Editor’s note: Read more about this research in a paper by Dr. Pincus and colleagues in our sister publication, Arthritis Care & Research.

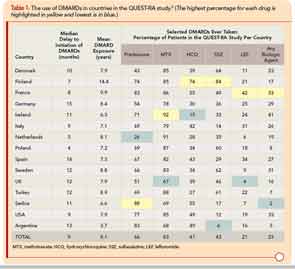

Textbooks of rheumatology and recommendations of professional societies have long suggested that glucocorticoids in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) should be used primarily as “bridging therapy,” while awaiting the benefits of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and/or in acute emergencies such as life-threatening vasculitis or vision-threatening scleritis. Recent EULAR recommendations reflect this directive.1 Nonetheless, many RA patients treated by rheumatologists take low-dose prednisone on a long-term basis. For example, in the international database of the Quantitative Clinical Assessment of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (QUEST-RA) study, among 4,363 RA patients seen in usual care at 48 clinical sites (approximately 100 patients per site) in 15 countries, 66% of consecutive patients took glucocorticoids, including more than 70% in Argentina, Finland, France, Ireland, Serbia, and U.S., and more than 50% in seven other countries—all but Denmark (43%) and the Netherlands (26%) (see Table 1).2 Therefore, rheumatologists’ experience suggests that long-term prednisone may be desirable for many, if not most, patients with RA.

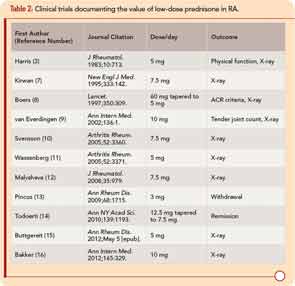

Extensive use of low-dose prednisone at this time appears based in part on a reassessment of glucocorticoid therapy that began during the 1980s, with concurrent recognition of severe long-term outcomes of RA.3-5 The efficacy and safety of low-dose prednisone was documented in an open study reported in 1964, and a 24-week clinical trial reported in 1982.3,6 Since 1995, 11 double-blind RA clinical trials have provided strong evidence for the efficacy and safety of prednisone in doses of 10 mg/day or less over two years or less compared to a placebo.7-16 A withdrawal clinical trial documented clinical efficacy of prednisone in doses of 3 mg/day compared to placebo (see Table 2).13 Disease-modifying properties of low-dose prednisone or prednisolone of 5 mg/day, confirmed in meta-analyses, are of particular interest, as doses of 7.5–10 mg/day are associated with adverse effects and outcomes, including bone loss and higher mortality rates.3,11,17-22

I have summarized treatment of RA patients with prednisone over 25 years between 1980 and 2004 at a weekly academic clinical setting, almost always with concomitant methotrexate after 1985.23-25 A database of all visits of all patients included medications; scores on a multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) for functional status, pain, and routine assessment of patient index data (RAPID3); and self-report of possible adverse effects.26

Of course, observational data are affected by limitations not seen in randomized data. However, it is not possible, logistically or ethically, to maintain randomization in symptomatic patients with RA over periods longer than two years.27 Therefore, accurate knowledge concerning the safety and effectiveness of long-term treatment of RA with prednisone <5 mg/day requires observational data to complement clinical trials, as summarized below:28

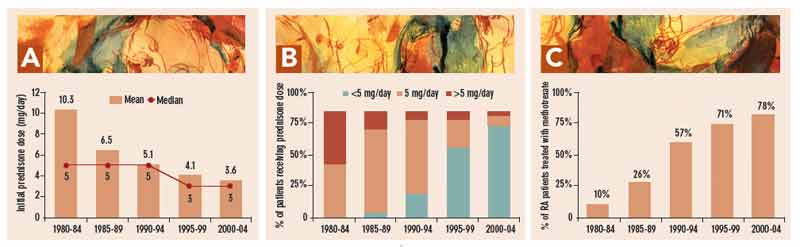

The mean initial prednisone dose in 308 patients with RA treated between 1980 and 2004, analyzed in five-year periods, declined from 10.3 mg/day in 1980–1985 to 6.5 mg/day in 1985–1989, 5.1 mg/day in 1990–1994, 4.1 mg/day in 1995–1999, and 3.6 mg/day in 2000–2004 (see Figure 1a, p. 23). The proportion of patients whose initial dose was <5 mg/day increased from zero in 1980–1984 to 4% in 1985–1989, 23% in 1990–1994, 67% in 1995–1999, and 86% in 2000–2004 (see Figure 1b, p. 23). The proportion treated initially with 5 mg/day was 51%, 80%, 70%, 26%, and 10%, in the five-year periods, respectively. The proportion treated initially with >5 mg/day was 49%, 16%, 7%, 7%, and 3%, in the five-year periods, respectively (see Figure 1b, p. 23). Over this period, the proportion of patients treated with methotrexate rose from 10%, to 26%, 57%, 71%, and 78% in the respective five-year periods. (see Figure 1c, p. 23).23

Higher mean initial prednisone doses were administered to patients with greater disease severity. In patients treated with ≥5 mg/day, the mean baseline MDHAQ physical function score was 3.5 (0–10 scale), mean pain score 6.3 (0–10 scale), and mean RAPID3 17.3 (0–30 scale) versus 2.4, 5.2, and 13.2, respectively, in patients treated initially with <5 mg/day.25

Improvement in clinical status over 12 months for MDHAQ function, pain, and RAPID3 was similar in patients with initial dose ≥5 mg/day—40%, 37%, and 38%, respectively—compared to patients with initial dose <5 mg/day, in whom improvement was 34%, 37%, and 37%, respectively.25 Therefore, the 86% of patients treated with <5 mg/day in 2000–2004 experienced benefit similar to those treated with higher doses, albeit that their clinical status was milder.5 These data reflect confounding by indication that patients with more severe disease received higher prednisone dose.

Clinical improvement was maintained for up to eight years in most patients.25 These findings differ considerably from those in the 1980s and 1990s, when initial improvement was followed by progressive declines in clinical status after two to three years in most patients.5,29

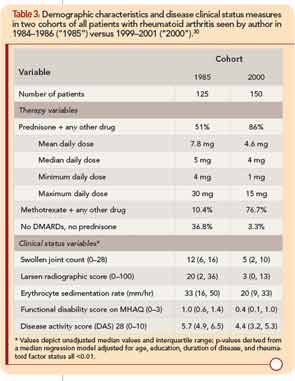

Substantially better clinical status was observed in all 150 RA patients seen by the author in 2000 compared to all 125 patients seen in 1985, according to MDHAQ function, swollen joint count, radiographic damage, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and other measures (see Table 3, p. 22).30 In 1985, 51% of patients were taking prednisone with a mean daily dose of 7.8 mg/day, 10% were taking methotrexate, and 37% no DMARDs or prednisone. In 2000, 86% were taking prednisone at a mean dose of 4.6 mg/day, 77% were taking methotrexate, and only 3% were taking no DMARDs or prednisone (see Table 3).

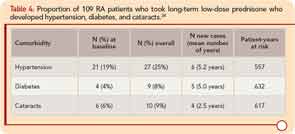

The primary adverse events in patients treated with <5 mg/day prednisone were bruising and skin thinning. There were six new cases of hypertension over a mean of 5.2 years in 88 patients over 557 patient-years, five new cases of diabetes over a mean of 5.0 years in 105 patients over 632 patient-years, and four new cases of cataracts over a mean of 2.5 years in 103 patients over 617 patient-years (see Table 4). Mean (median) weight gain was 1.45 kg (1.13 kg) over 48 weeks. Weight gain was lowest in patients who began prednisone ≤3 mg/day (mean 0.44 kg), and greatest in patients who began prednisone >5 mg/day (mean 2.63 kg).25

All patients who were treated with prednisone at any dose were offered an opportunity to discontinue their prednisone, in a tapering schedule of 1 mg/month or 1 mg every two months, with a schedule to take, say, 3 mg on odd days and 2 mg on even days. Most patients tried this at least once, often several times, as many of their other physicians, and often their spouses, neighbors, and relatives all urged them to “stop taking that prednisone that Dr. Pincus is giving you.” The main reason expressed by patients for nonparticipation in the prednisone withdrawal clinical trial was that they had already attempted to discontinue prednisone many times and wished not to be randomized to placebo.13 Some elderly women reported having bruises and skin thinning, and related that they were forced to wear long sleeves so that people “would not think that my husband was beating me.” Nonetheless, most patients elected to continue long-term prednisone in doses of 1–4 mg/day, as a “trade-off” of minimal adverse events appeared justified to maintain functional status and well-being.

An example of a person with RA who was treated with prednisone 3 mg/day and methotrexate 10 mg/week is presented in a flow sheet from actual care (see Figure 2) The patient initially self-reported scores for physical function of 3.3 (0–10), pain 9.5 (0–10), global status 9.5 (0–10), and a RAPID3 score of 22.3 (0–30), indicating high severity (>12). Two months after initiation of prednisone 3 mg/day and methotrexate 10 mg/week, his RAPID3 score was 1, indicating near-remission. He was stable over a year, but experienced a severe flare 13 months after initial presentation, with a RAPID3 score of 11.5, at the upper limit of moderate severity (6–12). After lengthy discussion with the patient and his family, he chose to be treated with adalimumab and an intramuscular injection of 40 mg methylprednisone. Two months later, all his scores were 0. Throughout this period, his daily prednisone dose was maintained at 3 mg/day although, as noted, he was given an intramuscular injection at the time of a severe flare.

The case for treatment with prednisone in doses of 5 mg/day or less includes:

- Documented efficacy in clinical trials of 5 mg/day, and 3 mg/day in a withdrawal clinical trial.3,11,13

- Doses of 5 mg/day or less generally are well tolerated.

- Doses of 5 mg/day are physiologic rather than pharmacologic, are incremental to normal endogenous production of glucocorticoids to maintain homeostasis, and do not lead to suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.31 Therefore, discontinuation does not lead to adrenal insufficiency or possible adrenocortical crisis.

- A prescription of 1–4 mg/day in 1-mg tablets allows a patient to titrate her/his own dosage to find an optimum level, with a minor (1- or 2-mg) increase when needed. Ironically, 1-mg tablets are more expensive than 5-mg prednisone tablets, but even prednisone 1 mg is one of the least expensive medications for a patient with RA.

- Over long periods, adverse events associated with 5 mg/day in clinical care are no greater, and may even be lower than expected.20

The case against prednisone in doses greater than 5 mg/day includes:

- Short-term doses of greater than 5 mg/day, especially of 20 mg/day even briefly, may be associated acutely in some patients, albeit infrequently, with adverse events including restlessness, irritability, insomnia, increased appetite, weight gain, and psychosis—effects almost never seen with 5 mg/day, which provides similar efficacy.25

- Although doses of 7.5–10 mg/day appear to have no more, and in some cases even fewer, adverse events than placebo in short-term studies over two years or less, over 5 years or longer, doses greater than 5 mg/day are associated with higher rates of hypertension and diabetes, infection, and increased mortality rates.7,10-12,15,16,20-22,32

- Doses greater than 5 mg/day taken over two to three weeks led to suppression of the HPA axis, requiring “coverage” if the patient experiences surgery, trauma, and/or other stressful events.

Discussion

The use of 3 mg/day in RA appears to provoke as much controversy as whether or not patients should take glucocorticoids at all. Advocates of glucocorticoids in RA suggest that 3 mg/day is an inadequate “placebo” dose which is within physiologic production under normal circumstances. By contrast, opponents of glucocorticoids in RA suggest that any glucocorticoid is harmful, so why expose a patient to 3 mg prednisone per day, particularly if regarded as a “placebo-type” dose? Perhaps, as in many compromises, if neither side finds the compromise satisfactory, it might be worthy of consideration.

The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 3 mg/day prednisone (or any medication) might ideally be documented in a randomized controlled trial protocol. However, it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a randomized study in RA over longer than two years, while effectiveness and safety data over five to 15 years are needed. Therefore, observational data are needed.

Improvements in methodologies of both observational studies and clinical trials will advance knowledge concerning long-term use of <5 mg/day of prednisone. However, logistic, medical, and ethical considerations would require that multiple therapies be provided to patients to achieve best outcomes. Therefore, it may never be possible to isolate prednisone (or methotrexate, biological agent, physical therapy, or any single variable in a “reductionist” mode) in treatment of RA (or any chronic disease) over five years or longer. This limitation should not deter efforts to identify optimal strategies for low-dose prednisone to achieve better care and outcomes for patients with RA and all inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

A most important consideration in collecting and reporting observational data is to try to include all consecutive patients, to avoid patient selection. A database of consecutive patients provides data relevant to patient care that are not available through randomized controlled clinical trials.28 All data presented in this article concerning prednisone use over 25 years are based on only a simple one-page, two-sided MDHAQ, given by a receptionist to each patient at each visit while waiting to see the doctor. This practice requires minimal financial support or logistic complexities, and captures data concerning >99% of visits with simple “quality control” by doctor review with each patient, saving time for the doctor with information on the MDHAQ concerning self-report joint count, review of systems, and recent medical history.

Any rheumatologist can use this procedure to assess results of therapy over short or long periods. The best software and/or statistician cannot help clinicians learn about results of therapy if the data are not collected. Any visit without quantitative data is a lost opportunity.

Many patients with rheumatic diseases may have a prognosis for disability and mortality as severe as patients with primary cardiovascular or malignant diseases. It is up to rheumatologists to document that effective and safe therapies can reverse poor prognosis in usual clinical care. Of course, resources are needed to analyze databases. This need should not deter collection of an MDHAQ at each visit, which also prepares the patient for the visit, improves doctor–patient communication, and saves time for the doctor.

In conclusion, long-term low-dose prednisone, at doses of <5 mg/day, appears feasible and effective for many patients with RA, including initial dose of 3 mg/day and indefinite continuation. Recommendations for glucocorticoid therapy were developed initially during the 1950s, when glucocorticoids were the only available major antiinflammatory therapy. However, most patients with RA or other inflammatory rheumatic disease in contemporary care are (or should be) treated with concurrent methotrexate, other DMARDs, or cytotoxic therapies, and lower prednisone doses are adequate. Current practice may include doses of prednisone (much) higher than needed for many patients with any inflammatory rheumatic disease.

Dr. Pincus is clinical professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at New York University School of Medicine and NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York City.

References

- van der Goes MC, Jacobs JW, Boers M, et al. Monitoring adverse events of low-dose glucocorticoid therapy: EULAR recommendations for clinical trials and daily practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010; 69:1913-1919.

- Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Toloza S, et al. QUEST-RA: Quantitative clinical assessment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis seen in standard rheumatology care in 15 countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1491-1496.

- Harris ED, Jr., Emkey RD, Nichols JE, Newberg A. Low dose prednisone therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: A double blind study. J Rheumatol. 1983; 10:713-721.

- Scott DL, Grindulis KA, Struthers GR, Coulton BL, Popert AJ, Bacon PA. Progression of radiological changes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:8-17.

- Pincus T, Callahan LF, Sale WG, Brooks AL, Payne LE, Vaughn WK. Severe functional declines, work disability, and increased mortality in seventy-five rheumatoid arthritis patients studied over nine years. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:864-872.

- de Andrade JR, McCormick JN, Hill AGS. Small doses of prednisolone in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1964;23:158-162.

- Kirwan JR. The effects of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:142-146.

- Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1997;350:309-318.

- van Everdingen AA, Jacobs JWG, van Reesema DRS, Bijlsma JWJ. Low-dose prednisone therapy for patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical efficacy, disease-modifying properties, and side effects. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:1-12.

- Svensson B, Boonen A, Albertsson K, van der Heijde D, Keller C, Hafstrom I. Low-dose prednisolone in addition to the initial disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis reduces joint destruction and increases the remission rate: A two-year randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3360-3370.

- Wassenberg S, Rau R, Steinfeld P, Zeidler H. Very low-dose prednisolone in early rheumatoid arthritis retards radiographic progression over two years: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3371-3380.

- Malysheva OA, Wahle M, Wagner U, et al. Low-dose prednisolone in rheumatoid arthritis: Adverse effects of various disease modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:979-985.

- Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Luta G, Sokka T. Efficacy of prednisone 1-4 mg/day in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled withdrawal clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1715-1720.

- Todoerti M, Scire CA, Boffini N, Bugatti S, Montecucco C, Caporali R. Early disease control by low-dose prednisone comedication may affect the quality of remission in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1193:139-145.

- Buttgereit F, Mehta D, Kirwan J, Szechinski J, Boers M, Alten RE et al. Low-dose prednisone chronotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A randomised clinical trial (CAPRA-2). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013.72:204-210.

- Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Welsing PM, et al. Low-dose prednisone inclusion in a methotrexate-based, tight control strategy for early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:329-339.

- Saag KG, Criswell LA, Sems KM, Nettleman MD, Kolluri S. Low-dose corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis. A meta-analysis of their moderate-term effectiveness. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1818-1825.

- Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Meta-analysis of short-term low dose prednisolone versus placebo and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 1998;316:811-818.

- Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, et al. Low dose long-term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: An analysis of serious adverse events. Am J Med. 1994;96:115-123.

- Wei L, MacDonald TM, Walker BR. Taking glucocorticoids by prescription is associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:764-770.

- Laan RF, van Riel PL, van de Putte LB, van Erning LJ, van’t Hof MA, Lemmens JA. Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:963-968.

- Pincus T, Brooks RH, Callahan LF. Prediction of long-term mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis according to simple questionnaire and joint count measures. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:26-34.

- Sokka T, Pincus T. Ascendancy of weekly low-dose methotrexate in usual care of rheumatoid arthritis from 1980 to 2004 at two sites in Finland and the United States. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1543-1547.

- Pincus T, Castrejon I, Sokka T. Long-term prednisone in doses of less than 5 mg/day for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: Personal experience over 25 years. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011; 29(5 Suppl 68):S130-S138.

- Pincus T, Sokka T, Castrejón I, Cutolo M. Decline of mean initial prednisone dose from 10.3 to 3.6 mg/day to treat rheumatoid arthritis between 1980 and 2004 in one clinical setting, with long-term effectiveness of doses less than 5 mg/day. Arthritis Care Res. 2012; Nov 30. [Epub ahead of print]

- Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Bergman MJ, et al. RAPID3 on an MDHAQ is correlated significantly with activity levels of DAS28 and CDAI, but scored in 5 versus more than 90 seconds. Arthritis Care Res. 2010; 62:181-189.

- Pincus T, Yazici Y, Sokka T. Are excellent systematic reviews of clinical trials useful for patient care? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:294-295.

- Moses LE. The series of consecutive cases as a device for assessing outcomes of intervention. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:705-710.

- Wolfe F, Hawley DJ. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:245-252.

- Pincus T, Sokka T, Kautiainen H. Patients seen for standard rheumatoid arthritis care have significantly better articular, radiographic, laboratory, and functional status in 2000 than in 1985. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1009-1019.

- LaRochelle GE, Jr., LaRochelle AG, Ratner RE, Borenstein DG. Recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving low-dose prednisone. Am J Med. 1993; 95:258-264.

- Caplan L, Wolfe F, Russell AS, Michaud K. Corticosteroid use in rheumatoid arthritis: Prevalence, predictors, correlates, and outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:696-705.