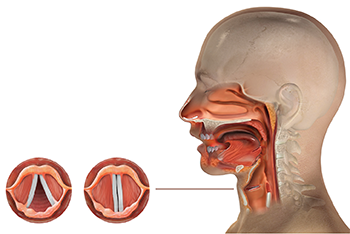

The Vocal Cords

Claus Lunau / Science Source

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome is a systemic autoimmune condition noted for findings of xerostomia, keratoconjunctivitis sicca and focal lymphocyte infiltrate in salivary glands.1 In the initial publications regarding keratoconjunctivitis sicca, Henrik Sjögren, a Swedish ophthalmologist, described a group of 19 women with dry eyes, some of whom had other organ dryness and inflammatory infiltrates.2,3 The syndrome that took his name can also involve extraglandular organs and include inflammatory arthritis, interstitial lung disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, primary biliary cirrhosis, vasculitis and blood dyscrasia. Laryngeal involvement is rare and is often missed as an initial manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome.4

Our Case

A 41-year-old Caucasian female with no significant past medical history was referred for rheumatologic evaluation by her primary care physician after she experienced fatigue, xerophthalmia (i.e., abnormal dryness of the conjunctiva and cornea of the eye, with inflammation and ridge formation), xerostomia (i.e., oral dryness), triphasic color changes in her digits with exposure to cold and stress, and dyspareunia (i.e., difficult or painful sexual intercourse). These symptoms had been progressively worsening over the span of 18 months.

The patient reported a history of difficulty speaking (i.e., dysphonia) that started six to 12 months before the previously mentioned symptoms developed. However, she was not evaluated by an otolaryngologist until after her rheumatologic workup was initiated.

On exam, the patient had evidence of xerostomia with poor oral dentition. She denied keeping up to date with dental hygiene. She was also found to have a noticeable dysphonia. No obvious parotid, submandibular or cervical lymphadenopathy was noted. Her cardiopulmonary exam did not reveal any abnormal findings. The musculoskeletal exam did not reveal obvious synovitis. No other mucocutaneous lesions were noted.

Laboratory data revealed a high-titer anti-nuclear antibody (1:640; homogenous pattern). Inflammatory markers (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) were within normal limits. Her complements were normal, and she was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s markers (e.g., anti-SSA, anti-SSB, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, anti-RNP and rheumatoid factor).

Given a high level of suspicion for Sjögren’s syndrome (with history of sicca symptoms and objective finding of xerostomia), she was referred to an otolaryngologist to pursue a minor salivary gland biopsy.

Upon the initial exam by the otolaryngologist, a flexible laryngoscopy was done to investigate her dysphonia. The exam revealed unilateral, complete vocal fold immobility. The minor salivary gland biopsy revealed inflammatory focus of greater than 60 inflammatory cells, confirming the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Treatment with 40 mg of prednisone and 300 mg of hydroxychloroquine daily was initiated. A steroid taper was suggested over six weeks.

The patient’s dysphonia and exertional dyspnea dramatically improved within one to two weeks after treatment was started. Repeat flexible laryngoscopy revealed normal mobility of both vocal folds and a complete recovery of the unilateral immobility.

Multiple follow-up flexible laryngoscopies showed lasting results, with normal vocal fold mobility after hydroxychloroquine was used as a long-term, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD). Cevimeline was used to help improve the xerostomia symptoms.

Referral to ophthalmology was placed for keratoconjunctivitis sicca. After she failed to use artificial tears regularly, the patient was placed on a cyclosporin ophthalmic solution, which significantly helped reduce her dry eye symptoms.

Discussion

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune condition characterized by xerostomia, keratoconjunctivitis and secretary dysfunction of lacrimal and salivary glands. It is about 10 times more frequently diagnosed in women than in men.1 The average age of individuals with Sjögren’s syndrome is about 56 years old.8 Extraglandular manifestations include inflammatory arthritis, interstitial lung disease, tubulointerstitial nephritis, cutaneous lesions and blood dyscrasia. Laryngeal involvement of Sjögren’s syndrome is rarely reported and is less likely the initial manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Laryngeal involvement of autoimmune conditions includes tissue ulceration or granulation, edema, cricoarytenoid arthritis, vocal fold immobility and bamboo nodes in the vocal cords. Laryngeal involvement has been reported in systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome and mixed connective tissue disease.5 Initial manifestations in the majority of these cases include dysphonia, asthenia (i.e., abnormal physical weakness or lack of energy), dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Most cases are treated with oral steroids, antacid and intralesional steroid injections. Oral steroids are the first-line treatment recommended by most experts, with speech therapy used as adjuvant therapy if needed.6 The most common DMARD used is methotrexate, in combination with oral and local steroids. In rare cases, endoscopic laryngeal surgery can be required after failure of oral and local steroid injections.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of evaluating connective tissue disorders in individuals who experience vocal fold mobility abnormalities. Although laryngeal involvement is not typical as an initial manifestation of connective tissue disorders, it can certainly be helpful with early diagnosis and a rheumatologic evaluation.

Although most other reported cases have used oral steroids and methotrexate for steroid-sparing effect, we chose hydroxychloroquine due to its minimal adverse effect profile in comparison with methotrexate and its known primary benefits in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Other potential benefits to improved dysphonia include better control of salivary gland dysfunction using sialendoscopy.7

This case highlights the importance of evaluating connective tissue disorders in individuals who experience vocal fold mobility abnormalities. Although laryngeal involvement is not typical as an initial manifestation of connective tissue disorders, its presence should prompt a rheumatologic evaluation.

Mohammad A. Ursani, MD, RhMSUS, is a rheumatologist practicing in a multispecialty group in North Houston. He has clinical interests in systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, musculoskeletal ultrasound.

Jaecel Shah, MD, is an otolaryngologist currently practicing in the North Houston area. His clinical interests include otolaryngological manifestations of connective tissue disease.

References

- de Paiva CS, Rocha EM. Sjögren’s syndrome: What and where are we looking for? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;26(6):517–525.

- Murube J. The first definition of Sjogren’s syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2010 Jul;8(3):101–110.

- Sjogren H. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca. In Trans Ophthalmol Section Swedish Med Association. 1929–1931. Acta Ophthalmol. 1932;10:403–409.

- Masarwa TO, Herold IH, Tabor M, Bouwman RA. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis following insertion of a supreme laryngeal mask in a patient with Sjogren’s syndrome. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2016;2016:8185628.

- Todic J, Schweizer V, Leuchter I. Bamboo nodes of vocal folds: A description of 10 cases and review of the literature. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2018;70(1):1–7.

- Ramos HV, Pillon J, Kosugi EM, et al: Laryngeal assessment in rheumatic disease patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Jul–Aug;71(4):499–503.

- Karagozoglu, Hakki, et al. Sialendoscopy enhances salivary gland function in Sjögren’s syndrome: A 6-month follow-up, randomised and controlled, single blind study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jul;77(7):1025–1031.

- Qin B, Wang J, Yang Z, et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Nov;74(11):1983–1989.