Research is an essential tool to advance medical therapies and improve patient care, but to be most effective it requires comprehensive data that represent the full patient population. Unfortunately, as highlighted by recent studies, rheumatology suffers from a lack of demographically representative patient data in clinical datasets and from randomized clinical trials. In particular, a shortage of data from historically marginalized populations has created misunderstandings about rheumatic diseases and slowed development of therapies, particularly for such diseases as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus) that predominantly affect people of color.

Efforts to diversify data on rheumatic patients will require a commitment from researchers and practitioners to identify existing gaps in understanding and increase engagement of marginalized communities in research.

Dr. Sam Lim

Despite the dearth of diverse research data, S. Sam Lim, MD, knows the face of lupus well. A professor at Emory University School of Medicine and Rollins School of Public Health, Dr. Lim also works as the chief of rheumatology at the Grady Health System in Atlanta. “Grady is the only charity hospital in Atlanta and, given our area and the social forces at work, I predominantly see lower socioeconomic patients who identify as Black,” he says.

Dr. Lim had long considered his view of lupus patients skewed. After all, as he and co-author Cristina Drenkard, MD, PhD, wrote in a recent review, “As recently as the early 1950s … there was relatively little attention to race [of lupus patients], with the distribution of disease in the population being felt to be proportionate to the population under care at that time, which were mostly females with light hair, fair skin, and an inability to tan.”1

This perception has expanded since the first major population-based SLE study in the 1970s, but a complete picture of the lupus patient population is still developing. With a long history of volunteering with the ACR, where he has served on multiple committees and now serves on the Board of Directors, Dr. Lim is helping shape the rheumatology field’s perspective on lupus and its complicated relationship with racial identity. “New data coming from CDC lupus registries now show that my view of lupus at Grady is, in fact, the view of a typical lupus patient,” he says.

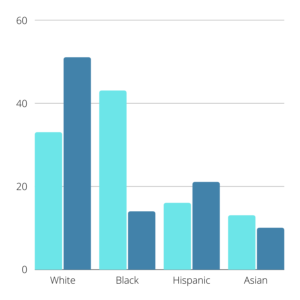

Figure 1: For each demographic group, light blue bars show representation among lupus cases and dark blue bars shows representation in randomized clinical trials. Data sourced from Falasinnu et al.

Research efforts have been slow to catch up, however. A 2018 article by Falasinnu et al. reported that whites were overrepresented in randomized clinical trials in the U.S., comprising 51% of trial enrollees but only 33% of prevalent SLE cases, while Blacks comprised 43% of prevalent SLE cases but only 14% of trial enrollees (Figure 1). Hispanics accounted for 16% of prevalent SLE cases and 21% of trial enrollees and Asians comprised 13% of prevalent SLE cases and 10% of enrollees.2

Lost Trust, Lost Representation

Many complex facets hinder the development of demographically balanced research. Trial researchers frequently face issues recruiting patients from underrepresented communities. Falasinnu et al. identified several system-level influences on minority recruitment in randomized clinical trials, including clinicians, hospitals and communities.2 In addition, historical acts of discrimination may have seeded distrust of the medical system among marginalized communities.

Dr. Irene Blanco

“There has been little acknowledgment of the horrific ways that medicine has been complicit in using Black bodies and people to forward science,” says Irene Blanco, MD, MS, professor and associate dean of the Office of Diversity Enhancement at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. Dr. Blanco co-leads the ACR’s new Diversity and Inclusion Task Force. “There is a feeling among the Black community that they are used as guinea pigs for untested treatments, which creates a serious roadblock for clinical trial recruitment. The Tuskegee experiment was not that long ago. It will take time to rebuild that trust.”

That lack of trust can translate into poorer health outcomes for Black patients. “Black patients who experience discrimination or perceive racism in healthcare report higher disease activity rates and higher rates of depression,” Dr. Blanco adds. “While the data available highlight the Black patient experience, we can extrapolate that other groups are also impacted by racism in healthcare, given the level of disparities that we see in other marginalized groups.”

Although structured differently than trials, registries may also lack diversity within their clinical datasets. Registries face the additional challenge of being opt-in opportunities for clinicians, making them vulnerable to self-selection by practices.

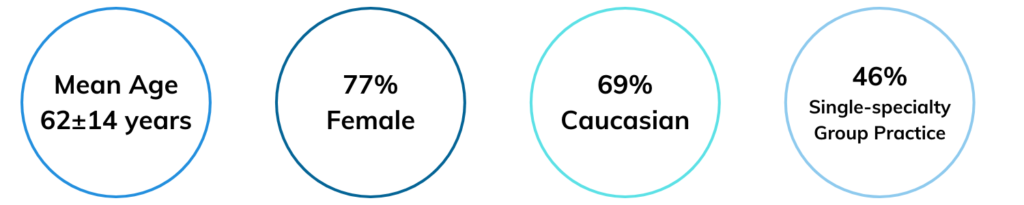

An analysis of the ACR’s RISE registry broke down the demographics of RISE rheumatoid arthritis patient data: The mean age was 62±14 years, 77% were female, 69% were Caucasian and 46% were seen in a single‐specialty group practice (Figure 2).3 The demographic issues outlined are representative of the overall dataset.

Figure 2: RISE registry demographic breakdown for rheumatoid arthritis patients. Data sourced from Izadi et al. findings.

“The fundamental challenge for RISE is that it was originally created for a specific purpose: to help practices survive in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and pay-for-performance world,” says William Harvey, MD, MSc, FACR, clinical director of rheumatology and associate professor at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. Dr. Harvey serves as the chair of the ACR’s Committee on Research and Health Information Technology (RHIT). “We are now fighting against that built-in skew … our current data are not properly representative of all rheumatic patients. We are evolving our messaging to highlight how RISE is not just for federal reporting, but for clinicians interested in other aspects of our field, such as quality improvement, research and data to support health policy.”

Dr. William Harvey

Toward this end, the ACR is now taking additional steps to expand the diversity of RISE users and data. “We are now trying to use the data to learn something about the care of individuals and practices, and with that aim, we are diversifying the registry to have a more representative sample,” Dr. Harvey adds. “What we need now is for more practices to participate and share their data with the ACR—the more RISE users we have from diverse sections of the clinical world, the more robust RISE research findings and conclusions will be.”

Taking Charge of Making Change

The RISE efforts are among several steps the ACR has recently taken to bridge diversity gaps in rheumatology. A new Diversity and Inclusion Task Force comprising member volunteers will advise ACR leadership and members. And through The Lupus Initiative, the College has developed various materials and other resources to help rheumatologists increase clinical trial diversity.

To assist with clinical trial recruitment, Drs. Lim and Blanco highlighted the importance of community health workers. These are typically members of marginalized communities who work with providers to improve patient outcomes.

Community health workers can serve as an important bridge to communities, says Dr. Blanco. “Because they are known figures and well-grounded in their community, their voices are given levels of legitimacy that outsiders struggle to receive. When a community health worker tells their neighbors about what you, as a clinician, are doing to help them, how you are investing in their community, those patients are more likely to take the risk of a randomized clinical trial.”

“It takes humility to go into high-risk populations and communities of color if you’re an outsider,” Dr. Lim says. “Abstracting data from a medical record is complex enough, but relatively that’s straightforward compared to getting patients to share their data and to feel comfortable in doing it. Community health workers play a vital role in this level of patient engagement.”

Research and clinician teams should also be composed of diverse members. As Dr. Blanco explains, “Investigators of color can see and articulate diversity-related topics and problems from a different standpoint. Having a diverse team can then point out issues in your science, but you also hope that they can help rebuild that community trust.”

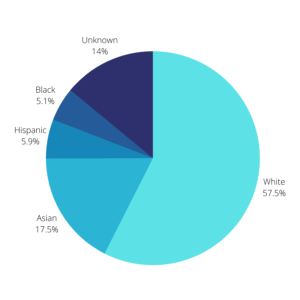

Figure 3: Self-reported demographics of active physicians in 2018. Data sourced from AAMC.

One challenge is that the medical field itself is demographically skewed. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, in 2018, 56.2% of active physicians identified as White, 17.1% identified as Asian, 5.8% identified as Hispanic and 5.0% identified as Black or African American.4 The race for 13.7% of active physicians was unknown (Figure 3). Increasing the diversity of the medical profession could help with clinical recruitment and clinical datasets.

“The pipeline is ridiculously leaky,” Dr. Blanco says. “The likelihood that the principal investigator of the study would be somebody underrepresented in medicine or the biomedical sciences is low. We must mentor and champion fellows, particularly fellows of color. If we can give those students the support they need as they navigate our rigorous system, we will be making a difference not just in their careers but in the lives and outcomes of their patients.”

Allison Plitman, MPA, is the communications specialist for the ACR’s RISE Registry.

References

- Lim SS and Drenkard C. Understanding lupus disparities through a social determinants of health framework: The Georgians Organized Against Lupus Research Cohort. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020 Nov;46(4):613-621.

- Falasinnu T, Chaichian Y, Bass MB, et al. The representation of gender and race/ethnic groups in randomized clinical trials of individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018 Mar 17;20(4):20.

- Izadi Z, Schmajuk G, Gianfrancecso M, et al. Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) Practices See Significant Gains in Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality Measures. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Sep 16:10.1002/acr.24444.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in medicine: Facts and figures 2019. Accessed March 17, 2021.