Many women share complaints of greater trochanteric pain with their healthcare providers. Their pain can lead to a diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy/enthesopathy and trochanteric bursitis, also known as greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS). Many clinicians believe that excessive compression plays an important role in the development of such insertional tendinopathies. Therefore, tests that mimic gluteal tendon compression, such as the single leg stance test, are sometimes used to help diagnose GTPS. More recently, the Patrick’s, or FABER, test has come into favor as a means of diagnosing GTPS during clinical examination. These tests rely on a lengthening of muscle fibers during flexion and external rotation.

Many women share complaints of greater trochanteric pain with their healthcare providers. Their pain can lead to a diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy/enthesopathy and trochanteric bursitis, also known as greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS). Many clinicians believe that excessive compression plays an important role in the development of such insertional tendinopathies. Therefore, tests that mimic gluteal tendon compression, such as the single leg stance test, are sometimes used to help diagnose GTPS. More recently, the Patrick’s, or FABER, test has come into favor as a means of diagnosing GTPS during clinical examination. These tests rely on a lengthening of muscle fibers during flexion and external rotation.

Although clinical tests can be used to diagnose GTPS, these tests have not been well evaluated in a clinical setting. As a result, clinicians often rely on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to diagnose GTPS, even though it has well-known limitations with regards to the diagnosis of tendon disorders. All told, there is a general acknowledgement that these tests may have limited accuracy and, consequently, result in misdiagnoses and ineffective interventions.

Charlotte Ganderton, MPhysio Prac, a physiotherapist at La Trobe University in Australia, and colleagues published the results of their evaluation of greater trochanteric pain online March 6 in the Journal of Women’s Health.1 They evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of 10 clinical tests of hip pathology used to diagnosis GTPS. The researchers examined these tests for specificity, predictive value and sensitivity to distinguishing patients with GTPS. The study included 46 women with a median age of 50.5 years. Of these, 28 had greater trochanteric pain and 18 were asymptomatic.

The investigators found that the most sensitive tests were a series of pain provocation tests: the Patrick’s or FABER test, palpation of the greater trochanter, resisted hip abduction and the resisted external derotation test. These tests all demonstrated high specificity for GTPS. In general, however, the diagnostic tests were better at ruling out GTPS rather than diagnosing it.

The rest of the tests evaluated by the study demonstrated only moderate accuracy. The inaccurate tests primarily involved isometric internal rotation and dynamic contraction from an externally rotated position to hip neutral. Although the standard or modified Obers tests have been described previously as useful diagnostic tests, the current study found them to have low sensitivity values for GTPS. The investigators proposed that the Ober’s test positioning may not provide enough tendinous compression to elicit pain.

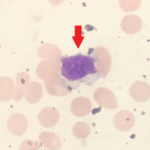

Physicians frequently use ultrasound and MRI to diagnose GTPS, but the researchers found that MRI yielded tendon pathology in both symptomatic (100%) and asymptomatic (88%) women. The pathological gluteal changes ranged from mild tendinosis to full-thickness tear, and the findings were consistent between both radiologist examiners. These results reinforce previously published reports of a poor association between tendon pathology and imaging and symptomatic tendon pain on clinical examination. Thus, the investigators concluded that radiological investigation with an MRI scan would likely not be useful in the management of GTPS.