The Study Details

The prospective, observational study defined at risk as being ANA positive, having no more than one clinical lupus criterion (based on the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics [SLICC] classification criteria), symptom duration of less than 12 months and being treatment-naive.

The study included 118 individuals. Patient assessments included clinical, laboratory, blood and skin biomarker testing at baseline, 12 months and annually for three years. The researchers analyzed blood and non-lesional skin biopsies for the two ISG expression scores (i.e., IFN-Score-A and IFN-Score-B), and performed musculoskeletal ultrasound. They also looked for a family history of autoimmune rheumatic diseases among first- or second-degree relatives.

The study included 49 healthy controls and 114 lupus patients as negative and positive controls as well. The researchers defined progression as meeting the classification criteria for AI-CTDs at 12 months.

Of the 118 participants, 19 progressed to AI-CTDs, including 14 to lupus and five to primary Sjögren’s syndrome. At baseline, both IFN scores differed among at-risk individuals, healthy controls and lupus patients. In addition, both scores were elevated in at-risk patients who progressed to AI-CTDs at 12 months compared to non-progressors, and IFN-Score-B was elevated to a greater extent than IFN-Score-A. However, patients who progressed to AI-CTDs did not have significantly greater baseline clinical characteristics or ultrasound findings.

Fold difference between at-risk individuals and healthy controls for IFN-Score-A was markedly greater in skin than blood. According to multivariate logistic regression, only family history of autoimmune rheumatic disease and IFN-Score-B increased the odds of progression. Together with family history, IFN-Score-B from blood independently predicts progression and is a convenient biomarker for AI-CTDs, the researchers concluded.

Reliable screening for progression to an AI-CTD has several potential benefits for rheumatologists and their patients, says Dr. Yusof.

“[Because] the ANA test is sensitive, but not specific, for progression to AI-CTD, most rheumatologists usually wait until these individuals meet the classification criteria of the respective AI-CTD before [starting] treatment,” Dr. Yusof says. “For those who ultimately progress, heavy use of glucocorticoids is typically prescribed to induce remission, particularly in those patients with organ-threatening manifestations. By screening ANA-positive individuals for the two predictors of progression identified in our study—IFN scores and a positive family history of autoimmune rheumatic diseases—those with the imminent risk of relapse can be offered early treatment to prevent severe organ involvement, organ damage and glucocorticoid use.”

IFN-Score-B Is Independently Predictive

The study’s results showed some important differences in interferon status between the various groups. Both baseline blood IFN-Score-A and IFN-Score-B were elevated in patients who progressed to AI-CTD vs. non-progressors. However, the differences between these groups were greater, including narrower confidence intervals, for IFN-Score-B compared to IFN-Score-A.

“In the multivariable analysis, IFN-Score-B was independently predictive of progression, [so] it would be an important factor in the proposed screening approach,” says Dr. Yusof. “We also studied non-lesional areas of these ANA-positive individuals in order to compare IFN activities between blood and tissue. We were the first to show IFN activity was higher in this group compared to healthy controls. This finding also supports the measurement of IFN activity in blood [because] it is less invasive than skin biopsy.”

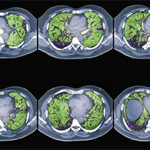

This was the first study to quantify IFN activity in the non-lesional skin of at-risk individuals. In their summary, the researchers point out that similar patterns of immune dysregulation were shown between skin and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). However, they found much greater fold differences in both IFN scores in the skin compared to the blood, so skin may be a potential site of AI-CTD initiation, they write.

Only a third of the at-risk individuals in the study who had ultrasound-defined synovitis progressed to AI-CTD within a year. Small numbers of asymptomatic patients with ultrasound-detected synovitis were also identified, so more work is needed to define the role of ultrasound in assessment of at-risk patients, they add.

The study also demonstrated, for the first time, that IFN activity is strongly associated with progression to AI-CTD independent of baseline clinical status, and further supports the use of the novel two-score system, says Dr. Yusof.

“IFN-Score-A comprised genes that were mainly responsive to IFN-1 stimulation, whereas IFN-Score-B comprised genes that responded to IFN type 1, 2, 3 and other inflammatory mediators that have yet to be unraveled,” he says. “Our results suggested that progression to AI-CTD might not be exclusively driven by IFN-1, but by a synergistic activation of genes induced by a range of interferons, as well as

other mediators.”

The study’s findings on the immune phenotypes of AI-CTD progressors may also help rheumatologists develop more effective therapies for these diseases in the future, Dr. Yusof says.

“Many targeted therapies in lupus have failed due to drug inefficacy, problems with trial design and inclusion of patients who predominantly have organ damage rather than active disease,” he says. “Thus, it is essential to immunophenotype these patients for a more personalized approach. The data presented in our paper [were] the initial biomarker discovery. The prognostic values of these IFN scores need to be replicated in a second cohort, which is in progress. Once these are validated, patients with imminent AI-CTD could be identified and offered earlier intervention using therapies that block IFNs or conventional immunosuppressants to avoid irreversible organ damage and glucocorticoid exposure.”