AMSTERDAM—With new therapies coming into the marketplace, researchers are working to tease out the risk of infection for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. Existing data suggest the risk of infections—even fatal ones—is real. But over time, improvements have taken hold, particularly for tuberculosis, according to an infectious disease expert at EULAR: the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

AMSTERDAM—With new therapies coming into the marketplace, researchers are working to tease out the risk of infection for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. Existing data suggest the risk of infections—even fatal ones—is real. But over time, improvements have taken hold, particularly for tuberculosis, according to an infectious disease expert at EULAR: the Annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

The precise infection risk posed by new biologic therapies can be an elusive data point, in part because most trials aren’t powered to detect them, said Olivier Lortholary, MD, PhD, professor and chair of infectious and tropical diseases at Hôpital Necker-Enfants malades in Paris. Mining health registries is often the best way to find answers, he said.

“It’s not so easy to decipher the relationship between biologics and infections during RA,” Dr. Lortholary said. “I want to emphasize the quality and the necessity of registries that are heterogeneous, but correspond to real-life patients with a bigger sample size for detecting rare events.”

Confounders in studies of RA patients include an increased infection risk even when untreated, co-morbidities that may pose an infection risk and being prescribed multiple immunosuppressive drugs, which make it even more tricky to determine the risk of an individual therapy.

In recent years, one of the most comprehensive looks at biologic therapy and infection risk in RA was a meta-analysis covering 70 trials. Investigators found biologic agents are linked to a “small, but significant risk [of infection],” having resulted in 1.7 excess infections per 1,000 patients treated.1

When pivotal trials are conducted, Dr. Lortholary said, infection risk can go undetected. Example: It wasn’t until infliximab had won approval and been in real-world use that the increased risk of tuberculosis was discovered.

The risk of infection associate with a biologic agent depends on a range of factors, including the drug’s presumed effect on the immune response, the drug structure, evidence found during experimental infections, and primary immunodeficiencies and the epidemiology of pathogens, Dr. Lortholary said.

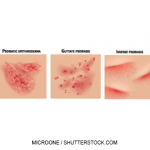

For tuberculosis, in particular, the risk is three to four times higher when a patient is on an anti-TNF drug, he said. So it’s important to start a tuberculosis-screening program, treat for latent tuberculosis and not restart anti-TNF drugs until clinical improvement, he said.

A recently published prospective observational cohort study from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Registry found the rate of tuberculosis among RA patients on biologic therapy plummeted from 783 cases per 100,000 patient-years in 2002 to 38 cases per 100,000 patient-years in 2015.2 Non-tuberculosis opportunistic infections were found at a rate of 134 per 100,000 patient-years. Researchers saw no differences in the overall rate of opportunistic infection between biologic drug classes, which included rituximab, anti-TNF and anti-IL6 therapies.