Kateryna Kon / shutterstock.com

BALTIMORE—Rheumatologists may not think about osteoporosis on a daily basis, but they should, said Dr. Karl Insogna, the Ensign Professor of Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine and director of the Yale Bone Center in New Haven, Conn., in his recent lecture at the Maryland Society for the Rheumatic Diseases.

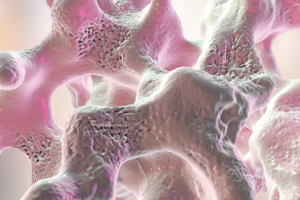

With approximately 75 million people in Europe, the U.S. and Japan suffering from osteoporosis, the condition is both common and, in many ways, complex in its pathophysiology. Dr. Insogna emphasized that under physiologic circumstances, the bone remodeling cycle is tightly coupled. This means attempts to inhibit bone resorption will ultimately inhibit bone formation as well, making it important to identify patients at risk for osteoporosis or in the early stages of the disease to prevent progression and address risk factors.

Patients with osteoporosis should be evaluated for hypogonadism, eating disorders, malabsorptive processes or inflammatory bowel disease, clinical signs of hypercortisolism, hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, Marfan’s syndrome, any family history of low bone mass, fragility fractures or unusual dental disease, and for use of medications, such as steroids, chemotherapy or heparin, that may contribute to disease. Dr. Insogna pointed out that height loss can be an important sign of osteoporosis, and that height loss of greater than 5 cm has been associated with fracture and an increased risk of all-cause mortality.1

Nonpharmacologic issues in osteoporosis can prove just as important as medications in the treatment and prevention of disease. For calcium, the goal daily intake is 2–3 mg per 1 kg of body weight to prevent insufficient calcium absorption and secondary hyperparathyroidism. For vitamin D, a total daily intake of 800–1,000 international units is recommended. Lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption can greatly contribute to the risk of osteoporosis, and exercise can effectively improve bone mineral density, particularly with regard to high-intensity resistance training and in patients at increased risk of osteoporosis, such as postmenopausal women.2

Zoledronic acid is the most powerful bisphosphonate.

Fracture Risk & Drug Therapy

Dr. Insogna discussed the World Health Organization Fracture Risk Assessment Tool, known to many clinicians as FRAX. This online calculator can be used to estimate the 10-year probability of fracture with bone mineral density.

Dr. Insogna said published drug trials to date have used only bone mineral density and not the FRAX score as the principal entry criteria and variable outcome. This means the literature may not demonstrate significant benefit of bisphosphonate therapy in patients with osteopenia of the femoral neck in the absence of osteoporosis of the spine, vertebral compression fracture or a prior fragility hip fracture—if the bisphosphonate under consideration is zoledronic acid.

Dr. Insogna noted that because increased bone breakdown appears to be the most common cause for accelerated bone loss, especially following menopause, the initial focus of drug discovery was inhibiting bone breakdown. Because the anti-resorptive agent alendronate is generic, inexpensive and effective, it is a good first-line therapy for compliant patients without significant heartburn or dysphagia history.

Risedronate is somewhat less potent than alendronate, but tolerance is better and patients tend to be more compliant compared to treatment with alendronate. Zoledronic acid is the most powerful bisphosphonate, and a 2007 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated a 35% risk reduction in clinical fractures.3

Dr. Insogna recommended physicians consider a drug holiday in patients after five-to-seven years of continuous therapy with an oral bisphosphonate, or after three years of zoledronic acid, so long as the bone mineral density has been stable and there has been no height loss or fragility fractures in the preceding year. Continuation of therapy with an agent such as alendronate may be indicated for patients older than age 76, those with greater than a 3% decrease in total hip bone mineral density after two years and those with a lower femoral neck T-score (i.e., -2.5 or less) at the end of five years of therapy.

More severe potential bisphosphonate side effects, such as atypical femur fractures or osteonecrosis of the jaw, are exceedingly rare, Dr. Insogna said. For example, for every 10,000 high-risk patients on bisphosphonate treatment, 100 hip fractures and 750 other fractures will be prevented with no more than three to six atypical fractures expected. Nevertheless, a thorough dental exam is recommended before starting bisphosphonate therapy, and it is important to listen to patients on therapy when they note femoral shaft pain—this should prompt further evaluation with a radiograph.

Dr. Insogna discussed several other medications for osteoporosis, including raloxifene (a selective estrogen receptor modulator), denosumab (a receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand [RANKL] inhibitor), and the parathyroid hormone teriparatide. He noted that advantages to teriparatide include the direct effects on the pathophysiologic issues in osteoporosis, namely the increase in osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis, the decrease in osteoblast number, the decrease in bone formation and bone strength and the reduced risk of vertebral fractures.

Conclusion

Rheumatologists should take note of the lessons imparted by Dr. Insogna given the number of older patients or individuals treated with corticosteroids in the typical rheumatology practice who may be at risk for, or already have, osteoporosis. It might be commonplace to “break a leg” in entertainment, but no such thing should ever occur unnecessarily in a clinician’s practice given our understanding of, and ability to treat, osteoporosis today.

Jason Liebowitz is a second-year fellow in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University. He earned his MD from Johns Hopkins University Medical School and completed his residency at Johns Hopkins Bayview. He has been published in JAMA Internal Medicine, The American Journal of Medicine, Medical Humanities, The Baltimore Sun and MedPage Today.

Jason Liebowitz is a second-year fellow in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University. He earned his MD from Johns Hopkins University Medical School and completed his residency at Johns Hopkins Bayview. He has been published in JAMA Internal Medicine, The American Journal of Medicine, Medical Humanities, The Baltimore Sun and MedPage Today.

References

- Hillier TA, Lui LY, Kado DM, et al. Height loss in older women: risk of hip fracture and mortality independent of vertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Jan;27(1):153–159.

- Watson SL, Weeks BK, Weis LJ, et al. High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2018 Feb;33(2):211–220.

- Lyles KW, Colón-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 1;357(18):1799–1809.