Rheumatologists and researchers who consider the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) the gold standard for measurement of self-reported health status may not want to give it up for a new system. However, the person who was instrumental in creating and launching the HAQ in 1980 says that the time is coming when it can be replaced with something much better, thanks to the National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) initiative.

James Fries, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California, is widely credited with creating the HAQ and is now a principal investigator on PROMIS. Since 2004, the PROMIS research initiative has been working to create a system of highly reliable, precise measures that can be used in clinical studies and in clinical practice to assess patient-reported health and wellbeing across a wide spectrum of chronic diseases and conditions.

PROMIS is in its second phase of funding and includes over 100 researchers at 13 sites. Studies at three of those sites are headed by rheumatologists: Dr. Fries at Stanford; Dinesh Khanna, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine and director of the scleroderma program at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; and Esi Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, assistant professor in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“Everyone is used to the HAQ,” Dr. Fries says. “Everyone knows what a patient looks like with a HAQ score of 0.8 and what that means when they read it in an article. The downside of introducing a new [instrument] is that we are saying that this new one is going to be better and will be enough better that you ought to be willing to make the change.”

Because of the years of work and new methodology used by PROMIS researchers, the “infrastructure of clinical science is improving,” representing a “shift in the paradigm about how you measure outcomes in rheumatic diseases. It’s an evolutionary shift, but its time has come,” Dr. Fries says.

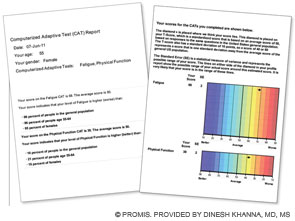

First section (left): Patient’s score for fatigue (where a higher score is worse) and physical function (where a higher score is better); her score is compared with the U.S. general population of women of the same age.

Second section (right): Graphic data showing that the patient’s fatigue is 1.8 standard deviations (SD) below the U.S. general population and that her physical function is 1.2 SD below the U.S. population.

This data can be used by the patient and her physician to establish her baseline self-reported health and in follow-up visits.

New Initiative Versus the Legacies

The HAQ was a “conceptualized” instrument, according to Dr. Fries. “We conceptualized the five D’s: death rates, disability levels, discomfort levels or pain, drug side effects, and the dollar cost. These would encompass all things that would be very important in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. … We used common sense to develop it as opposed to any science, and it transformed rheumatology.”

Since the HAQ was created, the science of item response theory (IRT) has developed, a science based on mathematical models that focus on the individual items rather than the total test or instrument. Also called “latent trait theory,” IRT is based on the idea that a latent trait is at the core of an illness and that this trait cannot be directly measured but can be indirectly assessed by individual items.1 Physical function is an example of a latent trait, in that “we know what it is and if you ask us, we can define it, sort of. We know it when we see it,” Dr. Fries says.

With IRT, the levels of a latent trait will depend on the person’s item-level responses rather than the score on the total instrument or test. An item’s properties ultimately characterize an individual and become an estimate of his or her unique functional status.2 Unlike fixed-length legacy tests, such as the HAQ, that were developed by classic test theory, an instrument created using IRT does not require that a patient answer a predetermined number of questions or items. Instead, the patient’s trait levels can be estimated with any subset of items appropriate to that patient from a pool of items—a process that requires much less time to complete.

The PROMIS initiative is developing self-reported measures of not only physical functioning but also of other domains, including fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and social health. Item banks, now available at www.nihpromis.org, can be used to assess pain behavior, fatigue, sleep disturbance, anger, depressive symptoms, and other domains that apply to patients with rheumatologic and other chronic conditions.

Assess More Symptoms Quickly

PROMIS’s intent is to develop, evaluate, and standardize item banks to measure patient-reported outcomes across various medical conditions, Dr. Khanna says. “You are able to assess many more symptoms or aspects of disease—whether physical, mental, or social functioning—and assess them using a very few number of items. An item bank such as physical function may have 124 items, but, on average, people just need to complete seven or eight items.”

A major goal is that the reliable and valid item banks can be administered as computer adaptive testing (CAT), which means that the computer program will select the most informative questions for a particular patient based on each previous response, thus using a minimum number of questions that the patient needs to answer. A patient gets the first question and then a second question, unique to that patient, that is based on the response to the first question; a third question follows that is based on the answers to the first two questions.

Dr. Khanna and colleagues have assessed use of 11 CAT-administered PROMIS item banks among patients with scleroderma at a single center. They found that the average time to reliably complete the 11-item bank domains was about 11.9 minutes, or about one minute per domain. In comparison, Dr. Khanna says, a patient would spend about 18 to 30 minutes completing the 91 items in the five legacy instruments that assess six domains in patients with scleroderma (physical functioning, mental health, bodily pain, social functioning, sleep, and fatigue; manuscript in review).

Dr. Morgan DeWitt is principal investigator on another PROMIS research initiative, called Enhancing PROMIS in Pediatric Pain, Rheumatology, and Rehabilitation Research. The research is validating the pediatric measures that were developed in the first phase of PROMIS. “We’re taking the PROMIS 1 measures that were developed in pediatrics among a large cohort of both healthy kids and kids with chronic conditions and doing longitudinal validation in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [JIA] or chronic musculoskeletal pain,” she says.

The items developed in phase 1 are now being administered along with legacy scales at three different time points to children with JIA or chronic pain; this is coupled with clinical measures of disease activity, such as joint counts or global assessments. “This enables us to study the responsiveness of the PROMIS measures to changes in a patient’s clinical status. The results will facilitate the use of PROMIS measures for assessment of health outcomes over time. By determining how large of a change is clinically important, this will increase interpretability of change scores and the usefulness of the measure in these particular populations,” she says.3

“With PROMIS, we have a wide range of domains of health-related quality-of-life measures—such as fatigue and pain interference—that we haven’t previously had for children with JIA. Another goal of the research is to develop new measures to assess the multiple dimensions of pain in children with new pain behavior and pain quality items to test in patients with JIA, fibromyalgia, and sickle cell disease. “Currently there is a pain interference measure, but we don’t have other ways of measuring pain,” says Dr. Morgan DeWitt.

18 Steps in Question Development

The science of IRT requires 18 steps for item development, according to Dr. Fries. His PROMIS research, called Improving Assessment of Physical Function and Drug Safety in Health and Disease, first required looking at all of the last 30 years of published articles written in English about instruments related to quality of life. That yielded 165 questionnaire instruments with 1,860 items that related to disability or physical function health outcomes. Through the process of “binning and winnowing,” items were grouped that were similar and redundant items were tossed out, leaving about 154 items.

The next step is talking to many people in the field, asking if they understand the questions, asking translators whether the questions can be misunderstood or misinterpreted in different languages or cultures, and working to neutralize any unintended cultural implications. After the qualitative stage of item development, which includes figuring out how to improve the items as much as possible, the quantitative stage begins, which involves research about which items convey the most information over time.

As part of their PROMIS research, Dr. Khanna and colleagues are now working on development and validation of gastrointestinal symptoms in chronic medical conditions, and they have developed a preliminary item bank. They, like other PROMIS research groups, are following the same 18 steps for item development and validation.

Crosswalking is another “non-trivial step in the process,” according to Dr. Fries. The crosswalk estimates the score on a new instrument or on one item from scores on another, and back again. Through crosswalking, the physician “will be able see what [the new score] would have been on the old scale that he is used to. It’s a lot of grunt work. The point is that you are building from the ground up; you are doing everything you can to have better items. You get better instruments from better items,” he says.

In phase 2 of the research, validation studies began. “We are now asking, ‘Are these instruments better than the old instruments?’ That’s the gutsy question to ask,” he says.

Recommended Reading

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179-1194.

- Irwin DE, Varni JW, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:3.

- Morgan DeWitt E, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: Built using item response theory. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:794-804.

- Spiegel BMR, Khanna D, Bolus R, Agarwal N, Khanna P, Chang L. Understanding gastrointestinal distress: A framework for clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:380-385.

Impact of PROMIS on Clinical Practice

The potential impact of the PROMIS research on clinical practice should be significant, according to Dr. Morgan DeWitt, who says that both the ease of electronic administration and the brevity of the instruments are two major advantages. Currently at her hospital, quality-of-life measures are not always reliably administered. Because they are paper based, they are often not available when the physician sees the patient in his or her office.

With the new system, the patient could respond to the items quickly on a handheld device such as a Smart Phone or tablet, or on a laptop the day before the office visit, or even at the office. The scores would be immediately available, calibrated to the population norm, and ready for the visit with the physician.

“With these instruments, we would be able to see how much impact pain is having on the patient’s life and more accurately see the burden of disease. Then as we treat them, we can see the changes or improvement relative to the population norm by administering the item banks at each visit,” Dr. Morgan DeWitt says. The PROMIS instruments are expected to be less taxing for ailing patients to complete, with more precise information across a wide variety of chronic conditions and diseases.

Another advantage with the new system is that abilities related to physical functioning can be measured when they exceed the average. According to Dr. Fries, some patients with rheumatic arthritis who are getting advanced therapies now have abilities that are above average. Current scales miss that improvement, which would be important information for both the clinician and to researchers who are evaluating a specific therapy.

Tools created by the PROMIS initiative are expected to outrank legacy scales in flexibility, in that they can be administered in a variety of ways and in different forms.

Clinicians and researchers can access PROMIS instruments (short forms, CATs, and profiles) in the instrument library found at http://assessmentcenter.net. These item banks are in the public domain, as are the PROMIS short forms of 4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, and 20-item length. Any measure can be downloaded for paper administration or be included in an online study. Visitors to the site can take a demonstration CAT on domains related to emotional, physical or social health. Each completed demonstration is followed by automatic scoring and rating. the rheumatologist

Kathy Holliman is a medical journalist based in New Jersey.

References

- Fries JF. Items, instruments, crosswalks, and PROMIS. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:6.

- Bruce B, Fries JF, Ambrosini D, et al. Better assessment of physical function: Item improvement is neglected but essential. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009:11:R191.

- Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. PROMIS pediatric pain interference scale: An item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank. J Pain. 2010;11:1109-1119.