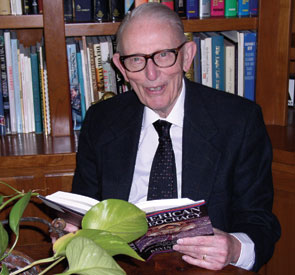

Maybe it’s the soft trace of a southern accent, or the respect he accords even ordinary questions. Whatever the clue, you quickly perceive that John T. Sharp, MD, is both a gracious and an authoritative person. Perhaps it is this disarming combination of qualities that most endears Dr. Sharp to his fellow rheumatologists, many of whom regard him as a giant in the field of RA—and not just because he created the Sharp score, a standardized outcome measure for tracking RA progression.

“I have known John for 15 years,” says Lee S. Simon, MD, associate clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston and former division director of the Arthritis, Analgesic, and Ophthalmologic Drug Product Division at the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “But, in those years, he has always been this unassuming, modest kind of guy with impeccable manners. He never interrupts anybody, he never pushes his theory in front of somebody else’s theory, and he allows people to talk. Even when there is an argument, he just continues to ‘plug away’ on the evidence, which he knows quite well.”

Vibeke Strand, MD, adjunct clinical professor of medicine in the Division of Immunology at Stanford University and a biopharmaceutical consultant who has worked with Dr. Sharp on numerous development programs on treatments for RA, agrees. “He’s very modest and unassuming, and he’s always bringing people together,” says Dr. Strand. “He’s a real delight, and it’s really a pleasure always to continue to learn from and work with him.”

Throughout his nearly six decade–long career, Dr. Sharp’s keen intelligence and passion for standardized outcome measures have led him on a path of discovery that some have called courageous. According to other top rheumatologists and drug researchers interviewed for this article, the last 15 years of pharmacologic advances in RA would not have been possible without a quantitative measure for evaluating disease progression—a measure made possible by Dr. Sharp’s seminal work in the 1960s and early 1970s.

How did the idea for such a method come about? And how did Dr. Sharp pioneer this method of quantitatively assessing erosions and joint space narrowing to measure progression of RA over time? During two recent afternoon conversations from his home on Bainbridge Island near Seattle, Dr. Sharp amiably agreed to talk about the influences on his career and the scoring technique he developed.

“I tell this story—and it’s almost true,” he begins wryly. “I sat down one afternoon and in a couple of hours designed the whole system. Of course, having designed it, it took six months, a year, maybe even a bit longer, to collect the data to show that it was an appropriate measure, and that it correlated with the features of clinical outcomes that were important.”

Throughout his nearly six decade–long career, Dr. Sharp’s keen intelligence and passion for standardized outcome measures have led him on a path of discovery that some have called courageous.

Of course, many events and influences led to that afternoon’s work, including Dr. Sharp’s reasons for entering the specialty in the first place.

Why Rheumatology?

As a young resident, Dr. Sharp had been fascinated with rheumatic fever. Realizing that he could not specialize in one disease, he began to consider cardiology, infectious disease, or rheumatology. Of the three specialties, he thought that rheumatology offered more challenges and began looking for a fellowship program.

Dr. Sharp was also clear about one thing: Rheumatology “was a good field for somebody who was interested mostly in investigation.” When he began his rheumatology fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1953, the standard treatments for RA were aspirin (often to the point of toxicity), extra rest, and physical therapy. “There was so little that could be done for patients,” he recalls. “But in terms of opportunities for studies, it was fairly wide open.”

After his residency, Dr. Sharp took a position at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Mich. The idea for an X-ray scoring system grew out of disagreements Dr. Sharp had with his colleagues there about whether gold was an appropriate treatment for RA. At the Massachusetts General Hospital, where he had trained, Walter Bauer, MD, and colleagues adamantly opposed gold therapy because of its serious toxicities. Dr. Sharp and his Ford Hospital colleagues were intrigued with a study in the early 1960s published by the British Empire Rheumatism Council showing symptomatic relief in patients given gold, but no benefit on the X-rays.

The rheumatologists at the Ford Hospital, including Dr. Sharp, felt that the study could be improved. The schedule of treatment in England differed from that at the Ford Hospital—stopping after a single course of injections, versus the American model of a loading dose followed by maintenance therapy. The team agreed that, to resolve the question, they should set up a two-year trial incorporating the latter schedule of treatments.

A Lone Voice

If the team at Ford was to conduct its own study, Dr. Sharp insisted that the study should include good radiographic analysis. So, he accepted the challenge to establish that part. The X-ray analysis in the Rheumatism Council study only examined whether the investigators saw anything worse. “My thinking,” recalls Dr. Sharp, “was that if you assigned a number that was a reasonable estimate of ‘how much worse,’ that it might be sensitive enough to pick up the changes that you couldn’t see otherwise.”

Joints in both feet and both hands were scored for erosions (from 0 to 5), and for joint space narrowing (from 0 to 4). Totals of all scores yielded the composite score.

The idea of using X-ray scoring was based on the realization that stored X-ray films were permanent records, says Dr. Sharp, who at the time had already instituted a routine of obtaining yearly hand X-rays of his patients. Swelling scores, in contrast, can differ from day to day, “and you can’t turn the patient back in time to check that score. But you can always get out the X-ray and review it.”

Patient accrual for the study was slow, and in the meantime, Dr. Sharp left Ford for Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Characteristically, he maintained good relationships with his former colleagues, and credits the efforts of Gilbert Bluhm, MD, a rheumatologist in Troy, Mich., in bringing the study to completion. The X-ray method was published in 1971 and the gold study in 1974.1,2 Modifications of the score followed almost immediately, explains Dr. Sharp, whose intent was to develop a method that was user-friendly for clinicians.

“At the time [that Dr. Sharp began his work], we were using improvement methodology that was archaic and mostly dependent upon patient report and very little that was validated,” notes Dr. Simon. “He was a lone voice out there suggesting that, in fact, we could do an objective measurement, that it could be done by a rheumatologist, and that it is reproducible, accurate, and can be monitored over the long term.”

Sharing the Wealth

Outcome measures in rheumatology have come a long way since the beginning of Dr. Sharp’s career, and much of that advancement, assert his colleagues, is due to his innovations. As a member of the steering committee of OMERACT, (Outcomes Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials), Dr. Simon has interacted often with Dr. Sharp, whose passion for standardized outcome measures continues to blossom.

“In 1999,” says Dr. Simon, “the work became legitimized when the FDA said that, for approval of a drug or a therapeutic for the treatment of structural progression in rheumatoid arthritis, the Sharp score was one of the acceptable methodologies. He stuck to his guns, and he then won—and he was correct. That’s a very important addition to the profiles of how evidence is accumulated in our field. And the work he’s doing now, which is to look at the question of measuring healing with this similar methodology, continues to be seminal.”

Since its initial development, the Sharp score has undergone many modifications, about which he is characteristically gracious. Desiree van der Heijde, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at University Hospital Maastricht in the Netherlands, first became aware of his work while doing her PhD thesis in 1986. Three years later, in 1989, she published her first modification of the Sharp Score, in which the erosion score for the MTP joints in the feet is doubled, to a total of 10.3 The hand erosion scores remain the same as in the original Sharp score, and joint subluxation is also included in the joint space narrowing score.

Great Man in the Field

Dr. van der Heijde recalls how excited she was, as a young researcher, to meet Dr. Sharp for the first time at the ACR. “Meeting him, as the great man in this field, was wonderful for me. He always wants to show his development of the score as just an ordinary thing which he has done,” she continues. “And he’s also very willing to share everything. He never keeps things for himself—he’s willing to share credits and new developments.”

Dr. Strand’s close affiliation with Dr. Sharp began in the mid-1990s, when she “pulled him out of retirement” to consult on the leflunomide program with the FDA—“for which his wife has never forgiven me!” she laughs.

Dr. Sharp came to the FDA “at least twice,” she remembers, to help teach assessment of radiographic damage and change. “I don’t think anyone else could have gone to the FDA and shown them how to read these films other than John, with his very unassuming manner.

“He’s been a wonderful man to work with,” says Dr. Strand. “He really has not only this panache, but clout. And he’s so modest.”

At one point, recalls Dr. Strand, Dr. Sharp tried to “un-name” the Sharp score. While co-writing with her a review paper published in Arthritis & Rheumatism, Dr. Sharp sent back a draft stating the score should simply be referred to as “a composite score” rather than the Total Sharp Score [or its modifications].4

Slowing Down—of a Sort

Now in his 80s, Dr. Sharp admits to a little slowing down, but one could hardly call his current activity level retired. Among other projects, Dr. Sharp has been an active co-chair of an OMERACT group that is working on developing computer-based methods of joint space measurement. “We were both deeply involved in the workshop on repair, and also in preparation of all the scoring for big projects,” says Dr. van der Heijde. “It’s still a pleasure to read [X-rays] with him and to hear his opinions.”

In addition to his work with OMERACT committees, Dr. Sharp continues to attend ACR meetings and has lively communications with researchers around the world. His time while at home in Bainbridge is also full: He and his wife walk, garden, read, and frequently spend time with a nearby son and grandchildren. Dr. Sharp also volunteers with a local Rotary Club and finds time for woodworking.

Asked to characterize his contributions to the field of rheumatology, Dr. Sharp appears reticent to paint his importance too broadly. He compares the method with a once-common attraction at country fairs, where you pay a fee to have someone guess your weight. Even if you win, the prize is worth less than the fee you already paid.

“The point I’m trying to make is that people get pretty good at making estimates like that,” says Dr. Sharp. “Those of us who’ve spent some time looking at X-rays get pretty good at estimating how bad the damage in a particular joint is. One thing that makes it much easier, in trials and in clinical practice, is comparing two or three films over time, looking for change.”

The Sharp score is very important for evaluating drug therapy, he notes. “Without a truly objective measure of what is happening to the joint structure, it would be very hard to understand to what extent a drug that makes patients feel better now is really doing something to their long-term health,” he says.

“This is the best we have right now—and as a matter of fact, I think it’s pretty good,” he says, adding, “I think scoring is a transient method. As soon as we have something that is really very efficient and very accurate, in terms of actual measurements, then people will say, ‘Why on earth did we ever bother with scoring?’ ”

It is this kind of understated authority that makes Dr. Sharp such a well-respected figure in the field. To a person, each of his colleagues had universally positive things to say about Dr. Sharp. Dr. Strand expressed it most succinctly: “I don’t think I’ve ever met such an elegant man.”

References

- Sharp JT, Lidsky MD, Collins LC, Moreland J. Methods of scoring the progression of radiologic changes in rheumatoid arthritis: correlation of radiologic, clinical and laboratory abnormalities. Arthritis Rheum. 1971;14:706-720.

- Sigler JW, Bluhm GB, Duncan H, Sharp JT, Ensign DC. Gold salts in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind study. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:21-26.

- Van der Heijde DM, van Riel PL, et al. Effects of hydroxychloroquinine and sulphasalazine on progression of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1989; 1:1036-1038.

- Strand V, Sharp JT. Radiographic data from recent randomized controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis: What have we learned? Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):21-34.

Career Timeline

- 1947

After serving as a student in uniform during World War II, Dr. Sharp graduates from the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. - 1949

Completes a two-year residency at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, where he works with Charles Ragan, MD, chief of Presbyterian Hospital’s arthritis program. - 1951

Completes a two-year residency at Dartmouth. - 1952

On a tour of duty in the Navy during the Korean War, during which he is stationed in New Hampshire and Maryland. - 1953

Begins rheumatology fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital, working in their pioneering academic program under Walter Bauer, MD. - 1960

Accepts a position at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Mich. - 1962

Becomes chief of rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, where he spends 15 years building a solid program. - 1976

Accepts a position as chief of medicine at a VA hospital with the hope of building a new medical school at Champagne/Urbana. VA budget cuts prevent this, however. - 1980

Moves to the Joe and Betty Alpert Arthritis Center in Denver. - 1986

At age 62, faced with a retirement he was not quite ready for, Dr. Sharp joins a small medical clinic in Tifton, Ga. - 2006

Now (mostly) retired, Dr. Sharp spends his days relaxing with his family and volunteering in his community when he is not working to develop new outcomes measures or collaborating with other rheumatology researchers.