WASHINGTON, D.C.—Behçet’s disease (BD) is not a common condition, but we frequently receive referrals to evaluate for it in rheumatology clinics because a patient has oral or genital ulcers. So what’s Behçet’s and what’s not? How can we tell the difference?

At the ACR Convergence 2024 Review Course, Johannes Nowatzky, MD, director, New York University Langone Behçet’s Disease & Ocular Rheumatology Programs, Saul J. Farber associate professor of medicine, associate professor of pathology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, gave an exceptional talk on the differential for oral ulcers and more.

Not All Oral Ulcers Are Behçet’s

To illustrate this point, Dr. Nowatzky kicked off his talk with nine riveting cases, all of which included oral and/or genital ulcers. Only one of eight patients had BD. The others had mucosal erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, sarcoidosis and other conditions.

So which ulcers are BD and which aren’t? Oral ulcers are not specific, but are generally perceived to be mandatory for a diagnosis of BD. “The trick is to understand what type of lesions really count and what the clinical context is. You can’t make a diagnosis of BD from looking at oral ulcers alone because recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) looks exactly the same. However, you can often rule out BD by looking at the appearance of a mucosal lesion that is not an apthuous oral ulcer.”1

When trying to identify aphthous oral ulcers, three features can help. Ask yourself:

- Is there a yellow-white homogenous base?

- Is there a red halo around the outside of the lesion?

- Is it round or oval?

If the answer to all three questions is yes, then it could be an aphthous ulcer, which still has a differential diagnosis. If not, think of something other than BD and extend your differential diagnosis even further.

Not All Oral & Genital Ulcers Are Behçet’s

What about a patient with aphthous oral and genital ulcers? Definitely Behçet’s, right? Nope, not always. Oral and genital ulcers without extra-mucosal findings are better called complex aphthosis, a combination of RAS and genital ulcers. Menstruation, vitamin deficiency, zinc and iron deficiency, inflammatory bowel diseases and celiac disease are the most common causes of complex aphthosis in the U.S. BD is much further down the list in most practice settings here, and extra-mucosal manifestations should be present.

What about scarring after genital ulcers heal? Does that increase the chances of BD? “It does, but many types of genital lesions heal with scars, and that isn’t limited to BD,” noted Dr. Nowatzky. “In the U.S., many diseases, like hidradenitis suppurativa, vulvar Crohn’s and various forms of genital lichen can give you genital lesions that scar.”

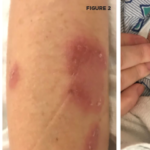

Skin Lesions

Skin lesions are common in BD, too, but also have low specificity. These may include nodular lesions caused by erythema nodosum or superficial thrombophlebitis, papulopustular and pustular acneiform lesions. When it comes to the latter, location is key. Dr. Nowatzky pointed out that pustular lesions often occur on the arms and legs in BD, as opposed to the face, as with pubertal acne vulgaris.

Of note, skin pathergy has high specificity for BD, but is not pathognomonic.

Major Organ Involvement

“Almost everything can be involved in BD, but the kidneys typically aren’t,” Dr. Nowatzky offered. He touched on central nervous system, GI tract, vascular and ocular manifestations of disease.

Neurologic BD comes in two flavors: dural venous sinus thrombosis or parenchymal (axial) neuro-BD. The latter usually involves the brain stem and adjacent regions, usually with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis and elevated CSF protein. “Parenchymal neuro-BD patients usually get recurrent disease and have a bad prognosis, but we can treat with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors these days,” he said.

As for the GI tract, Dr. Nowatzky noted that “it can be involved, but much less frequently than commonly assumed, especially in patients not of East Asian ancestry.” When BD does affect the GI tract, it causes deep, often solitary, ulcers that, unfortunately, have a predilection for the terminal ileum, as in Crohn’s disease, for example. Unlike Crohn’s disease, patients with BD have little to no colitis outside the immediate vicinity of the ulcers and a higher risk of bowel perforation.

When it comes to blood vessels, pulmonary artery aneurysms are nearly pathognomonic for BD, and hemoptysis is a very concerning sign of this. Other warning signs to be on the lookout for include unremitting headache (concerning for dural venous sinus thrombosis) and new-onset ascites (concerning for Budd-Chiari syndrome), or signs of deep vein thrombosis. “Fever, evidence of collateral vessel formation, pulsating tumors and superficial thrombophlebitis should also raise concern for vascular disease,” added Dr. Nowatzky.

As for the eyes, inflammation in BD is intra-ocular (i.e., uveitis). It’s important to remember that there’s always a differential diagnosis for eye disease, and location of inflammation helps narrow potential causes.2

“In the U.S., viruses (e.g., herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus and varicella zoster virus) are big on the differential,” Dr. Nowatzky noted, because “they can cause acute retinal necrosis which can mimic retinal disease in BD. However, an ophthalmologist experienced in uveitis can often diagnose BD by eye exam [because] the ocular phenotype of the disease can be specific.”

As for treatment of ocular inflammation, Dr. Nowatzky reminded us that “remission in BD eye disease must be evidenced by the absence of leakage on fluorescein angiography.”

Who Gets Behçet’s Disease?

“We all know that young male patients have the highest risk for severe BD, and patients with a family history are more likely to get the disease,” Dr. Nowatzky said. Allele frequencies for the commonly ordered HLA-B*51 are population dependent, and the prevalence of BD follows the allele frequencies of HLA-B*51 in the population.3 “HLA-B*51 percentages are highest along the Silk Road and decrease as you move farther away from it. In Turkey, for example, almost 30% of the healthy population carries HLA-B*51. As interesting as HLA-B*51 is for research purposes, it’s useless as stand-alone diagnostic tool,” he noted.4

Take-Home Points

Dr. Nowatzky wrapped up his talk with some high-yield points:

- The appearance of a mucosal lesions alone can break a diagnosis of BD but can’t make it.

- Oral and genital ulcers alone should be diagnosed as complex aphthosis, not BD.

- Diagnosing BD requires familiarity with its ocular and peripheral phenotypes, and with uncommon manifestations of more common diseases.

- Relying on HLA typing, other lab tests or histopathology to diagnose BD is not possible at present.

So remember, not all mucosal lesions are ulcers and not all ulcers are Behçet’s disease. A careful history and physical exam can help differentiate between them.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is a clinician educator who is passionate about the care and education of rheumatology patients. She writes for both medical and lay audiences and practices telerheumatology.

References

- Poveda-Galleg A, Murray PI, Rauz S, et al. How to recognise a Behçet’s ulcer from other types of oral ulceration? Defining Behçet’s ulceration by an International Delphi Consultation. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023 Oct;41(10):2048–2055.

- Corbitt K, Nowatzky J. Inflammatory eye disease for rheumatologists. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2023 May 1;35(3):201–212.

- Bordbar A, Manches O, Nowatzky J. Biology of HLA class I associated inflammatory diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2024 May;38(2):101977.