Lucky 7

With the subsequent availability of antibiotics, clinicians were able to successfully eradicate the causes of most fevers. However, it became evident that a sizeable percentage of patients with persistent fevers did not have an infectious cause. This observation was borne out by the classic study of unexplained fevers by Paul Beeson, MD, and Robert Petersdorf, MD, both professors of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.8 They proposed three broad explanations for a persistent fever, namely infection, cancer and what they referred to as the collagen diseases. All told, diseases within the purview of rheumatology accounted for nearly one-third of the patients in their study. This diverse group included patients with rheumatic fever, systemic lupus erythematosus, cranial arteritis, sarcoidosis, nonspecific pericarditis and what was referred to as periodic disease.

The periodic fever syndromes constituted a curious group: They were poorly understood and rarely seen or described in the literature. Working at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon, Hobart Reimann, MD, professor of medicine at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, had suggested the term periodic disease to describe a group of disorders “of unknown origin [that] often begin in infancy, recur uniformly at predictable times for decades without affecting the general health and resist treatment.”8 But this characterization was greeted with considerable skepticism. Perhaps this related to Reimann’s emphasis on the need for the febrile cycles of fever to last for seven days or some multiple of the number seven. In his words, “Seven always has had a special significance and looms large in folklore some cosmic association may be suspected.”8 Enough said!

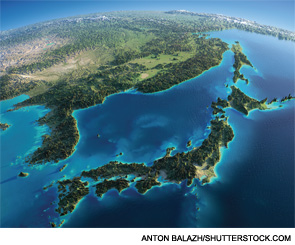

One explanation for the unusual geographical distribution of BD is that a genetic risk factor may have been propagated through previously isolated communities by itinerant traders or earlier pastoral nomads whose path across Asia was determined by the natural geographic features of the continents.

Horror Autoinflammaticus

Nearly a half-century later, a series of breakthrough discoveries made in London, England, laid the groundwork for our understanding of how immune regulation intersects with the febrile response. Using cells derived from family members afflicted by the TNFR1-periodic syndromes or TRAPS, the investigators described in elegant molecular detail, the germline mutations in the TNF receptor (TNFR1) that led to the development of this dominantly inherited syndrome of fever and widespread inflammation.

Around the same time, two groups of investigators, one multinational and the other based in France, independently identified the gene responsible for another periodic disease, familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). Because TRAPS and FMF are characterized by seemingly unprovoked, recurrent episodes of fever, serositis, arthritis and cutaneous inflammation, it was not a far-fetched idea to consider that these disorders might serve as prototypes for an emerging family of inflammatory diseases.9 The term autoinflammation was coined to distinguish these unique diseases from the more commonly observed autoimmune disorders. The key distinction between these two groups is the reliance of the former group on the phylogenetically ancient, hardwired, rapid-response innate immune system; whereas the latter group relies on the more plastic, adaptive immune system.