantly proliferative LN, showed that CY regimens (daily oral or monthly IV pulses) in combination with glucocorticoids are effective in halting progression to ESRD. From these studies, protocols based on the use of high-dose IV-CY (0.75–1.0 g/m² per month) emerged as the gold standard for proliferative LN or membranous nephropathy with nephrotic-range proteinuria. The combination of pulse IV-MP and pulse IV-CY increased efficacy without added toxicity.5 In our studies, longer treatment protocols (seven monthly pulses followed by an additional eight every three months, for a total of 15 pulses) decreased the risk of flare as compared with shorter courses (seven monthly pulses), albeit at a higher risk for sustained amenorrhea (a three-fold increase in risk in women older than 26 years treated with a longer course of CY).

Subsequent efforts aimed to reduce the cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide by limiting its use to only induction regimen and by using lower doses. Trials led by Frédéric Houssiau, MD, PhD, in Belgium, involving exclusively European patients, have demonstrated the long-term efficacy of lower doses/shorter courses of IV-CY followed by the use of AZA for maintenance.6,7 As a result, the standard of care for most patients with proliferative LN has shifted. Thus, CY is being used currently only as induction therapy, with several European centers using the low-dose IV-CY and most North American centers using the NIH high-dose regimen. The difference in the cumulative dose of CY used in these protocols for an average person (body surface approximately 1.7 m2) is nearly four-fold (3 g in the low dose versus approximately 12 g in the high dose).

It is worth emphasizing that neither low-dose IV-CY nor MMF has been tried for the most severe cases of lupus nephritis. For patients with severe proliferative LN (defined as rapidly progressive nephritis or patients with impaired renal function or adverse histologic features such as fibrinoid necrosis, crescents, or significant chronicity) connoting a worse outcome, there is only a single RCT, published in 1992 in The Lancet and written by us, where high-dose pulse IV-CY was used.8 In this study and after five years, over 80% of patients treated with pulse IV-CY maintained renal function compared with only 50% of patients treated with pulses of IV-MP. A long-term (up to 15 years) follow-up of these patients confirmed the durability of the IV-CY effect.

Fallout of the NIH CY Trials

Based on its superior efficacy, pulse CY became the treatment of choice for severe lupus during the late 80s and 90s. Passionate debates at international meetings and editorials in leading journals pointed out the small number of patients participating in the NIH trials and warned against adopting the NIH regimen for all patients. In those debates, reasoning and moderation often seemed lost, with some people arguing that cyclophosphamide should never be used, while others failed to differentiate between severe and milder cases of LN and advocating universal usage of the drug. What some people failed to recognize is that not all patients treated with corticosteroids or AZA necessarily had a bad outcome and that differences among the various treatment arms did not emerge until after five years. Thus, although CY may be more effective than AZA or corticosteroids, some patients may be overtreated. On the other hand, the majority of patients would be undertreated if CY were not used.

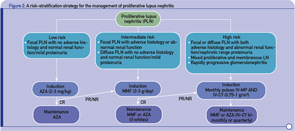

More recently, in an effort to reconcile divergent opinions and minimize the risk of over- or undertreating, we proposed a risk stratification scheme with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories (see Figure 2, p. 43). According to this approach, patients at higher risk for ESRD should be treated more aggressively, whereas those at lower risk can be treated less aggressively.9,10 Failure to achieve a major response within the first four to six months should evoke consideration for intensifying therapy. Although based on data originating from various centers, this strategy has not been evaluated in the context of a trial.

We should focus our efforts on developing a more comprehensive strategy to guide the treatment of lupus. This strategy should both “fit the patient” and achieve timely and long-lasting remission with the lowest possible harm.

Mycophenolate Mofetil

Although, in some centers, the intense debate regarding the use of CY continued until the end of the millennium, a “new kid on the block” by the name of MMF appeared from the field of transplantation. Thus, at the beginning of this decade, several RCTs with short-to-medium–term (up to five years) follow-up claimed that MMF has at least comparable—if not superior—efficacy to CY in the treatment of proliferative LN. These studies generated a great deal of enthusiasm, passion, and anticipation in the community, with several investigators declaring the end of the CY era in national and international forums. Soon, a large multicenter, multiracial RCT (the Aspreva Lupus Management Study, or ALMS) was conducted, aiming to demonstrate superiority of MMF as induction and maintenance therapy.11 Patients with class III-V LN were initially randomized to receive open-label induction therapy with MMF (target dose 3 g/day) or IV-CY (0.5–1.0 g/m2 in monthly pulses) in combination with corticosteroids (tapered from a maximum dose of 60 mg/day) for 24 weeks. Patients achieving response or complete remission (primary outcome) were subsequently re-randomized to double-blind, placebo-controlled maintenance treatment with MMF or AZA, both plus corticosteroids.12 For the maintenance phase, the primary endpoint was time to treatment failure (defined as either flares, need to intensify therapy, doubling of serum creatinine, or death).

The ALMS-induction trial did not detect significantly different response rates between the two groups. Of interest, MMF responses were better in certain racial/ethnic groups such as black-race and mixed Latin American (Hispanic) patients. During the maintenance phase, the investigators found a failure rate of 32% in the AZA group versus 16% in the MMF group at three years. In contrast, Houssiau and colleagues reported that MMF and AZA were comparable as maintenance therapy for proliferative LN in a multicenter European trial.13 While awaiting the full report on ALMS-maintenance to sort out whether these results reflect differences in the outcomes used (single in the MAINTAIN trial, composite in ALMS), the number (n=105 in MAINTAIN, n=227 in ALMS) or ethnic background of the patients, the MAINTAIN study clearly demonstrates equivalence between AZA and MMF in European patients with moderately severe LN.14

- Stratification of risk for progression to end-stage renal disease based on findings of longitudinal observational studies, and retrospective analyses of RCTs or clinical cohorts. Adverse histology denotes the presence of crescents and/or fibrinoid necrosis affecting >25% of glomeruli; glomerular sclerosis, tubular atrophy, or chronicity index >4; or chronicity index >3 and activity index >10. Impaired renal function denotes increase in serum creatinine or reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault or the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula) by >25%, or proteinuria >4 g/24 hr.

- Renal response is assessed at six months. CR is defined as decrease in proteinuria to <1 g/day (or <0.3 g/day in LN diagnosed in the past six months) with normal serum albumin concentrations; inactive urine sediment; and improved or stable renal function. PR is defined as significant change in proteinuria (if nephrotic at baseline ≥50% decrease in proteinuria to <3 g/day; if non-nephrotic at baseline but not meeting the CR criteria) and improved or stable renal function.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PR, partial response; NR, no response.

* All induction regimens include pulse IV-MP (1g/pulse ×3) followed by oral prednisone (0.5–0.6 mg/kg for the first four weeks of induction, then tapered).

Synthesis and Lessons Learned

The MMF studies have certainly taught us important lessons in trial design and have added a major new drug to the therapeutic armamentarium in lupus. On the other hand, they also have highlighted important shortcomings of MMF, such as failure of a significant number of patients (approximately 50%) to reach complete response; assessment of this agent is also limited by lack of long-term (beyond five years) follow-up. Although there is no head-to-head comparison between MMF and AZA as induction regimens, it is reasonable to assume that MMF could be the drug of first choice for induction of remission in moderately severe LN, especially in black and Hispanic patients. This recommendation is justified on the basis of better-quality data for MMF originating from large centers worldwide and clinical experience whereby a few patients refractory to CY may respond to MMF. This approach should not be perceived as abandoning AZA altogether. In our opinion, AZA may be used both as an induction therapy in milder LN cases in white patients and as maintenance therapy in most patients, except probably those with severe disease and certain racial/ethnic characteristics.

For patients with severe LN, the best available data support the combined use of pulses of IV-MP and IV-CY for at least six months or until a significant response or remission is achieved. Although not formally tested, a long course of IV-CY (15 pulses) may be effective in preserving renal function, as we have shown in our studies. Based on clinical experience and data from RCTs, we can assume that for patients with severe LN who achieve a complete renal response (i.e., normalization of creatinine and proteinuria less than 1 g/day), switching to maintenance therapy with AZA or MMF represents a reasonable option. For maintenance therapy, both agents may be used based on experience, availability, and issues related to the patient’s interest in, or potential for, pregnancy. Due to the significant difference in cost between the two drugs, patients with mild to moderate LN could be first treated with AZA, especially if they are white. In contrast to the data for proliferative LN, the data for MMF on membranous LN are limited to small retrospective cohorts, with some studies demonstrating efficacy while others fail to do so.

It is worth pointing out that while induction of complete response or remission generally occurs within three to six months in systemic vasculitis, it may take longer in LN (three to 36 months, with an average of 18 months in the NIH trials), with only 50% to 60% of lupus patients reaching this endpoint by six months. This delay in benefit poses a significant problem in the treatment of lupus especially in the case of MMF where there is no long-term experience with the outcome of such patients. In such cases treated with MMF, we usually add one to three pulses of IV-MP when a response has not yet occurred; if no further improvement is observed, we then switch to IV-CY. In the case of failure to respond to IV-CY, we also use pulse steroids and either wait for another six months or switch to MMF. If both agents have failed, we use rituximab in combination with MMF or IV-CY.

Perspective: Time for a Strategy in Lupus

Where do these trials leave us now? The excitement with new agents and anticipation of greater success are understandable, but we should guard against a premature declaration of their superiority. We should also be cautious about rushing to discredit old treatments that have served patients well despite their shortcomings. Importantly, clinicians, regulatory agencies, and industry need not lose sight of the lifelong course of the disease, and pursue long-term follow-up data to enable the full assessment of the safety and efficacy of the newer agents. To this end, it is rather disappointing that these data are not yet available for the MMF trials.

In our opinion, the most important information derived from lupus clinical trials is not necessarily the comparison among immunosuppressive agents, but rather the strategy for tight control of the disease, targeting disease remission if possible within the first six months, and its long-term maintenance (see Figure 2). Thus, almost every single trial has shown that, irrespective of the treatment used, a major response within the first three to six months is associated with a good long-term outcome.

Instead of debating the merits of individual agents, the community has come to agree that most patients should receive three pulses of IV-MP initially with moderate doses of steroids together with an immunosuppressive agent based upon the severity of the disease and patient choices/profile. Failure to achieve a major clinical response in the first three to six months should provoke consideration of advancing to more aggressive protocols. Towards this goal, combination and sequential use of existing agents is of paramount importance, as several RCTs have shown.

Consideration of the case posed at the beginning of this article illustrates these points. Thus, the patient clearly had moderately severe proliferative LN. A reasonable option would be to use three pulses of IV-MP followed by either AZA, MMF, or IV-CY, although most people would perhaps choose MMF as initial treatment because of the better data supporting the use of MMF versus AZA in this setting, and the potential for ovarian toxicity of IV-CY. Should the patient fail to achieve complete remission after three to six months of AZA or MMF, then she could be switched to a combination of IV-MP with IV-CY with protection of her ovaries.

In actual practice, the patient we described remitted initially with MMF but developed a severe nephritic flare with increase of her creatinine while on MMF. She was rescued with IV-MP and IV-CY pulses and reached remission after seven monthly pulses. While on maintenance quarterly IV-CY pulses, she had another flare of her nephritis and was switched to rituximab and MMF. She achieved remission after the second cycle of rituximab. She has subsequently been in remission for more than five years on 1 g/day of MMF and low-dose, alternate-day prednisone. Meanwhile, she was married and was switched to AZA because of her desire to have a family.

As this case shows well, current treatment of lupus nephritis poses many challenges and demands flexibility and willingness to try various approaches using data from well-conducted studies as a guide. While much needs to be done, for the future, we are optimistic that additional trials of biologics will be successful. Until that time, immunosuppressive drugs are here to stay. Optimization of the existing therapies by incorporating them in the best possible strategy is clearly the way to go.

Drs. Boumpas and Bertsias both work in Internal Medicine and Rheumatology, Clinical Immunology and Allergy, at the University of Crete Medical School in Greece.

References

- Hahn BH, Kantor OS, Osterland CK. Azathioprine plus prednisone compared with prednisone alone in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a prospective controlled trial in 24 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:597-605.

- Decker JL, Klippel JH, Plotz PH, Steinberg AD. Cyclophosphamide or azathioprine in lupus glomerulonephritis. A controlled trial: Results at 28 months. Ann Intern Med. 1975; 83:606-615.

- Grootscholten C, Ligtenberg G, Hagen EC, et al. Azathioprine/methylprednisolone versus cyclophosphamide in proliferative lupus nephritis. A randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2006;70:732-742.

- Gourley MF, Austin HA, 3rd, Scott D, et al. Methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide, alone or in combination, in patients with lupus nephritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:549-557.

- Illei GG, Austin HA, Crane M, et al. Combination therapy with pulse cyclophosphamide plus pulse methylprednisolone improves long-term renal outcome without adding toxicity in patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:248-257.

- Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: The Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:2121-2131.

- Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. The 10-year follow-up data of the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial comparing low-dose and high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:61-64.

- Boumpas DT, Austin HA 3rd, Vaughn EM, et al. Controlled trial of pulse methylprednisolone versus two regimens of pulse cyclophosphamide in severe lupus nephritis. Lancet. 1992;340:741-745.

- Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. Update on the management of lupus nephritis: Let the treatment fit the patient. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:464-472.

- Bertsias GK, Salmon JE, Boumpas DT. Therapeutic opportunities in systemic lupus erythematosus: State of the art and prospects for the new decade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1603-1611.

- Appel GB, Contreras G, Dooley MA, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1103-1112.

- Wofsy D, Appel GB, Dooley MA, et al. Aspreva Lupus Management Study maintenance results. Lupus. 2010;19:S27.

- Houssiau FA, D’Cruz D, Sangle S, et al. Azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil for long-term immunosuppression in lupus nephritis: Results from the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2083-2089.

- Boumpas DT, Bertsias GK, Balow JE. A decade of mycophenolate mofetil for lupus nephritis: Is the glass half-empty or half-full? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2059-2061.