Gordon Swanson/shutterstock.com

As healthcare delivery increasingly moves from volume-based care to value-based care, providers are needing to adopt new practices to meet what is now commonly referred to as the triple aim of healthcare delivery—improving the patient experience of care (which includes satisfaction and quality), improving the health of populations and reducing cost.1

Among the most difficult population of patients for which to achieve this triple aim is the group of patients with chronic, often multiple, conditions that incur a high burden and cost for both patients and the healthcare system. Among these patients are those with musculoskeletal conditions, as highlighted in a 2013 study, which found that musculoskeletal disorders were among the diseases associated with the highest levels of disability and burden of disease in the U.S.2 Thus, rheumatologists are among the providers who are particularly in need of finding ways to improve outcomes for their patients.

Accountable Care Organizations & More

Specific ways of better treating this population of patients are now being tested in a number of private and public program initiatives. Some familiar types of programs include accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes, readmission initiatives and care transition programs.

Data on these programs are now becoming available, with several recent reports shedding a light on what has worked well and what remains challenging.3-5 What emerges is a sense that what works at the micro-level works at the macro-level—that is, just as the best treatment for each patient is tailored to that patient’s individual needs, the best program appears to be the one that meets the particular needs of the population.

Douglas McCarthy, PhD, senior research director, The Commonwealth Fund, New York, a co-author of a 2015 report on outcomes data from a number of successful programs, emphasized that one type of program does not fit all circumstances.3 “New care models have a better chance for success if they are designed and adapted to meet the needs of particular population segments, payment arrangements and organizational settings,” he says.

In another report on successful programs published in 2015, Gerard F. Anderson, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Management, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, also highlighted the need to tailor programs to meet the needs of its population.4

“One of the key attributes [of successful programs] is the ability of the program to adapt to local situations,” he says. Providers are more apt to develop and implement successful programs than insurance companies because they know what their patients need and their circumstances require.

Key Features of a Successful Program

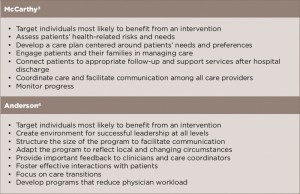

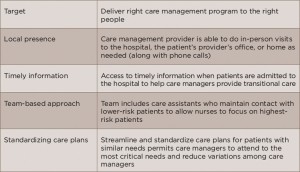

Both reports by Dr. McCarthy and Dr. Anderson highlight key features common to the programs they assessed that succeeded in improving patient outcomes and/or reducing cost (see Table 1, right).3,4

(click for larger image) Table 1: Common Features of Successful Programs to Treat High-Need, High-Cost Patients

As shown, an essential factor in both reports is correctly identifying patients who are high need and high cost and will benefit from an intervention. Also stressed are developing care plans or programs tailored to patients’ needs and circumstances, engaging patients and their families in their own care, and a focus on care coordination throughout care.

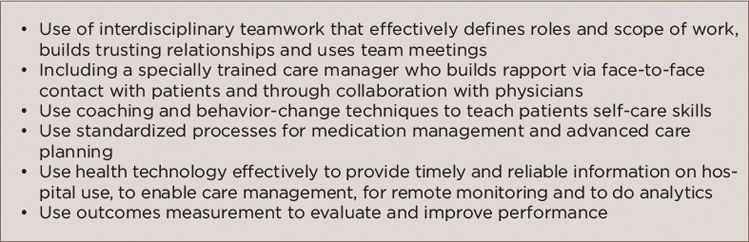

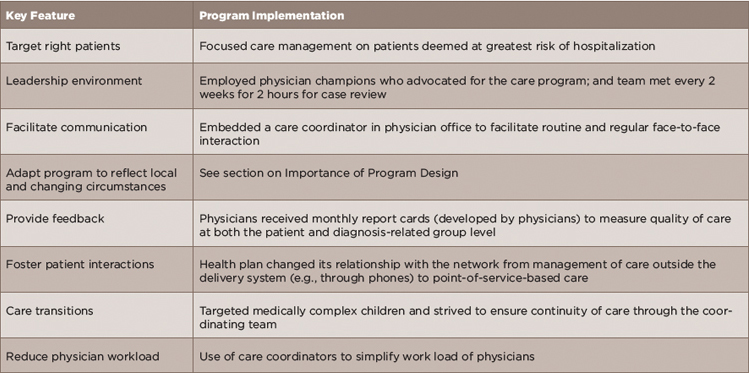

Both reports also include a list of how these key factors are implemented in a successful care program (see Tables 2 and 3, opposite). Table 2 provides a general list from the McCarthy report, and Table 3 provides a list of specific ways various programs implemented key attributes as described in the report by Dr. Anderson.

Importance of Program Design

As shown in Table 3, one of the key features for a successful program is adapting the program to reflect local and changing circumstances. This is highlighted by changes that one of the demonstration programs in the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration pilot undertook after initial outcomes failed to show reductions in Medicare spending and actually showed increased spending.6

(click for larger image) Table 2: Implementation of Key Features: How It’s Done

Source: Adapted from reference No. 3.

(click for larger image) Table 3: Examples of Specific Methods Used to Implement Key Features

Source: Adapted from reference No. 4.

Washington University of St. Louis School of Medicine (WUSM) was one of 15 demonstration programs selected to participate in the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration pilot. Mandated by the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration pilot tested whether providing coordinated care services to Medicare beneficiaries with complex chronic conditions under the fee-for-service model could improve patient outcomes without increasing cost. Under the pilot project, participating programs received care management fees from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in addition to Medicare payments for regular Medicare-covered Part A and B services for enrolled beneficiaries.

WUSM’s care demonstration program was initially implemented in August 2002 and ran through February 2006. Outcomes measured at that time showed that the care program did not reduce hospitalizations and in fact increased total Medicare spending by 12%.

The program was redesigned in March 2006 and included a number of changes: 1) using local care managers in St. Louis to contact (via phone and in person) all patients rather than using a remote site in California to call patients as was done in the original program design; 2) increasing in-person contacts (vs. phone contacts), especially focusing on patients considered at greatest risk of hospitalization; 3) expanding strong transitional care to all patients; 4) offering more comprehensive medication management for all patients; 5) including more thorough and systematic assessments of unmet medical and psychosocial needs; and 6) developing its own standard-of-care plans to better focus on specific conditions instead of using a care planning software program that was too broad and subjective.

Reassessment of outcomes in July 2008 showed that the redesign led to reductions in cost, both in terms of reduced hospitalizations (by 11.7%) and monthly Medicare spending (by $217 per enrollee).

“Our results show that delivering the right care management program to the right people can work,” write the investigators. “Serving high-risk patients with an intervention that incorporates strong transitional care, medication management, systematic assessments, focused care plans and the opportunity for in-person contacts by care managers with patients and providers reduced hospitalizations and Medicare spending.”6

(click for larger image) Table 4: Issues to Consider in Developing a Successful Care Program

Source: Adapted from reference No. 6.

Table 4 (right) lists a number of implications from the redesign of the WUSM care program that echo the suggestions provided in Tables 2 and 3 in implementing a successful care program.

Ongoing Challenges

Despite the success of these features and their implementation in improving patient outcomes, both Dr. McCarthy and Dr. Anderson cite barriers that remain in successfully achieving the patient outcomes (including satisfaction) and reducing cost.

“Health plans have been unable to successfully deal with many complex patients,” says Dr. Anderson, noting that plans often do not spend enough resources on getting the program in place, as well as not identifying patients who most likely will benefit from their program.

Dr. McCarthy also points to the lack of supportive financial incentives for programs that still have fee-for-service reimbursement arrangements, as well as the challenge of developing the capacity to make changes in practice (including training and new skills to take on new roles), putting a data infrastructure in place to share information among care team members in a timely way, and scaling up evidence from research pilot projects and trials to what will work in everyday practice.

Overall, Dr. McCarthy emphasizes keeping the focus on the patient when developing and implementing a program with an eye to improving patient outcomes and reducing cost.

Key Message for Providers

For rheumatologists and other providers who see patients with multiple chronic conditions, Dr. Anderson emphasizes the need to include someone who coordinates all of the care of each patient. “The care coordinator needs to look at the patient’s entire medical situation, their social needs and their economic situation to help them make the proper decisions,” he says, adding that rheumatologists need to address more than the rheumatologic concerns of these patients to provide sufficient care.

Dr. McCarthy also highlights the need to keep the needs and wants of the patient front and center. “Know your patients and redesign your systems and routines to meet their needs,” he says, adding that colleagues at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommend getting help from patients. “Enlist the help of five patients by asking them and their family members to share their experiences with healthcare,” he says, asking such questions as, “Where are they encountering frustrations? How can you improve the ways they get care and help them realize their goals for care?”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim Initiative.

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of US Health, 1990–2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013 Aug 14;310(6):591–606.

- McCarthy D, Ryan J, Klein S. Models of care for high-need, high-cost patients: An evidence synthesis. The Commonwealth Fund. 2015 Oct.

- Anderson GF, Ballreich J, Bleich S, et al. Attributes common to programs that successfully treat high-need, high-cost individuals. Am J Manag Care. 2015 Nov 10;21(11):e597–e600.

- Brown RS, Peikes D, Schore J, et al. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Affairs. 2012;31(6):1156–1166.

- Peikes D, Peterson G, Brown RS, et al. How changes in Washington University’s Medicare coordinated care demonstration pilot ultimately achieved savings. Health Affairs. 2012;31(6):1216–1226.